While her election in July 2012 was a source of division among African Union (AU) member states, her reputation as a capable leader signalled a new dawn for the AU. South Africa, which sponsored her candidacy to the chagrin of key regional powers, including Nigeria, used her competencies to articulate implicit weaknesses in the AUC, while mobilising for high expectations regarding the future of the AU.

However, just like her contested entry as Chairperson, her first year in office has yielded mixed results, with the AU still unable to turn into an effective continental and global actor, able to deal with the myriad challenges facing Africa. Granted, a year is hardly a sufficient timeframe to make a judgement on her contribution to regional integration. Nonetheless, given that she has a four-year term at the helm of the AUC, it is opportune to assess her progress so far.

Astute management of the continental agenda

Under Dlamini-Zuma, the AU celebrated its golden jubilee at an extraordinary summit in May 2013, under the theme of ‘Pan-Africanism and African Renaissance’. Notwithstanding a few technical and administrative hiccups, the Commission under her guidance has been credited with organising exemplary summits. Events start on time with better agenda management for leaders who in the past spoke far beyond allocated times. She has also been gracious enough to highlight shortcomings when things did not go smoothly.

The method and style of Dlamini-Zuma, and her insistence on efficient use of scarce resources, including better interdepartmental cooperation and coordination, seem to have created a new sense of purpose within the Commission. Officials have adapted to her method and have supposedly bought into the administrative strategy and vision she has set for the AUC.

More importantly, the AU launched under her watch a bolder and more ambitious discussion for the next 50 years. Continental consultations with various stakeholders have started, and a website dedicated entirely to this exercise was launched on 3 September 2013. It is expected that the conclusive Agenda 2063 document will be considered by the AU policy organs in January 2014, with a final presentation envisaged for June 2014.

Dlamini-Zuma has also dealt deftly with the potentially contentious item on international jurisdiction, justice and the International Criminal Court, which triggered the Extraordinary Assembly on 12 October 2013. An African withdrawal from the Rome Statute has been averted for the moment. These are skillful and laudable initiatives, which are instilling a new sense of urgency and attention to potentially divisive issues in continental governance.

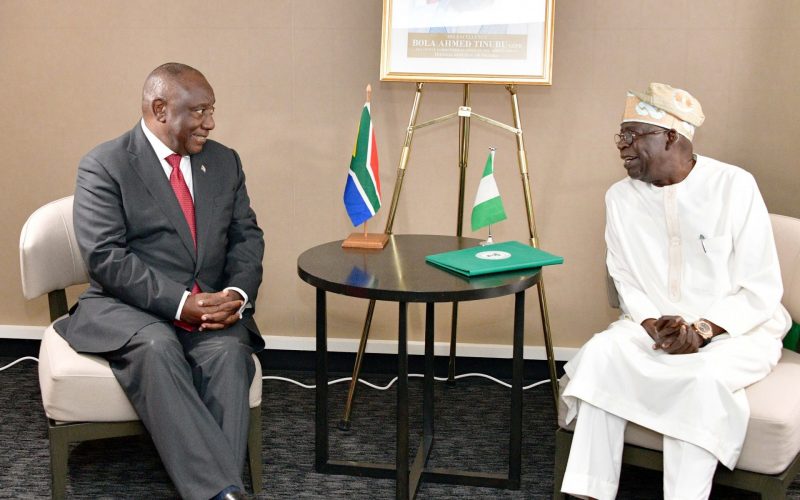

With the backing of Pretoria, and as a former foreign minister of the most powerful economy on the continent, South Africa, she has been able to profile the AU as a better and more visible diplomatic actor in international affairs. She has provoked stronger political engagement in the affairs of the AUC. Barely a year in office, she has set her mark on the global diplomatic scene having met with key global leaders, including President Barack Obama of the United States, François Hollande of France and Dilma Rousseff of Brazil. That she travelled to Pretoria in June 2013 to meet with President Obama is indicative of her closeness to South African foreign policy objectives, including how the relationship can be effectively used to the advantage of the African Union.

Dealing with old and new challenges

Notwithstanding a higher profile for the AU and the strengthening of the AUC’s institutional mechanisms, Dlamini-Zuma’s year in office has been marked by certain old and new challenges. First, while Dlamini-Zuma vowed in her acceptance speech last year that the AU would prioritise the conflict in Mali and in the Sahel, the AU was completely out of its depth in that region. With the AU unable to take rapid action that would have rendered French intervention in Mali possibly irrelevant, the limits of ‘African solutions to African problems’ became more pronounced.

Second, a coup d’état in the Central African Republic took place in April 2013, for which the body could not provide substantive solutions, with instability still plaguing that country. While Dlamini-Zuma has worked hard to put in place a continental peacekeeping force in that country, France has indicated that it would strengthen its presence there. The legitimisation of Michel Djotodia as interim head of state by the Economic Community of West African States cast aspersions on the AU’s Article 30, which does not recognise the unconstitutional overthrow of governments. It is unfortunate that there is not greater internal cohesion on matters of principle between Africa’s various regional institutions – this has been an enduring concern for successive AUC chairs.

Third, how she deals with the ICC question and the potential withdrawal of certain African countries from the Rome Statute remains a huge challenge.

Fourth, Dlamini-Zuma is widely credited with having turned the Commission into a much more efficient body, able to respond to some of the pressing challenges facing the continent. However, her senior appointments, consisting mainly of South African diplomats on secondment from South Africa’s Department of International Relations and Cooperation, seem to have created tensions within the higher echelons of the Commission. To compound the unease within the AUC, their powers and field of action seem to be extensive to the point where they interfere with the work of AU Commissioners who serve at the behest of member states.

Fifth, Dlamini-Zuma is still a member of the national executive committee of the ruling African National Congress in South Africa. Her continued involvement in national politics does not only result in regular visits to South Africa, which some may see as detracting her from AU activities, but it also raises questions about her longer-term appetite for the continental body in Addis Ababa. Dlamini-Zuma will certainly have to work hard to instill confidence in the capacity and ability of the AU to be a credible political actor on the continent, regardless of the nature of the crisis or challenge.

Africa continues to face immense challenges, including structural underdevelopment and dependency; huge backlogs in infrastructure, lack of basic services and human resource development and the need to build people-centred, inclusive and developmental public institutions.

Regional Economic Communities are important building blocks in dealing with these challenges. However, they operate to varying degrees of efficiency and have not been given solid institutional recognition at the AUC, functioning merely as liaison offices to the AU. Worse, they are understaffed and this begs the question as to whether they can serve as effective platforms for regional policy-entrepreneurship and coordination at the Commission.

The AU has the necessary continental frameworks, policies and strategies in virtually every area of critical importance to African development. Dlamini-Zuma did not start on a clean slate with the organisation drawing on lessons from fifty years of experience. However, states in Africa are still weak and state-centric impulses drive development. It therefore remains to be seen if Dlamini-Zuma could help position the African Union as the platform of choice to drive developmental processes on the continent.

As noted earlier, a year in office is still very short to make an assessment. However, it should serve as a moment for reflection and an opportunity to change direction or adapt where necessary. Going forward, navigating through the myriad challenges deftly and competently and the ability to bring on board key constituencies of the AU will determine whether Dlamini-Zuma will succeed during her tenure as Chairperson of the Commission.