Executive summary

Much of the research into this field has focused on geopolitical and cybersecurity aspects. However, few studies have taken into account the environmental, socioeconomic and governance (ESG) aspects of these developments. This policy brief aims to address this gap by analysing the ESG impacts of two large Chinese ICT provision projects in Tanzania and Cambodia. It shows that, compared to other infrastructure developments, these projects had relatively limited ESG outcomes. While there were minimal environmental impacts, the success of socioeconomic mitigation was mixed and projects lacked transparency.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, China has been leading the world in infrastructure investment. The ICT sector has seen particularly fast growth: from 2000 to 2020, China’s internet users increased from 22.5 million to 989 million, including more than 160 million 5G network users.1China Internet Network Information Center, The 47th Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development, (Feb. 2021), https://www.cnnic.com.cn/IDR/ReportDownloads/202104/P020210420557302172744.pdf.

By the end of 2020, China had built the world’s largest optical fibre network and constructed 916 000 5G base stations, making up 70% of the global total.2‘China’s 5G network users exceed 160 mln: report,’ China Global Television Network, July 15, 2021, https://news.cgtn.com/news/2021-07-15/China-s-5G-network-users-exceed-160-mln-report-11UqIjq4BmU/index.html. China has committed to constructing a total of five million 5G base stations by the end of 2025 – a 25-fold increase in fewer than five years. The rollout of 5G networks, data centres and other high-tech infrastructure will result in an investment between RMB 10 trillion ($ 1.43 trillion) and at RMB 17 trillion ($2.51 trillion) by 2025.3Coco Liu, Lauly Li, Chen Ting-Fang and Kenji Awase, ‘China bets on $2tn high-tech infrastructure plan to spark economy,’ Nikkei Asia, June 1, 2020, https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/China-tech/China-bets-on-2tn-high-tech-infrastructure-plan-to-spark-economy

China’s strategy of economic transformation is focused not only on investing in ICT infrastructure, but on a much broader digital economy, which has increased its share in China’s GDP from 14.2% in 2005 to 38.6% in 2020, and is expected to grow to 70% by 2025.4China Academy of Information and Communications Technology, White Paper on China’s Digital Economy Development 2021, 2020, http://www.caict.ac.cn/english/research/whitepapers/202104/P020210429540525737660.pdf.

The Digital Silk Road

China has placed ICT development at the forefront of its global strategies. The Digital Silk Road (DSR) serves as a key pillar under China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) strategy by promoting the construction and interconnection of ICT globally. This strategy calls for the construction of cross-border optical cables and expansion of communications networks to facilitate digital connectivity among BRI countries.5As of March 2021, 139 countries have joined the BRI. David Sachs, ‘Countries in China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Who’s in and who’s out,’ Council on Foreign Relations, blog, March 24, 2021, https://www.cfr.org/blog/countries-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-whosand-whos-out. It prioritises an increase in cross-border trade using e-commerce business models and raising trade through investment. By 2019, China had signed DSR MOUs with 16 countries and e-commerce MOUs with 19 countries.6Gu Yang, ‘Digital Silk Road will become the new engine of global development’, Economic Daily, September 9, 2019, http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-09/09/content_5428411.htm..

Multiple major policy initiatives support these goals: the National Informatization Strategy (2016 – 2020) calls upon China’s internet companies to “go out” into the world and support the creation of the DSR. The “Made in China 2025” and “Internet Plus” policy initiatives were launched in 2015 to drive domestic industrial and digital innovation.7Kristin Shi-Kupfer and Mareike Ohlberg, China’s Digital Rise: Challenges for Europe, Mercator Institute for China Studies, no. 7, (April 8, 2019), https://merics.org/en/report/chinas-digital-rise The New Infrastructure Initiative, launched in 2020, is a comprehensive plan that aims to integrate and facilitate China’s efforts to build ICT infrastructure as “next-generation technology”. The DSR combines a domestic push to export Chinese technologies with a broader agenda to augment compatibility between Chinese and overseas networks.

The key areas of investment in the DSR span hard infrastructure (including telecom networks and satellite tracking stations), digital economic platforms, financial technology and security-related services and platforms. China aims to establish four large international information passages to link countries in the BRI to higher internet speed by 2025.8State Council General Office, ‘Outline of the National Informatization Development Policy,’ China Copyright and Media, July 27, 2016, https://chinacopyrightandmedia.wordpress.com/2016/07/27/outline-of-the-national-informatization-development-strategy/.

China’s ICT infrastructure regulation

The regulatory structure governing China’s ICT sector has experienced significant transformation since the late 1990s. In 1998, the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications and the Ministry of the Electronic Industry were merged into the Ministry of Information Industry (MII), the main regulator of telecommunications. In 2008, the Chinese government created the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) after consolidating bureaucratic and industrial interests between the MII and other industryspecific departments. While its most important task was the modernisation of China’s ICT infrastructure, the MIIT has changed from an ICT-specific Ministry to a super-ministry responsible for all types of industries.

Alongside MIIT, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) takes charge of plans and public investment while the Ministry of Science and Technology (MST) supports research and development (R&D). There is also a newly appointed Central Cybersecurity and Informatization Commission, composed of 21 ministers, focused on long-term cybersecurity and informatisation strategy and planning, as well as inter-agency coordination.

The NDRC is the lead agency and driver for the BRI and plays a key role in approving overseas investment related to connectivity, advanced manufacturing and R&D. The Cyberspace Administration of China oversees China’s cybersecurity and digital economy initiatives. It is also a key player in Beijing’s efforts to build a data governance system, which will grow in importance for companies’ development of DSR-related platforms and services. The MST and the MIIT plan to cooperate with counterpart ministries across BRI countries on science, technology and ICT issues, laying the groundwork for Chinese companies to enter and expand their access to these markets.

Major ICT players

China’s digital platform drive combines corporate initiatives from domestic telecom giants with the state-led push to integrate traditional industries using advanced ICT. Three major Chinese telecom operators (China Mobile, China Unicom and China Telecom) play a significant role building infrastructure to accelerate 5G coverage across major cities. Following the government’s pledge to accelerate infrastructure construction to combat economic pressure, investment has increased significantly. By highlighting the success of these domestic initiatives in their marketing campaigns, vendors and carrier services could encourage support for 5G across BRI countries, as part of the DSR initiative.

Unlike the state-owned conglomerates leading BRI infrastructure projects, DSR participants tend to be newer, private Chinese tech firms that are leading in strategic digital industries locally and increasingly globally.Huawei, Alibaba, Tencent, JD.com and Didi have made substantial investments overseas. Huawei and ZTE are the two leading Chinese providers of ICT infrastructure globally; more than half of their total revenue is generated from overseas businesses. For example, by 2021, Huawei had built over half of the 140 commercial 5G networks deployed in 59 countries. Despite US trade restrictions, Huawei and ZTE increased their respective shares of the global telecom infrastructure market, driven in part by China’s accelerated 5G deployment. Huawei’s share rose from 28% in 2019 to 31% in 2020, ZTE’s from 9% to 10%.9Stefan Pongratz, ‘Key Takeaways: Total Telecom Equipment Market 2020,’ Dell’Oro Group, March 8, 2021, https://www.delloro.com/key-takeaways-total-telecom-equipment-market-2020/.

Alibaba and Tencent are deploying internet data centres globally at an accelerating pace. Alibaba has built data centres in 24 regions and 74 availability zones and Tencent is available in 27 regions and 66 availability zones.10He Wei, ‘Data centers tap growing market,’ China Daily, June 5, 2021, http://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202106/05/WS60bac608a31024ad0bac3c96.html. Alibaba prioritises its payment system AliPay via Ant Financial, which has led major investments in payments companies in East Asia, Southeast Asia and Europe.

The DSR is inextricably linked to China’s efforts to promote its preferred technical standards to the benefit of Chinese companies.11Elsa Kania, ‘China’s play for global 5G dominance – standards and the “Digital Silk Road,’ The Strategist, June 27, 2018, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/chinas-play-for-global-5g-dominance-standards-and-the-digital-silk-road. China has contributed to a large and growing number of projects, which reportedly amount to an estimated $79 billion worldwide. These projects include fibreoptic cables, telecommunications equipment and smart-city initiatives, among others.12Sheridan Prasso, ‘China’s Digital Silk Road Is Looking More Like an Iron Curtain,’ Bloomberg, January 10, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2019-01-10/china-s-digital-silk-road-is-looking-more-like-an-iron-curtain.

China’s role in Southeast Asia’s ICT infrastructure

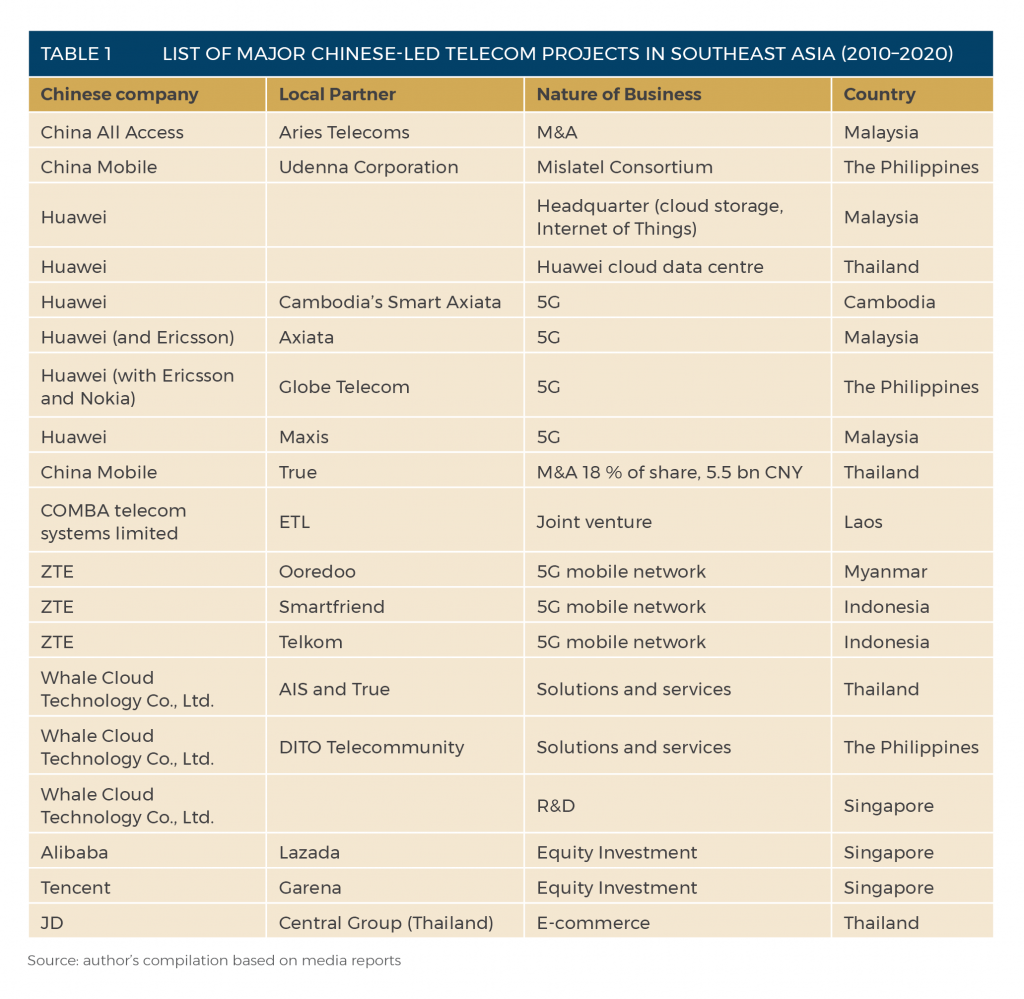

China has entered the Southeast Asian market largely through joint ventures with and investments in local telecom companies (see Table 1). Among all Chinese telecom companies, Huawei is the most active in building ecosystems for digital economy in the region, especially via smart city projects through the ASEAN Smart Cities Network. Other major players include China Mobile, ZTE, Alibaba and Tencent.

Multilaterally, China has set up mechanisms such as a standardisation cooperation agreement between China and ASEAN’s standards docking and China-ASEAN Information Center, which is aligned with ASEAN’s regional connectivity ambitions. Given the complementary role of Chinese telecom-related investments to ASEAN regional digital connectivity, this region is generally receptive to Chinese telecom investment. This is bolstered by its quality and affordability. For poorer countries in the region, such as Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar, the availability and cost of physical infrastructure represent barriers to digital connectivity, to the disadvantage of rural areas. As more developed countries, such as Thailand and Malaysia, explore the benefits of 5G broadband in building Smart City Networks and disaster management protocols, Chinese experiences in using telecom technology provide attractive options for the region.

While much public attention has fallen on Chinese companies’ involvement in developing 5G networks, China’s investments in fibreoptic networks, crucial for the connectivity of the DSR, has received less attention. In Southeast Asia, Chinese firms’ involvement in the construction of fibreoptic cables has risen from 6% of all projects between 2012 and 2015 to 20% between 2016 and 2019.13Thorsten Benner, et al., Authoritarian Advance: Responding to China’s Growing Political Influence in Europe, Global Public Policy Institute and Merics, February 2018, 18. https://merics.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/GPPi_MERICS_Authoritarian_Advance_2018_1.pdf. Chinese companies have completed more than a dozen undersea fibreoptic cable projects and nearly 20 more are under construction.14Brian Harding, ‘China’s Digital Silk Road and Southeast Asia,’ Center for Strategic & International Studies, February 15, 2019, https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-digital-silk-road-and-southeast-asia.

Southeast Asia case study: Submarine fibreoptic cable in Cambodia

HyalRoute is a leading Chinese provider of telecom infrastructure services in Southeast Asia.15HyalRoute, ‘Company Profile,’ http://www.hyalroute.com/aboutus/company-profile/. In 2016, the Fiber Optic Communication Network (CFOCN), a branch of HyalRoute Group, signed an agreement with the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications for a 380 km submarine fibre optic cable network. This project formed part of the Asia-AfricaEurope-1 (AAE-1) submarine network via the Gulf of Thailand off the coast of Sihanoukville. The total investment was $69.7 million for a period of 25 years.

The AAE-1 project was considered a milestone as it connected cable networks from Asia to Europe and Africa, as well as the majority of Southeast Asian countries. The project also aimed to supply telecom infrastructure services and equipment from China to Cambodia, to help Cambodia improve its telecom services with cost-efficient high-speed internet service for both industrial and individual users. Relieving Cambodia’s heavy dependence on Vietnam for network sustainability was an additional aim.

HyalRoute has made great efforts to localise itself in Cambodia by relying heavily on local labour, local elites and adhering to local legal frameworks. It adopted the common practice of assessing environmental and social impacts of infrastructure projects.16HyalRoute, ‘Cambodia: Our Operation and Networks,’n/d http://www.hyalroute.com/cambodia/. The survey report of the AAE-I project indicates that CFOCN works closely with relevant Cambodian government ministries and agencies. Overall, the report emphasises the project’s observation of local regulations.

The submarine cable’s environmental impact on residents’ health, marine life and ecological biodiversity is limited. To compensate for any impact on local employees, the company provided public health measures such as clean water and vaccinations.

Transparency remains a major issue in the project. Basic information, such as financing, procurement and employment, is missing from the Environmental Socioeconomic Impact Assessment (ESIA) report. However, the company has made more information available in its AIIB-sponsored projects, indicating that it can adapt to more rigorous standards.

China’s role in Africa’s ICT infrastructure

China’s involvement in Africa’s ICT infrastructure coincided with Africa’s telecom revolution in the 1990’s, when many African countries liberalised these sectors and upgraded their infrastructure. The telecom sector has grown considerably in the past few decades, with most growth driven by the widespread use of mobile phones and broadband (fixed and mobile) for internet access. Africa has outpaced much of the world in this sector.

While African countries have benefited greatly from infrastructure development aided by China, Chinese companies have also gained access to the continent’s infrastructure and consumer markets. This is further supported by the government’s role in promoting Chinese companies in overseas markets.

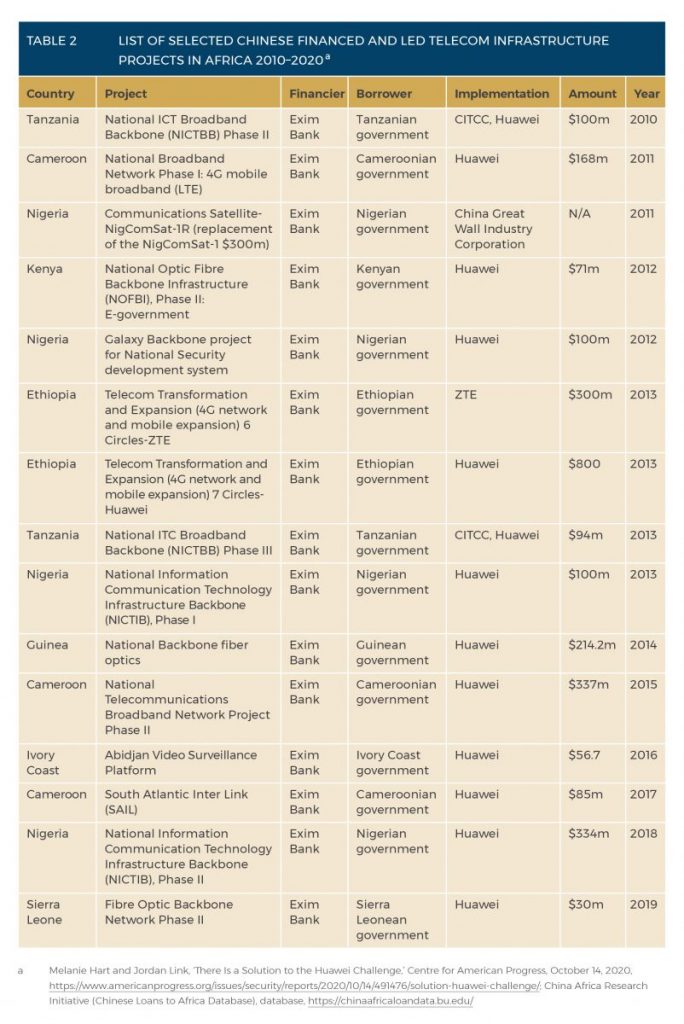

Bolstered by loans from state-backed policy banks such as the Export-Import Bank of China (China Exim) and China Development Bank, along with support from the ChinaAfrica Development Fund, China’s major ICT companies have enabled the full development of telecom infrastructure in Africa. The Chexim model of financing that mandates the use of Chinese suppliers and equipment further cements Chinese tech firms’ dominance in African countries. This dominance in turn could set the standards and norms in the sector.

Africa case study: National ICT broadband backbone – Tanzania

The Tanzanian National ICT broadband fibreoptic backbone (NICTBB), launched in February 2009, was a flagship project aimed to provide higher capacity ICT services at affordable costs and transform Tanzania into East Africa’s digital hub. The project was financed primarily by loans from China Exim Bank of about $264 million and implemented by Chinese International Telecommunications Construction Corporation (CITCC), a subsidiary of the state-owned China Telecom, in collaboration with Huawei.17AidData Loans Database, https://china.aiddata.org/projects/23142.

The NICTBB project was a much-needed infrastructural intervention in Tanzania’s telecom sector. It has proven beneficial for the larger ecosystem of industries, businesses and individuals as well as for the East African telecoms landscape. The NICTBB has also brought Tanzania better connectivity and increased adoption of ICT and e-services. The deployment of the NICTBB was lauded for significantly increasing broadband connectivity in Tanzania.18Steve Esselaar and Lishan Adam, ‘Understanding what is happening in ICT in Tanzania,’ Africa Portal, November 29, 2013, https://www.africaportal.org/publications/understanding-what-happening-ict-tanzania-supply-and-demand-side-analysis-ict-sector/ It has fostered e-education, connecting 28 higher learning and research institutions with last mile connectivity.19The United Republic of Tanzania National Audit Office, Report of the controller and auditor general on the audit of Financial statements of the Regional Communications Infrastructure project (RCIP) C.4614-TA for the Financial year ended 30th June, 2017, (January 2018), https://rise.esmap.org/data/files/library/tanzania/TANZANIA%20Supporting%20Documents/CC/CC%2015%20Tanzania%20TANESCO%20Report%20of%20the%20Controller%20and%20Auditor%20General%20on%20the%20Consolidated%20Financial%20Statements%202017.pdf. This has enabled the adoption of online application and admissions processes and facilitated the wider adoption of e-government in Tanzania.20S Pazi. and C Chatwin, ‘The Impact of NICTBB in facilitating the E-services and M-services in Tanzania,’ International Journal of Economic and Management Engineering 8, vol. 3 (2014): 823-829, https://publications.waset.org/9997991/the-impact-of-nictbb-infacilitating-the-e-services-and-m-services-in-tanzania.

In terms of job creation and technology transfer, the NICTBB project is a mixed story. The CITCC has created over 9 000 local jobs, accounting for 60% of the company’s workforce.21Hezron Makundi, Huib Huyse and Patrick Develtere, ‘Cooperation between China and Tanzania on ICT: fish, fishing tackle or fishing skills?’ Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies, 14 vol. 2 (2016): 129-149. While this has paved the way for skills and knowledge transfer, participation of local firms was restricted to the lower end of the technology value chain.22Veda Vaidyanathan and Jumanne Gomera, “Power and communications infrastructure,” chap 5 in China’s Infrastructure Development in Africa, no 5 (Institute of Chinese Studies, November 2019). https://www.icsin.org/uploads/2019/12/11/c924317a941e3d430099f6f7d652abf2.pdf. Acquisition of goods and services for the construction of the NICTBB was restricted to the procurement regulations of the Chinese government.

Limited focus on capacity building by the Chinese contractor has resulted in inadequate local operation and management of the infrastructure.

Although debt sustainability hasn’t been a concern of the project, the underutilisation of the infrastructure has limited the Tanzanian government’s ability to generate substantial revenues and recoup its costs.23August B Kowero, Exploiting the potentials of the National Information and Communication Technology Broadband Backbone (NICTBB) in Tanzania, Tanzania Country Level Knowledge Network, a study report, (July 2012), https://www.tanzania.go.tz/egov_uploads/documents/pj_en.pdf. High tariff rates, connectivity prices, lack of local content, unfavourable government policies, poor after-sales support and management and lack of public awareness of the NICTBB were also identified as reasons for its poor uptake.24Kowero, Exploiting the potentials. To accelerate broadband adoption, the Tanzanian government would need to recover the costs of the infrastructure while ensuring relatively low-cost wholesale access.

Comparison and conclusion

The Digital Silk Road serves as a key pillar for China’s involvement in ICT infrastructure and connectivity in Africa and Southeast Asia, as a financier, builder, owner and operator. It is of strategic importance as China enhances its digital connectivity abroad and sets technical standards and norms in the ICT sector.

China’s engagement in ICT abroad has been marked by certain patterns. First, China’s involvement in Africa’s ICT infrastructure construction began in the 1990s; investment in Southeast Asia is a recent phenomenon driven by a mix of private and state-linked companies. Second, ICT projects in Africa are largely driven by government-to-government initiatives and backed by concessional lending agreements; in Southeast Asia, Chinese companies undertake the construction of ICT service, equipment, manufacturing and communications operators through market bidding and non-concessional loans. Third, while Chinese projects contribute significantly to local job creation, Chinese companies have made greater efforts in Southeast Asia than in Africa to use local labour, engage with local elites and observe local legal frameworks.

Chinese-financed infrastructure initiatives in Africa and Southeast Asia have been subject to scrutiny and broader debates about their motivations, financial modalities and environmental, social and governance impacts. While these issues are relevant in the analysis of Chinese telecoms infrastructure provision, the more prominent concerns are social exposures stemming from data security, social cohesion and safety management risks. In both African and Southeast Asian cases, claims of opaque contracting practices and lack of transparency in financing agreements are commonly levelled against Chinese projects.

Acknowledgement

This series of policy briefs was funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office as part of SAIIA’s Future-Proofing Africa’s Development series. SAIIA gratefully acknowledges FCDO’s support.