In the face of rising impunity and violence, increasing abuses of power, commodity price hikes, power failures and the rising fatalism of society in general and the youth in particular, a small group of young men have committed themselves to the restoration of a civic political culture and an accountable government. Africa is demographically the youngest continent. According to the African Union, about 65% of the total population of Africa are below the age of 35 years, and over 35% are between the ages of 15 and 35. By 2020, it is projected that out of 4 people, 3 will be on average 20 years old. This new generation largely consists of what South Africans refer to as the “born frees”, or those who have not experienced the direct consequences of colonialism and autocracy. In South Africa and across the continent, it is increasingly apparent that this new generation is largely averse to politics: fewer young people vote or participate meaningfully in politics. A recent study published by the Afrobarometer suggests that African youths are thirteen percent less likely to vote than their older counterparts.

Each year, about 10 million new young people enter the labour market. This occurs in a context of unstable markets, reductions in aid, trade and investment and slowing global economic growth. We see greater inequality in Africa than almost ever before. Youth face the daunting related challenges of unemployment, underemployment, a lack of skills, a lack of access to a relevant education, and little access to health-related information and services including those related to the diagnosis, treatment, and care of those living with HIV. In South Africa, these trends have led to the strange duality that a more militant youth is emerging and is demanding greater access to these goods while they largely avoid formal political engagement.

In response to similar trends which had emerged in Senegal alongside an increasingly authoritarian and corrupt government presided over by Abdoulaye Wade, a small group of young men decided to mobilise and engage the youth to revitalise Senegalese democracy. They built their campaign on a strong sense of national pride and civic awareness. Their movement was launched in January 2011 and became known as Y’en A Marre, a Wolof phrase translated as “we are fed up” or “enough is enough.” The core group consisted of a hip-hop duo from the band “Keur Gui of Kaolack” and a number of journalists, all of whom decided that change was urgently needed in Senegal.

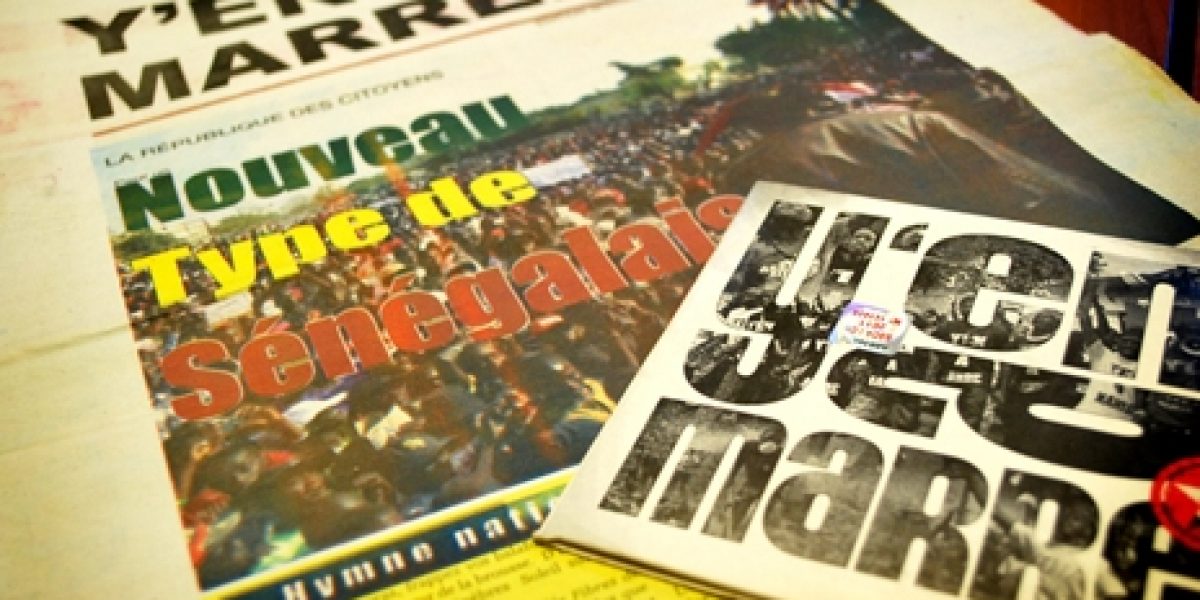

Y’en A Marre became the beginning of deeper thinking and greater engagement of the youth in politics, the movement became the mouthpiece of disaffected young people ahead of the 2012 elections. Faced with a lack of funds, the group decided to do what they knew best, produce music. They created a number of songs in both French and Wolof and used these to reach young people and spread the message that the government needed to work for the people of Senegal.

Their best-known song, “Abdoulaye Faux! Pas Forcé” or “Abdoulaye, don’t force it, give up!” became a rallying cry for all those opposed to Wade’s third term and received more than 70 000 hits on YouTube; impressive for a country in which only approximately 16% of the population have internet access. The movement used door-to-door campaigning, concerts in schools and outdoor rallies to mobilise citizens, and successfully registered over 600 000 youths on the country’s electoral roll.

Their music generated a huge response, and to raise further funding they sold their CD and T-shirts with the phrases “Y’en A Marre” and “Je Suis un Nouveau Type de Senegalais (NTS)”, or “we want a new type of Senegalese.” The shirts became a call-to-arms for young and old alike, a calling card for change. Walking through the streets of Dakar three months after the March run-off election which saw Abdoulaye Wade unceremoniously removed from power, Senegalese people stop to smile and speak to me in my “Y’en A Marre” shirt, discussing the movement with enthusiasm and pride.

The group faced the wrath of Wade’s state, with their gatherings dispersed by teargas and facing arrests by the police. These youths were harassed and intimidated, but would not back down or resort to violence. The movement also stubbornly refused to align themselves to a particular political party or candidate, arguing instead that they would act outside of formal political parties to call for thoroughgoing change in Senegalese society. Following his win at the polls, Mack Sall’s administration offered these indigent young men – in their scruffy clothes, caps and sneakers – important government posts. They declined the offer; instead the movement opted to stay out of politics, to act as a sentinel of Senegalese democracy, to motivate the people and continue to hold the government to account.

The booming young generation of Africa could learn much from this movement. Essentially the lesson revolves around ownership and the desire to play an active and positive role in the future of one’s community and country. In the wake of their successful campaign to unseat Wade, Y’en A Marre has committed to work both beside and independent of the state to undertake community development initiatives to change urban culture, clean up urban spaces, combat coastal erosion, fight the HIV/Aids pandemic through community health projects and try to encourage peace and social mediation in the conflict-prone Casamance region. Finally, they are calling for a pan-African youth movement to engender change on the continent.

This movement should serve as an inspiration and an example to youths of other African states, to take ownership of the political space and thus of their own futures. It is important to remember that democracy is not an end but a constant process, its protection must be ensured through political participation and constructive social action. As the young men of Y’en A Marre can attest, those who fall asleep in freedom may well wake up in slavery.

This article was written as a result of a conference in Dakar in June 2012 held by the West African Research Centre (WARC) in collaboration with the Institute for Defense Analysis (IDA). The author would like to thank the convenors and attendees for the contributions that discussions made to this article.