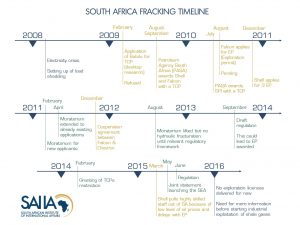

However, the departments of Environmental Affairs, Water and Sanitation, Energy, Mineral Resources and Science and Technology have issued a joint statement launching a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) for Shale Gas Development. This SEA establishes a project team which will undertake a two-year study on the possible implications of fracking on a large number of issues – from environmental to economic, including spatial planning, human health and heritage concerns. The SEA emphasises the need for further information before the start of industrial fracking in South Africa.

This statement could be seen as another delay for applicant companies in their quest for the exploitation of the Karoo’s potential shale gas resources. Companies including Shell, Falcon and Sasol have been wait-ing since 2010 to get an exploration permit which would allow them to undertake field surveys. Indeed, even if the regulation around fracking could lead to the issuing of exploration permits, an industrial process should fortunately not start before the end of the investigation into the impact of fracking in the Karoo.

The sluggish application process reflects the myriad and valid concerns related to fracking.

There is a credible risk that fracking can lead to water contamination. Fracking is also thought to be responsible for air pollution and contributing to global warming through the leakage of methane gas into the atmosphere. Moreover, the process is criticised for the huge quantities of water used. The use of the collected gas also remains a critical point: ultimately, the gas is burned, emitting greenhouse gases (GHGs) into the atmosphere and exacerbating climate change conditions.

Nevertheless, the use of shale gas is commonly couched as a transition to a greener future. Half the amount of CO2 is released in the production of one MW of electricity by burning shale gas compared to the use of coal in the same. However, coal remains the primary source of electricity generation in South Africa and it is important to remember that while appearing to be less harmful than coal, shale gas still releases significantly more GHGs than other energy sources such as solar, nuclear, hydro or wind.

These concerns have motivated some countries to restrict fracking. For example, in France fracking has been prohibited since 2011 by virtue of a decision taken by the French parliament. However, in the US, fracking has been in operation for sixty years which lead to significantly less dependence on other countries for its fossil fuel needs. Indeed, in recent years, an increase in domestic gas production in the US has enabled the country to reduce its gas imports considerably.

The exploitation of shale gas could also support job creation, an increase in the country’s gross domestic product, economic growth and potential socio-economic benefits. Nevertheless, in the case of South Africa, these anticipated outcomes may have to be reevaluated because of the uncertainty around the actual deposits of shale gas in the Karoo.

Indeed, the size of the deposit appears to be the biggest issue in the shale gas debate and the anticipated socio-economic benefits are entirely dependent on its size. If the deposit is very large, it could lead to an exploitation of several years, generating significant employment and useable gas. On the contrary, if it is small, positive spillovers could be limited.

Other important concerns that are unique to South Africa must also be emphasised. One of these is the potential for competition over scarce water sources between cities, farms and fracking companies in the drier areas of the Karoo. Another important consideration is the presence of dolerite dykes in the area. This is the first occurrence of these geological structures where the exploitation of shale gas is planned. This could lead to further problems which are not yet clearly measurable.

The question of fracking is therefore complex. Shale gas is seen by many as a way to start a transition to a greener future, offering a route to produce electricity with a smaller carbon footprint. The process is also viewed as a solution to increase South Africa’s electricity generation capacity in view of the current power crisis.

However, informed by my home county’s decision on the prohibition of the exploitation of shale gas in France, fracking is not a progressive solution given the current climate debate and the concerns around the environmental impact on the fragile ecosystem of the Karoo. While a decision favouring fracking would require the development of new skills and technologies, it would also take attention away from developing new competences related to renewable and sustainable energy sources, instead entrenching a reliance on fossil fuels.

Before arriving at a final decision on fracking, the size of the deposit needs confirmation. As emphasised in the joint statement which resulted in the launch of the SEA, as well as other research in this field, more information and research are required before South Africa takes the route towards the exploitation of shale gas for industrial use. Importantly, fracking should not be considered as an immediate solution to solve South Africa’s current and urgent electricity crisis.

Given the number of concerns to be addressed by the project team for the SEA, sufficient time should be spent on obtaining the relevant information. It is also important to remember that developing a new industry around shale gas is not a sustainable alternative to the production of electricity through coal. Moreover, while skills development in fracking would be essential, it would appear more prudent to develop green skills instead of fossil ones.