The review mechanism was established in 2003, soon after the Organisation of African Unity became the African Union (AU). It was inspired by the desire to find “African solutions to African problems”. It was supposed to signify a new approach to politics in Africa: a voluntary, non-adversarial peer-review which would lead to improvements in governance.

States that are party to the peer review mechanism develop self-assessment reports, which are then combined with reviews produced by experts from other African countries. The reviews are then tabled and discussed by heads of state of member countries. Finally, the reviewed country embarks on implementing its national programme of action to address any governance shortcomings that were identified.

These are not just government reviews: they focus on the country as a whole. Civil society and the private sector are involved in putting together the national self-assessment. Reviews are supposed to take place every three to five years, but in practice only a handful of countries have been reviewed twice.

The mechanism got off to a good start. But enthusiasm soon waned. Between 2008 and 2016 the peer review mechanism’s secretariat did not have a permanent CEO, hardly conducted any reviews and was marred by allegations of financial mismanagement.

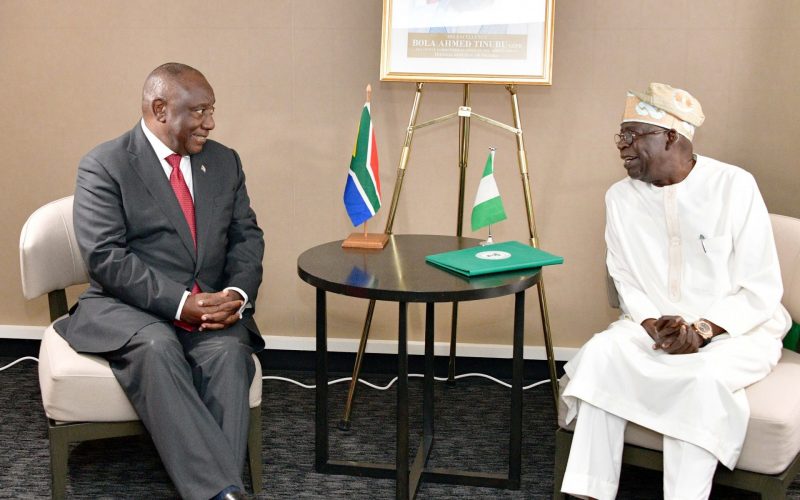

Three years ago the political stewardship of Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta, and the appointment of South African Professor Eddy Maloka as CEO of the secretariat brought new energy to the review mechanism. More countries joined.

Maloka implemented the “Three Rs Strategy”: restoration, reinvigoration and renewal. This helped, for the most part, to restore faith in the review mechanism and put it in a much stronger position. But political and technical challenges remain.

Country reviews have once again stalled and review reports aren’t being released on time.

The decline

The peer review mechanism works as a voluntary partnership between government, civil society, and the private sector. The aim is to collectively and collaboratively address socio-economic problems, improve governance practices and strengthen laws and policies. The key philosophy behind the initiatives is that, by working together, different stakeholders can achieve improved transparency, greater accountability and good governance.

The first decade saw 17 mostly solid, comprehensive and honest review reports being published. However, even then most enthusiastic member countries failed to implement their recommendations.

At the same time, attendance of the peer review mechanism’s annual forums, which were held on the sidelines of African Union summits, dwindled. Most heads of state delegated authority to ministers, who don’t have the same political clout.

What was supposed to be a frank discussion between African leaders about governance problems devolved into a mostly technical exercise, sprinkled with words of praise – but never criticism – from the few attending presidents.

Things went from bad to worse when not a single state was reviewed between 2013 and 2016.

Some progress but still problems

The situation has improved significantly since then. Reviews are resuming, and some countries are undergoing second reviews. These are intended to be pithier, specifically focusing on cross-cutting issues emanating from the countries’ first reviews.

And new members are joining, among them Namibia in 2017 and Botswana in February 2019.

As part of reforms introduced by Rwandan President and former African Union chair Paul Kagame in 2018, the review mechanism was incorporated into the continental body as a specialised agency, and given an expanded mandate.

Apart from conducting country reviews, it will now also track progress achieved under the African Union’s Agenda 2063 and the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. It will do this for the 38 members as well as countries on the continent that aren’t African Union members.

But there are still questions about whether African leaders have the will to make the peer review mechanism a strong initiative that can change the continental governance landscape. Its recently launched African Governance Report is a case in point. Although it provides trends and data on governance on the continent, it doesn’t mention any countries by name. This shows an unwillingness to “name and shame” those that lag behind in implementing progressive policies and ratifying treaties.

It’s also a missed opportunity to commend countries which are leading in promoting good governance, transparency and accountability.

The attendance of peer review mechanism forum meetings by top officials surged briefly under Kenyatta and Maloka, but quickly dissipated. Only four heads of state attended the recent meeting in February. Even more worrying is the failure to release available country reports. These are supposed to be published six months after they are tabled at the forum.

The Senegal review is now two years late, while Sudan and Uganda’s second reviews are over a year late. Chad and Djibouti’s 2017 reports have been released, but are only available in French. Insiders suggest that politicians are reluctant to make the information – which provides a balanced overview of governance in the country, including both strengths and weaknesses – available to their citizens.

The African Peer Review Mechanism must follow its own rules, and not be complicit with governments in burying these reports.

Going forward

The review mechanism should build on its current momentum to strengthen its status within the African Union. It should be able to release the review reports without waiting for politicians’ approval. It should also name member states that are not progressing or are not paying their annual financial contributions.

It also needs to modernise its website and make all documents, reports and press releases easily accessible. It is currently easier to conduct a Google search and find this information from other sources.

Finally, the review mechanism would benefit from establishing a civil society desk at its secretariat. Civil society is an important stakeholder and stronger links should be built for relationships that promote synergy in improving African governance.