Executive summary

However, the wrangling about coal energy – and the emerging split between China’s domestic and international coal expansion – obscures the role of recipient governments in mitigating the worst impacts of coal electricity. This policy briefing compares two Chinese-funded and -built coal electricity projects in Indonesia and Zimbabwe. It shows that the quality of implementation depends a lot on the local regulatory environment. Whereas Indonesia has managed to limit the environmental impacts of coal electricity to some extent, the same is not true for Zimbabwe. At the same time, the fact that these plants are embedded in regional coal economies presents its own challenges to environmental, socio-economic and governance (ESG) mitigation measures.

Introduction

Compared to the other sectors featured in this series of policy briefings, coal-fired electricity has seen the most rapid changes during the research period. President Xi Jinping’s announcement that China would stop building these plants overseas signalled a major policy change.1“China Pledges to Stop Building New Coal Energy Plants Abroad”, BBC News, September 22, 2021. However, China’s insistence on weakening the language on the phasing-out of coal at the COP26 climate-change summit in November 2021 underscored the centrality of the fuel in many Global South economies. It also made it clear that the debate about ESG mitigation of Chinese-driven coal projects domestically and along the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is far from over.2Leslie Hook, Camilla Hodgson and Jim Pickard, “COP26 Agrees New Climate Rules but India and China Weaken Coal Pledge”, Financial Times, November 14, 2021.

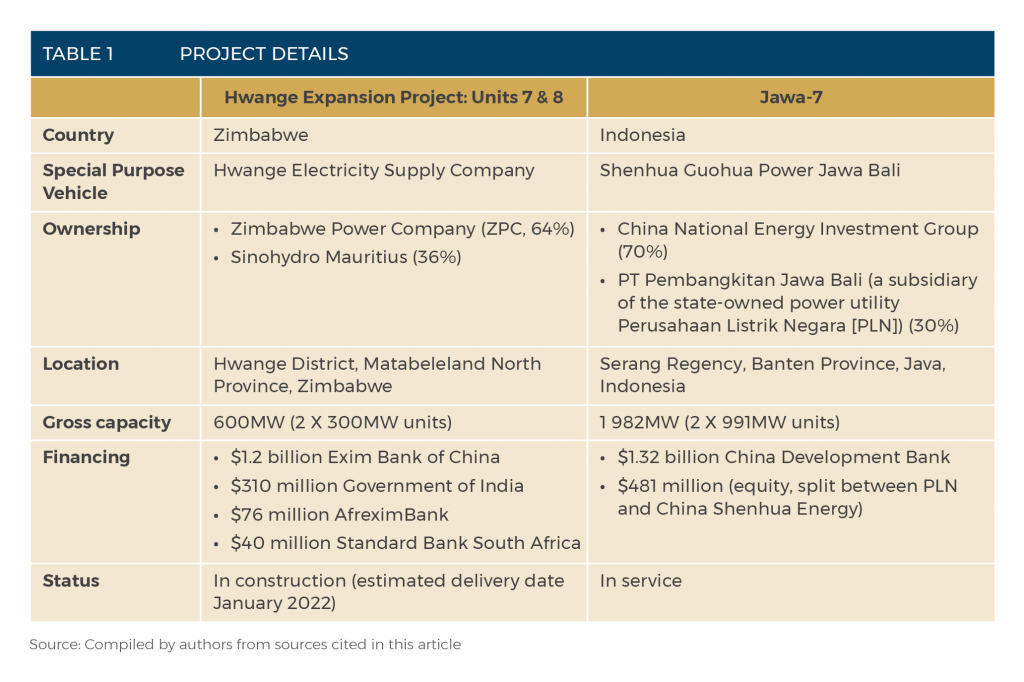

This policy briefing examines the issue of standard-setting as it affects ESG mitigation in Chinese coal-power infrastructure provision in the Global South. It focuses on two projects. The Hwange Expansion Project will see the addition of two additional units to an existing, colonial-era power plant in Zimbabwe. This project draws coal and water from the immediate area and is enmeshed in a network of related industries, including a colliery and a coking factory. Jawa-7 is the largest of several Chinese-financed coal plants in Indonesia, driven by the commitment by President Joko Widodo to implement 35 000MW of electricity capacity across the country’s many islands.3“PLN Targets to Complete 20 Percent of 35,000 MW Project This Year”, Jakarta Post, January 29, 2019.

ESG impacts: Jawa-7, Indonesia

Environmental

The Jawa-7 project has been promoted as the future of so-called clean coal technology. It limits harmful emissions through the use of ultra-supercritical turbines, which improve efficiency by 15%, and a proprietary seawater desulphurisation technique that optimises coal use and limits emissions.4Ronna Nirmala, “Activists Question Indonesia’s Commitment to Clean Energy”, Benar News, January 24, 2020; Hong Kong Trade Development Council, “Belt and Road Takes Indonesia Closer to Electrification Goal”, February 19, 2020.

The project has also been characterised as not only limiting environmental damage but, in fact, actively improving environmental outputs. For example, China Shenhua claims that, during the construction period, local mangrove-forest coverage increased by more than 30%, and that the design and planning of the project adopted a greater level of environmental protection than the Indonesian national standard.5State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “China Shenhua Contributes to Indonesia’s Largest-Capacity Thermal Power Project”, December 19, 2019. It should be noted, however, that national standards have been criticised as lax. About 60% of Jakarta residents are said to suffer from respiratory ailments due to air pollution.6Lauri Myllyvirta et al., Transboundary Air Pollution in the Jakarta, Banten, and West Java Provinces, Report (Helsinki: Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, August 2020). Research by Greenpeace Southeast Asia and Harvard University estimate that existing coal-fired power plants in Indonesia cause 7 100 premature deaths every year.7Greenpeace Southeast Asia, “Research from Harvard Reveals Health Impacts from Indonesia’s Coal Plants”, Press Release, August 12, 2015.

The project’s impact should be seen in the larger context of Indonesia’s resistance to addressing its coal dependence. The National Energy Policy and the Mid-term National Development Plan both envision a massive expansion in Indonesia’s coal-fired electricity generation capacity, sending strong signals about future growth in domestic demand for coal. Although Indonesia’s Nationally Determined Contribution commits to decreasing greenhouse-gas emissions by tackling deforestation and promoting renewable energy, it does not mention coal and the massive planned build-out of coal-generation capacity.8Aaron Atteridge, May Thazin Aung and Agus Nugroho, “Contemporary Coal Dynamics in Indonesia” (Working Paper 2018-04, Stockholm Environment Institute, Stockholm, 2018). This is despite the government’s setting a cap on overall coal production rates in its Midterm National Development Plan for 2014–2019,9Atteridge, Aung and Nugroho, “Contemporary Coal Dynamics”. and aiming to increase renewable energy to 23% of its total use by 2025.10Nirmala, “Activists Question Indonesia’s”. Despite Jawa 7’s claims to cutting-edge emissions technology, it still raises questions about Indonesia’s commitment to renewable energy sources.

Socio-economic

Shenhua emphasises its contribution to human resource development. About 180 employees were sent to China for training, while ‘apprenticeship training’ was set up in Indonesia with experienced Chinese technicians guiding their Indonesian counterparts. The company also invested an estimated $227,00011RMB 1.45 million at the time to cooperate with Indonesian universities to build a Power Simulation and Research and Education Cooperation Centre to boost training in the power sector.12China Shenua Energy Company Ltd, 2020 Environmental, Social and Governance Report, 2020, 15.

The company highlights its wider corporate social responsibility. For example, it provided clean drinking water to surrounding villages during dry seasons, and built roads, wells and mosques. It also claims to have provided over 7 000 local jobs. However, 2018 saw several protests from local workers alleging that the company was bringing in Chinese workers to replace locals.13TitikNOL, “Local Workers Call for the Prosecution of Chinese Workers Accused of Beatings”, September 9, 2018.

On labour rights protection, the company professes to observe national laws and regulation and carry out irregular inspections to ensure legal employment. It emphasises its support for international regulations and principles on human rights, labour rights, and so forth.14China Shenhua, 2020 Environmental, Social and Governance, 82.

Governance

The Jawa 7 project was a key BRI project, and enjoys high-level political will.15Nirmala, “Activists Question Indonesia’s”.

However, transparency and governance issues have brought some controversy to the project. Indonesian politicians retain great financial interests in coal-fired power plants, and local political influence is aided by the decentralisation of decision-making in the Indonesian system. Such decentralisation has generated a raft of incentive structures for local politicians to issue new permits to deliberately stimulate regional development.16Atteridge, Aung and Nugroho, “Contemporary Coal Dynamics”. Along with the lax policy environment, observers also are worried about the corruption in these activities, which leads local and national bureaucracies to support financing for coalfired power plants.17Atteridge, Aung and Nugroho, “Contemporary Coal Dynamics”.

Specific details about the project remain scarce. While general information (for example, basic loan and ESG information and that it was a greenfield investment) is known, transparency falls far short of the standards demanded by multilateral institutions such as the (Chinese-led) Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. These lapses were already flagged during the tender process.

In February 2016 the Indonesian House of Representatives created a special committee to investigate the process after finding that the winning consortium had initially been eliminated in the early stages of the process for not submitting estimates for engineering, procurement and construction costs. Indonesia’s anti-monopoly agency, the Business Competition Supervisory Commission, also investigated the tender. During the process, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources claimed that the central government had never issued permits for reclamation projects in the area, while the developers had already started working.18Retno Ayuningtyas, “Uncertainty Surrounds Jawa 7 Power Project”, Jakarta Globe, April 27, 2016. The project also raised eyebrows by reaching financial closing very quickly after the power purchase agreement was signed – much faster than the Japanese-backed Tanjung Jati B project, despite the fact that some of the stakeholders (for example Sumitomo Corporation) have a proven record of developing large-scale projects in Indonesia.19James Guild, “The State, Infrastructure and Economic Growth in Jokowi‘s First Term” (PhD diss., Nanyang Technological University, 2019), 201.

ESG impacts: Hwange Expansion Project, Zimbabwe

Environmental

Despite the Hwange Expansion Project’s centrality to Zimbabwe’s energy plans, no comprehensive environmental impact assessment is publicly available. Instead, researchers are forced to rely on patchy and outdated government reports on various other parts of the coal supply chain in the Hwange area, and highly critical reports by civil society groups and journalists about the current expansion and related projects. The effect is a low-information and low-trust environment, in which there are strong perceptions of collusion between regulators and project stakeholders with little say given to local communities.

What does become clear is that the environmental impact of the Hwange Expansion Project cannot be separated from the wider local coal economy within which it is

enmeshed and which will feed units 7 and 8 once they are operational.

For example, one of the most comprehensive impact reports publicly available is by the non-governmental organisation (NGO) the Centre for Natural Resource Governance (CNRG).20John Paul Moyo, Environmental Impact Assessment Report for Hwange Coal Mining Activities (Harare: Centre for Natural Resource Governance, 2017). It covers the Hwange Power Station (to which units 7 and 8 are currently being added) as well as the wider coal-related mining and industrial activities in the Hwange area. The report details significant air pollution from the power station, including sulphur dioxide, methane, carbon dioxide and ground-level ozone (which causes smog). The emissions also contain particulate matter (especially ash) from the plant’s outlet towers.21Moyo, Environmental Impact Assessment Report In 2021 it was reported that 400 households in a nearby village would have to move as a result of the new units’ air pollution.22“Over 880 Households [sic: the body of the article states 480 households] in Hwange Ingagula Face Relocation to Pave Way for ZPC Expansion Project”, ZWNews, May 21, 2021. The report makes it clear that while the relocation is a response to the increase in emissions that will be caused by units 7 and 8, communities in the area have suffered both air and ground pollution from the plant’s emissions for decades.

These direct impacts of the power plant are exacerbated by the project’s wider coal economy. Notable here is the open-cast Hwange coal mine. According to the CNRG, local communities (some of which are located within 100m of the plant) complain of pervasive dust pollution kicked up by mining activities such as drilling, blasting and transporting, and storing the coal at the various facilities in the area, including the thermal power plant. It notes that 250 000 tonnes of raw coal is stored on site at the power plant, leading to massive pollution from coal dust (a 50 000-tonne stockpile is estimated to release 250 tonnes of fugitive dust).

The open-cast mine and the stockpiles increase water pollution significantly, as rainwater and groundwater is acidified when passing over the exposed coal. The CNRG notes that the health of communities and animals has been affected, and that local wetlands have been damaged not only by runoff but also by airborne ash. This is also true of soil in the area, which shows high levels of pollution.

Even more alarmingly, the report notes that some underground coal seams are on fire. These long-smouldering fires endanger workers at the mines, and villagers reported an incident in which a boy was badly burned when he fell into one of these burning seams. Reportedly, the companies involved did not respond to requests for medical or other assistance in this case.23Moyo, Environmental Impact Assessment Report, 16.

Socio-economic

In May 2021 the Zimbabwean press reported that 480 households in the village of Ingagula, 100m away from the plant, would be displaced to make space for a 310km transmission line that forms part of the project. Project spokespeople insisted that these households would be compensated for the relocation, and that the entities involved were negotiating with local authorities to acquire land and construct new dwellings for the displaced villagers.24“Over 880 Households”.

However, the project manager of the Unit 7 and 8 expansion reportedly admitted that the estimated $60 million it would cost to move the 480 households had not been budgeted for in the original project planning, and that ZPC would have to raise it separately.25Leonard Ncube, “US$60m to Relocate 400+ Families from Hwange’s Ingagula Suburb”, The Chronicle, May 20, 2021. It was further revealed that three other communities between Hwange and the city of Bulawayo would also be affected by the construction of transmission lines.26Ncube, “US$60m to Relocate”.

In addition, local communities complain that these projects have not significantly increased employment in the area. This has been exacerbated by the enmeshing of the Hwange plant in the area’s wider coal economy. For example, there are allegations that workers at the Hwange Colliery Company have not been paid, and that the company is trying to evict them.27Simiso Mlevu, “Coal Investments in Zimbabwe: A Misplaced Priority”, CNRG, August 15, 2020. In July 2020 some of these workers sued the company. The lawsuit was reportedly focused on forcing the company to pay agreed-upon severance packages and to stop the workers from being evicted from company-owned housing, where some of them had lived for a decade.28“Hwange Colliery Ex-Workers Sue Coal Miner Over Evictions”, New Zimbabwe, July 17, 2020. The company has been involved in ongoing salary disputes for years, with claims of unpaid wages going back to 2013.29Ray Mwareya, “Miners’ Wives Take on a Zimbabwe Coal Giant to Pay Up Forgotten Wages”, Women’s Media Center, September 1, 2020. It was also reported that the company was planning on selling all the company housing in a bid to cover outstanding debts. This was despite the fact that many workers still occupied those dwellings and were still working at the company, despite complaints of unpaid wages.30“Struggling Coal Miner Wants to Sell Hwange Town Over $300m Debt”, New Zimbabwe, May 10, 2018.

Governance

The governance impact of the Hwange project is similarly problematic. As noted, there seems to be little enforcement of transparency from the authorities. Neither regular corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports from the company nor comprehensive environmental impact reports are publicly available.

There also does not seem to be any conflict resolution mechanisms in place between local residents and the plant, leaving communities dependent on NGOs, the media, protest action and lawsuits to raise their concerns.

This lack of transparency tends to fuel speculation of complicity between government officials and outside interests. For example, in 2018 a forensic audit at Hwange Colliery Company accused its then-head Winston Chitando of presiding over the misuse of a $115.5 million31US$. loan. He was also accused of colluding with the company’s board to divert profits, improperly trying to dismiss board members, and attempting to intimidate critics.32Andrew Kunabura, “Hwange Rotten To The Core – Audit”, Zimbabwe Situation, April 5, 2019; Veneranda Langa, “Minister Implicated in Hwange Looting”, NewsDay, November 14, 2018. Chitando was subsequently appointed as Zimbabwe’s minister of mines and mining development.

Comparison

Environmental

One of the most striking contrasts between the Indonesian and Zimbabwean case studies is how much more advanced both the technology and the mitigation measures were on the Indonesian side. Whereas the Jawa-7 project uses ultra-supercritical boilers, which boast lower emission rates than those stipulated by national coal-power plant regulations, the Hwange expansion uses sub-critical technology, with a demonstrably worse impact on the environment. This contrast is also true as regards water use. While Jawa-7 uses desalinated seawater, Hwange is dependent on piped-in river water. This means that, unlike Jawa-7, the Hwange expansion project is in direct competition with local communities for water, even as Zimbabwe is becoming more vulnerable to drought because of climate change.

Their different impacts on air quality do not stop at emissions. In the case of Zimbabwe, this is exacerbated by the emissions and dust caused by the nearby colliery, which supplies coal to the plant. As pointed out earlier, the emissions of the Hwange Expansion Project cannot easily be separated from those caused by adjacent mining, coking and other activities that feed into its operations. This is also true for the Jawa 7 project, despite its superior mitigation measures, pointing to the limits of environmental mitigation of coal power.

Socio-economic

The socio-economic dimensions of these projects reveal similar contrasts at the community level. On the one hand, both projects report measures to improve local infrastructure. However, in the case of Hwange, these measures are complicated by simultaneous efforts by authorities to resettle communities to make way for the transmission line and to mitigate ongoing pollution. The revelation that the original project budget did not contain allocations for either this resettlement or wider socio-economic mitigation confirms that, in the Zimbabwean case, socio-economic mitigation does not seem to have been high on the agenda.

These lapses continue in the case of employment. Jawa-7 claims to have created 7 000 jobs and to have invested in training. Yet communities say that jobs are going to Chinese workers. In comparison, local communities in Hwange complain that workers from elsewhere in Zimbabwe are favoured. In addition, ongoing labour and wage disputes at Hwange Colliery – which provides coal to the Hwange thermal plant – are evidence of a wider lack of socio-economic mitigation in the coal economy that undergirds the expansion project.

Governance

One of the most striking differences between the projects is how they slot into wider governance agendas. On the Indonesian side, the project followed the basic ESG mitigation and transparency parameters set by the Indonesian state, such as releasing public CSR reports. However, it has also received criticism for a lack of transparency from the tender stage onwards. It is particularly difficult to access the terms of the loan agreement and other financial details of the project. In this sense, it is an instance of the lack of transparency highlighted around Chinese BRI lending.

These factors are also at play in Zimbabwe, but they are exacerbated by the fact that Zimbabwe’s ESG standard-setting is a lot less robust than that of Indonesia. There are few publicly available CSR reports from the companies involved, and government environmental and other impact reports are largely lacking. Rather, the most comprehensive impact reports available come from civil society organisations and from Zimbabwe’s embattled, but vibrant, press. This strengthens the perception that there is little public accountability on either the corporate or the government side.

It is interesting that both projects have come in for criticism regarding their impact on their respective national emissions targets. However, within this impact, the Indonesian government seems at pains to provide concrete mitigation targets and implementation, and the corporate project partners seem to have responded to this standard-setting. In contrast, the Chinese firms in the Zimbabwean case seem to be responding to low levels of government standard-setting and implementation. Instead, their interaction with the community seems led by the high levels of secrecy and scant public trust that characterise Zimbabwean life more broadly.

That said, the choice by the Zimbabwean and Indonesian governments to pursue coalfired power seems driven by similar factors: local political will to exploit domestic coal reserves overriding longer-term worries about the environmental impact and the danger of stranded assets. The well-documented financial involvement of policymakers in the local coal sector in both countries arguably adds to this political will. This raises questions about how China’s recently announced ban on building foreign coal capacity will impact future relations.

Acknowledgement

This series of policy briefs was funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) as part of SAIIA’s Future-Proofing Africa’s Development series. SAIIA gratefully acknowledges FCDO’s support.