Recommendations

- Special economic zones (SEZs) have proven to be an effective strategy to attract foreign investment. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) will make these zones even more inviting, given the market potential. African countries should continue to leverage SEZs.

- African countries need to prioritise institutional capacity building to strengthen their engagement with foreign infrastructure financiers.

- African countries should leverage the AfCFTA to reach regulatory harmonisation for Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) technologies, which will offer foreign businesses an inviting market while attracting investment to the continent.

Executive summary

Africa’s engagement with China has grown considerably over the past two decades, and this growth trajectory is bound to continue. For African countries and China, it is important to take stock of the gains made. This policy briefing assesses the economic dimensions of China–Africa relations by examining trade, infrastructure financing and development, as well as digital engagements between these partners. It also looks at how sustainable development can be increased within the different facets of this ongoing relationship, to enhance inclusive benefits for all. The policy briefing draws on a series of dialogues hosted by SAIIA and the Chinese Embassy in South Africa, under the China–Africa Joint Research and Exchange Programme, on 13 and 15 October 2020. It captures key elements of the discussions and recommendations drawn from academics and experts throughout the deliberations.

Introduction

Africa’s engagement with China has grown exponentially over the past two decades, and is set to continue this growth trajectory. It is important that both African countries and China take stock of the gains made. As the scale and complexity of the relationship increases, it becomes necessary to unpack its emerging challenges and new dimensions. With a view to this, SAIIA and the Chinese Embassy in South Africa, under the China–Africa Joint Research and Exchange Programme, hosted policy dialogues on 13 and 15 October 2020. These were aimed at unpacking the pertinent economic and development dimensions of this ongoing relationship.

The key objective of the dialogue series was to explore sustainable development, which is at the forefront of African policymakers and researchers’ agendas. It is also a critical dynamic within Africa–China relations. In the African context, the AfCFTA offers enormous opportunities to promote intra-continental trade, while partners such as China can provide critical intermediate inputs into African value chains. To achieve these benefits, governments will need to look beyond traditional infrastructure financing models to enable the free flow of goods, services, capital and people across the continent. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is thus an essential part of this equation. At the same time, these new opportunities and modalities need to be explored within the context of climate change and the 4IR. It is also necessary to consider the coronavirus pandemic, which has had a myriad economic impacts.

This policy briefing captures key elements of the discussion over the course of the dialogue series, as well as recommendations drawn from participating academics and experts.

Enhancing economic development and cooperation

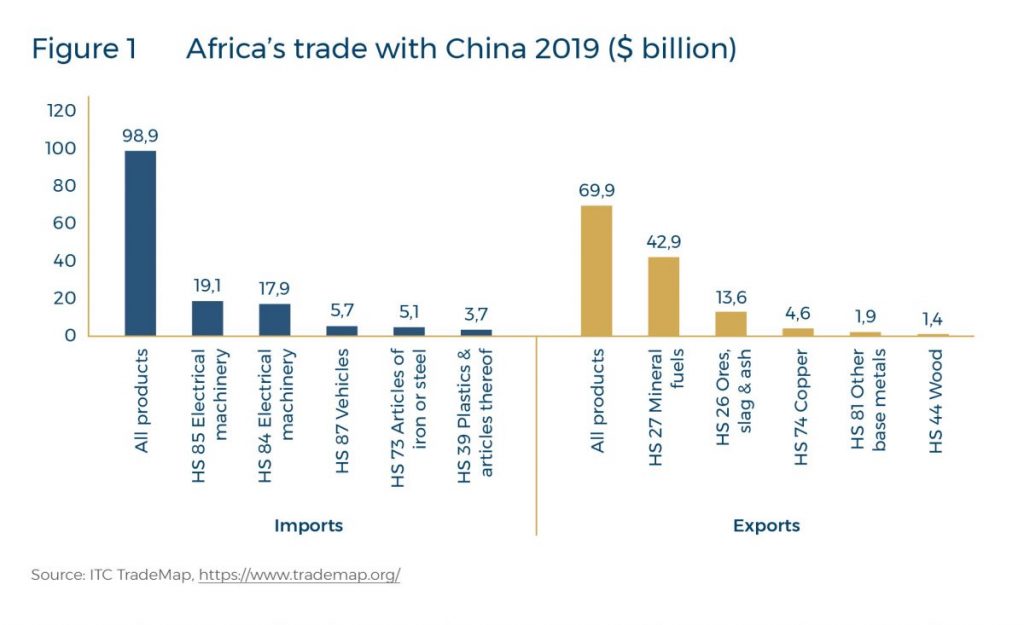

Total trade between Africa and China reached almost $170 billion in 2019 (Figure 1), up from roughly $110 billion a decade earlier. Taking total trade and this upward trajectory as a proxy for the economic relationship between these partners, Africa and China will continue to enjoy growing economic relations.

For many African countries, industrialisation and the associated benefits – increased employment, higher value exports and greater revenues, for example – are key development priorities

Yet a key dynamic of this trade relationship – and one that African countries are very conscious of – is its inequable nature. Africa continues to export primary commodities to China (eg, oil, ore, copper, metal and wood) and import manufactured goods (eg, machinery and vehicles) or processed items (eg, iron and plastic) from it (Figure 1). For many African countries, industrialisation and the associated benefits – increased employment, higher value exports and greater revenues, for example – are key development priorities. This has been an ongoing area of dialogue and cooperation with Chinese counterparts.

One of the main ways in which this inequable trade relationship can be addressed is increasing direct investment. Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Africa has increased rapidly over the past few years, with FDI flows to Africa reaching $4.11 billion in 2017, up 70.8% from the preceding year.1Weiwei Chen, “China’s Manufacturing and Africa’s Industrialisation: A Case Study of Chinese Manufacturing Investment in Ethiopia”, South African Institute for International Affairs, Presentation, October 2020, https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/3-Weiwei-Chen.pdf.During the 2018 Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) Summit, President Xi Jinping set a target of $10 billion in FDI in Africa between 2018 and 2021.2Chen, “China’s Manufacturing and Africa’s”.

Some countries in Africa have managed to successfully tap into FDI flows from Chinese firms in the manufacturing sector. The experience of Ethiopia and China shows the importance of SEZs, which offer investors favourable incentives, to facilitate inward FDI flows. Under its FDI strategy Ethiopia also actively sought out technologically advanced firms and leaders in their respective industries, which led crowding in other smaller investors. By branding its investment opportunities under China’s BRI, Ethiopia attracted even more FDI. Ultimately, there was an alignment of interests between Addis Ababa and Beijing, with Ethiopia attracting investment and enhancing manufacturing capacity and China exporting surplus capacity in labour-intensive industries.3Chen, “China’s Manufacturing and Africa’s”.Other African countries would do well to learn lessons from how Ethiopia and China achieved this mutually beneficial cooperation.

Beyond bilateral relations, the impending launch of the AfCFTA is a unique opportunity for African countries to crowd in Chinese FDI

Beyond bilateral relations, the impending launch of the AfCFTA is a unique opportunity for African countries to crowd in Chinese FDI. About 97% of tariffs on trade between African countries will be zero-rated. Given the potential market size of more than 1 billion people, this will be an attractive offering for foreign firms. However, given the strict rules of origin required for goods to qualify for duty-free trade under the AfCFTA, the need for local value addition will be high. Foreign firms will have to invest and manufacture in African countries if they want to take advantage of duty-free trade under the AfCFTA. SEZs – with attractive tax, tariffs and other benefits for foreign firms – will be particularly alluring in this regard.4Cyril Prinsloo, Understanding the African Continental Free Trade Agreement, Special Report (Johannesburg: SAIIA, February 26, 2020), https://saiia.org.za/research/understanding-the-african-continental-free-trade-agreement/.Ultimately, not only will increased Chinese FDI benefit African countries and their ambitions to increase domestic manufacturing but it will also provide a source of intermediate goods and strengthen value chains between the continent and China.

For their part, African countries must actively work to reduce the inequable nature of trade by being proactive about engaging the Chinese market. An analysis of exports from Asia, Latin America and Africa to China during the US–China trade war (which created significant external demand for agricultural goods in China as related trade from the US plummeted) showed that other regions are more proactive in engaging the Chinese market and taking advantage of market opportunities.5Bhaso Ndzendze, “Turning Crises into Opportunity: Agricultural Exports to China During the Trade War” (Occasional Paper 309, SAIIA, Johannesburg, July 2020), https://saiia.org.za/research/turning-crisis-into-opportunity-agricultural-exports-to-china-duringthe-trade-war/.There is an opportunity for African countries and China to discuss particular frameworks of agricultural cooperation under FOCAC, such as trade facilitation and purchase commitments, or explore joint agricultural ventures. Joint agricultural ventures between African and Chinese businesses will also give African countries greater knowledge of, and access to, Chinese markets.6Ndzendze, “Turning Crises into Opportunity”.

Increasingly, Africa–China economic cooperation will be defined by the need to not merely grow but grow sustainably. This is pertinent in the post-COVID-19 era, where for many countries the emphasis will be not merely on economic recovery and mitigating the shortterm economic impact of the pandemic but also on using this as an inflection point to rebuild economies more inclusively. Africa and China can explore this by ensuring greater uptake of green bonds to finance sustainable business and infrastructure, or promoting dialogue between policymakers and businesses on improved policy and regulatory measures that promote inclusive economic activities. One such measure could be putting in place de-risking mechanisms for green investment or credit enhancement, which will attract green private capital.7Palesa Shipalana, “Green Financing Mechanisms for Developing Countries – Emerging Practice”, SAIIA, Presentation, October 2020, https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/1-Palesa-Shipalana-1.pdf.

Infrastructure investment and development

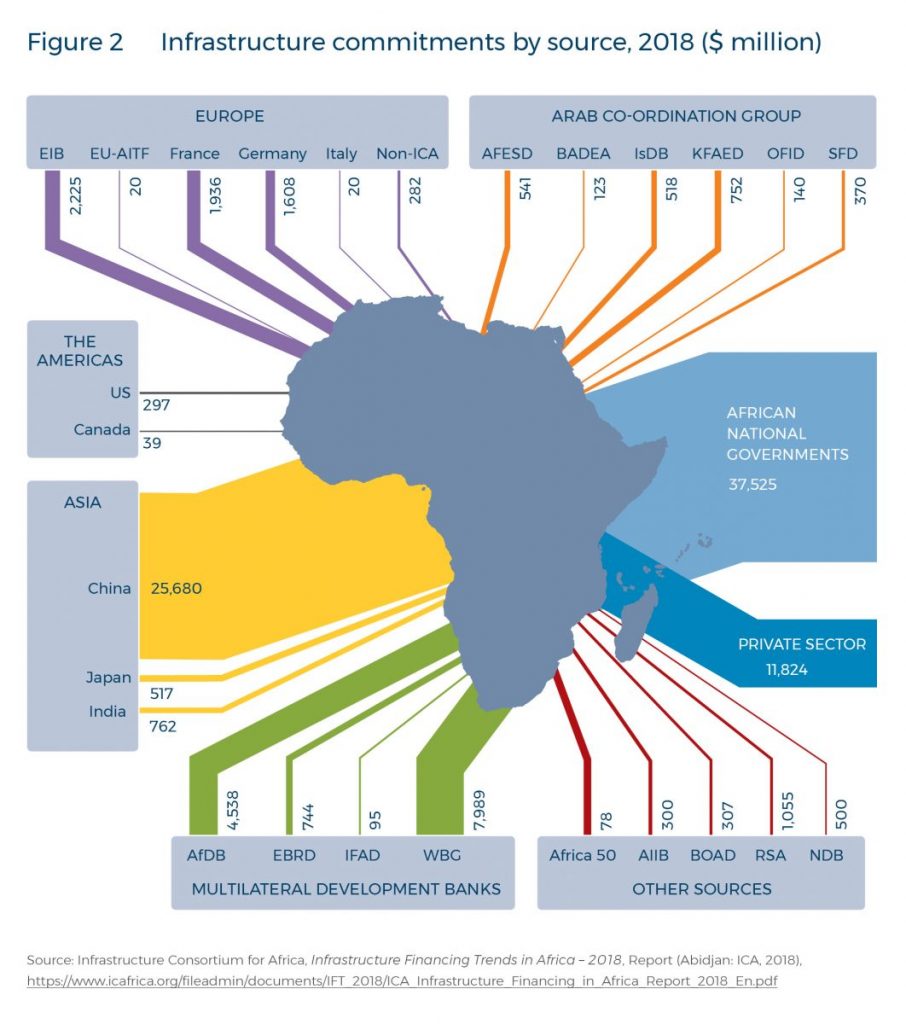

Beyond economic cooperation, infrastructure financing and development remain key tenets of Africa–China relations. In 2018 Chinese infrastructure commitments in Africa exceeded $25.6 billion, making it by far the largest single source of financing after African governments themselves (Figure 2). As the continent continues to face a significant infrastructure financing deficit (currently estimated at $108 billion annually),8AU Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa, “Africa’s Infrastructure Deficit and Risk Mitigation”, June 27, 2018, https://www.au-pida.org/news/africas-infrastructure-deficit-and-risk-mitigation/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20AfDB’s%20 African,currently%20estimated%20at%20%24108%20billion.with growing debt stocks and servicing costs, these are pertinent dimensions of Africa–China infrastructure relations. On the one hand, infrastructure is a major enabler of economic growth and development and China’s efforts under the BRI can help address this challenge. On the other, many have become concerned about Africa’s growing debt stock and debt servicing costs, especially in the fiscally constrained post-COVID-19 environment, and China’s growing share of debt exposure on the continent.

China’s BRI, which lists 40 African partner countries, presents significant opportunities for these countries to reduce their infrastructure financing deficit, through key projects such as the Mombasa–Nairobi railway and the Addis Ababa light railway line. Chinese funding under the BRI fills a major financing gap for African countries, as many other financiers’ funding pools are geared towards social infrastructure, while private capital markets remains expensive.9Mma Amara Ekeruche, “Chinese Infrastructure Investment and the Belt and Road Initiative in Africa”, SAIIA, Presentation, October 2020, https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Chinese-Infrastructure-Investment_141020.pdf.

However, despite Africa’s infrastructure financing needs, governments (African and elsewhere) should be concerned about mounting debt stocks and debt servicing costs. Many African countries borrowed heavily to finance infrastructure on the back of expectations of higher revenues from commodities. A significant drop in commodity prices, combined with a global economic slowdown towards the end of 2019, limited fiscal space and mounting costs to counter the pandemic, placed governments and lenders on alert. It is expected that revenues for African countries in 2020 were slashed by $45 billion as a result of these factors. At the same time, debt service costs were expected to increase to $40 billion annually.10Peter Fabricius, “Indebted Africa: China’s Role in Getting Africa Into and Out of Debt”, SAIIA, Presentation, October 2020, https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/1-Peter-Fabricius-1.pdf.

China’s growing role as a financier of infrastructure in Africa, together with increasing geo-political competition with the West, has perhaps seen it unfairly critiqued. Chinese Ambassador to South Africa Chen Xiaodong has dismissed three core fallacies: the debt trap, strategic asset plundering and neo-colonialism.11The full speech can be accessed at SAIIA, “Focusing on New Dimensions of Growth and Ushering in a New Stage in for China–Africa Cooperation”, October 2020, https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Keynote-Speech-by-H.E.-Ambassador-designateChen-Xiaodong-of-China-to-South-Africa-1.pdf.Independent research supports the position that geopolitics have heavily tainted the narrative around Chinese infrastructure financing in African countries.12Deborah Brautigam, “China, the World Bank, and African Debt: A War of Words”, The Diplomat, August 17, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/08/china-the-world-bank-and-african-debt-a-war-of-words/.

China’s growing role as a financier of infrastructure in Africa, together with increasing geo-political competition with the West, has perhaps seen it unfairly critiqued

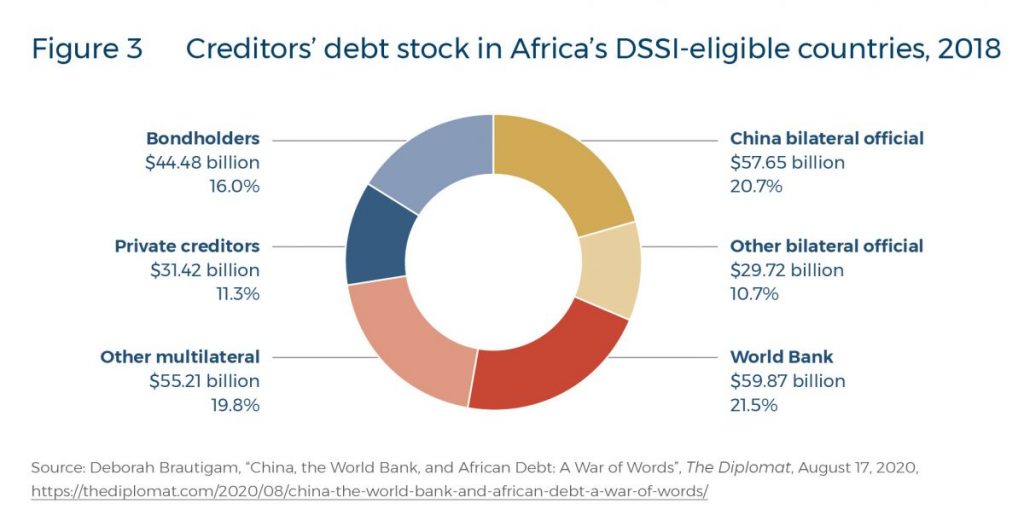

Instead, the major source of concern regarding debt sustainability is that neither private creditors nor multilateral lenders participate in the biggest global debt relief initiative, the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI). Together, private creditors and multilateral lenders account for $152.61 billion (68.6%) of the total debt of DSSI-eligible countries (see Figure 3).

Nevertheless, China’s share of outstanding African debt remains considerable, at $57.65 billion (20.7% of the total). It has already taken some encouraging actions in this regard: it has joined the DSSI, signed debt suspension agreements between the Exim Bank of China and African countries, and waived interest-free loans due to mature at the end of 2020 for 15 African countries.13SAIIA, “Focusing on New Dimensions”.Going forward, China should also consider extending local-currency loans, as this will assist countries in mitigating currency risks and ensure longer-term debt sustainability.

It should, however, be noted that external creditors alone cannot be held accountable for Africa’s debt crises. African countries should take more responsibility for macroeconomic and fiscal management. Research shows that institutional capacity to manage sizeable infrastructure finance is not a priority for African countries.14H Zhou, “Misplaced Anxieties? China, Traditional Donors, and Institution Building & Restructuring in Uganda’s Roads Sector”, unpublished presentation.In order to improve China–Africa cooperation on infrastructure, as well as with other financiers, African countries need to prioritise institutional capacity to manage fiscal matters.

Africa–China cooperation on the 4IR

For many African countries, the 4IR presents two serious challenges: it could pose a threat to employment opportunities, and increase the digital divide between Africa and the rest of the world. At the same time, the 4IR also presents the continent with massive opportunities.

The 4IR will bring about many as-yet-unknown social, economic and political disruptions. One of the key trends already being witnessed is the growing mechanisation of industries and manufacturing processes. If anything, the COVID-19 pandemic illustrated how quick the uptake of new technologies such as electronic payments and ecommerce can be

For many African countries, the 4IR presents two serious challenges: it could pose a threat to employment opportunities, and increase the digital divide between Africa and the rest of the world

in African countries.15Alastair Tempest and Michelle Chivunga, “Mapping Innovations for the African Free Trade Area in Post COVID Times”, SAIIA, Presentation, October 2020, https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/2-Alastair-Tempest-Michelle-Chivunga-1.pdf.For African countries that have earmarked manufacturing as a key driver of employment for a growing youthful population, this has become a serious concern. Policymakers can manage this trend in two ways: embrace automation or manage the automation process. Embracing automation entails leveraging this process to take advantage of efficiencies, value addition and ultimately increased revenue generation, while also future-proofing populations to deal with the impacts through education and social safety security nets. The latter approach – managing automation – involves maximising current opportunities where traditional manufacturing is still labour intensive, while safeguarding strategic sectors from large-scale automation. For most countries, a combination of these two strategic approaches, tailored to specific structural and socioeconomic needs, will likely be the best way forward.16Kartik Akileswaran, “Adapting Development Strategy in Africa to the 4IR”, SAIIA, Presentation, October 2020, https://saiia.org.za/wpcontent/uploads/2020/10/3-Kartik-Akileswaran-1.pdf.

Irrespective of the approach to the 4IR that African countries choose to take, they need to minimise the existing digital divide so widespread on the continent vis-à-vis other areas across the globe. Physical digital infrastructure will be the backbone of the 4IR. But it is also important that African countries create a regulatory and policy environment that allows innovation and technologies to flourish. This includes innovation-friendly regulations for issues such as intellectual property, and regulation that supports data protection but does not strangle the free flow of data across borders.

As African countries gear up for round two of the AfCFTA negotiations (on services), this should be at the forefront of their agendas. It is crucial to address issues such as free flow of data among African countries, consumer protection principles on the continent, and

It is crucial to address issues such as free flow of data among African countries, consumer protection principles on the continent, and the use of digital services within the AfCFTA to facilitate trade effectively and reduce non-tariff barriers

the use of digital services within the AfCFTA to facilitate trade effectively and reduce nontariff barriers.17Tempest and Chivunga, “Mapping Innovations”.Leveraging the AfCFTA is an important lesson African countries can learn from China: Beijing has managed to leverage its market size and potential to influence how foreign investors behave in China and how they enter the market.18L Johnston, comment contribution, “China-Africa Joint Research & Exchange Programme Webinar Series”, October 15, 2020.At the regulatory level African countries should collaborate and use their collective market potential to attract foreign businesses and investors.

Examples of positive uses for technology in African countries abound. Twiga (Kenya) facilitates trade between farmers and markets without intermediaries; BenBen (Ghana) uses distributed ledger technology to securely transfer land; and Acquahmeyer (Ghana) rents drones to farmers to monitor crop health. Africa should also reach out to China to learn from it. China is a leader in technological prowess and leveraging technology to achieve development gains. FOCAC is an ideal platform to facilitate such inter-stakeholder dialogue and lesson sharing.

Conclusion

Based on current Africa–China relations, this relationship will continue to expand in scope and depth. It is important that policymakers take stock of challenges and opportunities to enhance mutually beneficial relations. Exciting opportunities loom, including the AfCFTA and advancements in technology, which should be harnessed to promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth in African countries.

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful to all scholars and policymakers who participated in and contributed to the ‘New Dimensions of Growth and Development in Africa–China Cooperation’ dialogue series, hosted on 13 and 15 October 2020. I am also grateful to the China–Africa Joint Research and Exchange Programme for supporting this dialogue series and publication, as well as the Embassy of China in South Africa for its support.

SAIIA gratefully acknowledges the support of SIDA for this publication.