The protests turned violent following efforts by the police to restrain the march. Nineteen people were killed in the three main towns of Mzuzu, Lilongwe and Blantyre. Some shops were looted and cars, including those of privately-owned radio stations, were scorched.

These events caught the attention of the world and questions were raised about what had sparked such a response from the Malawian people who are well-known for being among the friendliest on the African continent. Differing views have been expressed by those in Malawi and commentators on the outside as well. This article attempts to provide an independent analysis based on the views of these commentators as well as information sourced from analysts in Malawi.

There is no doubt that Malawi is a country in economic crisis. This is despite a number of recent successes in addressing food security concerns and an average of seven per cent growth in the past five years. This rapid growth was largely driven by the financial window provided through debt relief by donors in 2005. In 2006, debt relief accounted for 70 per cent of GDP. In reaction to a severe food shortage in 2005, the government invested a large portion of these funds in a fertilizer subsidy programme. In addition, urban Malawians have taken advantage of expansionary fiscal policy and the vast aid inflows – on average 20 per cent of GDP per year – to improve their standard of living.

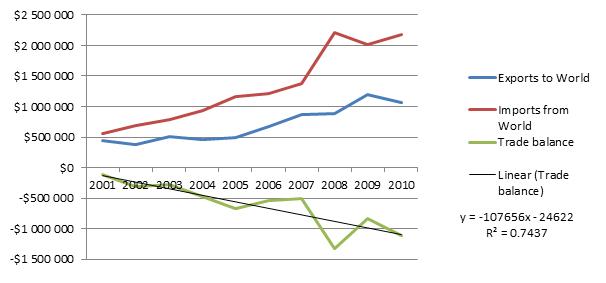

In terms of expenditure, debt relief and current aid largely feed into consumption and, barring health and road infrastructure, not into a concerted effort to improve Malawi’s productive capacity. This has led to an increase in the trade deficit to 21 per cent of GDP in 2010, up from seven per cent in 2001. In 2010, Malawi’s imports totalled 41 per cent of GDP, compared to exports worth only 20 per cent of GDP. Malawi’s trade balance is presented in Figure 1 below and there is a clearly evident negative trend, starting in 2001.

Figure 1: Dollar amounts in thousands. Source: International Trade Centre’s Trademap.org

The results of such policies are not unknown in Southern Africa. History provides examples of the strain on an economy that an unrealistic exchange rate can bring to bear. It results in large foreign exchange shortages and development of a vibrant informal market for foreign exchange which brings with it additional challenges from increased corruption and illegal activities. Those who suffer most are in the formal business sector, and specifically exporters.

In Malawi, the shortage has further reduced the ability to export because Malawian firms cannot purchase the foreign exchange they need to finance their inputs. This has increased the required levels of working capital and storage expenditure. Malawi’s woes have been exacerbated by regular electricity cuts, by the government’s attempt to reduce its dependence on donor aid, which in 2009/2010 accounted for 40 per cent of budget expenditure and by a disappointing tobacco season. Tobacco accounted for 55 per cent of exports in 2010 and this year 75 per cent of the harvested leaf currently remains unsold as of mid-July. Tobacco sales started in March.

In Malawi, the shortage has further reduced the ability to export because Malawian firms cannot purchase the foreign exchange they need to finance their inputs. This has increased the required levels of working capital and storage expenditure. Malawi’s woes have been exacerbated by regular electricity cuts, by the government’s attempt to reduce its dependence on donor aid, which in 2009/2010 accounted for 40 per cent of budget expenditure and by a disappointing tobacco season. Tobacco accounted for 55 per cent of exports in 2010 and this year 75 per cent of the harvested leaf currently remains unsold as of mid-July. Tobacco sales started in March.

It is the grassroots impact of these high level economic decisions that is the most important to understand if we are to analysis the protests in Malawi. We recently spoke to a citizen of Malawi while he was queuing at a petrol station waiting for a delivery. He said that in 2005 the queues in the country were at maize storage facilities where people waited for food. Now the lines are at petrol stations. The government of Malawi might argue that this is progress but the reality is that Malawi has not invested its debt relief and new aid in developing the human capacity required to drive the competitiveness of its economy. As a result it is now struggling to afford the fertilizer subsidy and improved urban standards of living.

The demonstrations in Malawi are a symptom of an economy that experienced growth without sufficient investment in addressing supply-side constraints and developing a favourable business environment. Such investment is paramount for Malawi to be able reach a position in which it can afford, on its own account, to finance the programmes which protect against food shortages faced by the 70 per cent of Malawians who live on less than$1.25 a day. It is also necessary if these and other poor Malawians are to actively contribute to Malawi’s development effort through access to education and employment.