Despite the best efforts of the international community, pirate attacks have continued unabated. Kenya’s relative stability and geostrategic location makes it a crucial actor to be involved in all aspects of counter-piracy in the region. How though, is this being articulated in Kenya’s foreign policy?

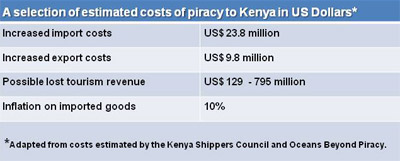

Globally, piracy poses a direct threat to the seascapes used to transport more than 80 per cent of all trade. According to a study by Oceans Beyond Piracy, the direct and indirect effects of piracy cost the world a staggering US$7 billion in 2011. As noted by United Nations (UN) Secretary General, Ban Ki-moon, piracy is also having a devastating effect on regional economies, especially countries such as Kenya, which borders Somalia – the home of the modern-day pirate.

Kenya’s foreign policy seeks to support its self-interest and ensure that its national security and potential for social and economic development is secure. Central to this approach is the protection of its economic interests and, as an extension thereof, protecting access to the sea and the important international trade routes that traverse the Indian Ocean. The close vicinity of the piracy precinct to Kenya’s borders, as well as the existence of pirate networks inside the country, poses various economic and security challenges to Kenya’s foreign policy.

Unfortunately, Kenya’s international and regional engagement on maritime piracy issues has not been particularly well rooted in its foreign policy agenda.

Most lacking in Kenya’s foreign engagement on the matter is undoubtedly the lack of a coherent domestic strategy on the piracy issue that encompasses the judicial, defence, onshore and offshore dimensions, and that is able to steer such engagement. This explains the relatively poor positioning of the piracy concern in the country’s foreign policy and the lack of a coordinated approach by government officials on the issue. Although a strategy is supposed to be discussed by parliament, it is not presently receiving the priority it deserves. The overarching feeling of local commentators is that a concrete outcome is unlikely until well after the next set of elections in the country, which are scheduled to take place later this year.

However, there are hopeful signs. Kenya initiated and hosted an international conference on piracy in the second week of February this year, to which it invited representatives from a range of countries with an interest in the Gulf of Aden. Jointly hosted with the UN, the conference discussed ways in which piracy on the East African coastline may be combated. According to the Second Counsellor for Political Affairs in the Foreign Ministry, Anthony Safari, the main purpose of the conference was ‘to formulate a strategy to fight piracy that has contributed to the escalating lawlessness in Somalia’. This event illustrates the rising importance Kenya attaches to the problem.

The formulation of a strategy on Somalia will certainly improve the possibilities for successful bilateral and multilateral initiatives, building also on the experience of past failures. For example, despite the best intentions, international agreements surrounding the prosecution of pirates in Kenya, which criminalises piracy, have failed. A lack of resources and expertise, and poor information surrounding procedural and evidentiary requirements in Kenyan law has posed a substantial challenge. This event arguably signals the country’s readiness for more strategic engagement with regional and international partners on the formulation and implementation of a robust anti-piracy strategy.

Additionally, Kenya’s willingness to use force in protecting its interests by way of its incursion into Somalia is noteworthy. While the move was not intended to act as an overt response to the Somali piracy problem, an ancillary outcome for Somali pirates is more restrictions on their freedom of movement and operation. This has supported foreign policy objectives, and illustrates that Kenya will act militarily to ensure its national security.

Additionally, Kenya’s willingness to use force in protecting its interests by way of its incursion into Somalia is noteworthy. While the move was not intended to act as an overt response to the Somali piracy problem, an ancillary outcome for Somali pirates is more restrictions on their freedom of movement and operation. This has supported foreign policy objectives, and illustrates that Kenya will act militarily to ensure its national security.

In going forward Kenya needs to ramp up and streamline its piracy-relevant activities in alignment with a comprehensive and robust strategy that addresses the piracy problem and engages key actors present in the Gulf of Aden, as well as international organisations such as the UN. From a regional perspective, greater involvement in initiatives such as the tripartite anti-piracy memorandum of understanding between South Africa, Mozambique and Tanzania would be useful. This has emerged as an extension of a pre-emptive bilateral naval arrangement between South Africa and Mozambique, in response to the fear that the piracy threat may move southwards into the Mozambique Channel. In addition, more robust Kenyan engagement on regional arrangements such as streamlining the legal framework on anti-piracy activities, conducting joint patrolling, and devising avenues for supranational prosecution are also essential.

In sum, successful Kenyan engagement on piracy should be rooted in a comprehensive strategy that supports a cooperative approach with domestic, regional and international actors.