The pattern of interaction has oscillated from President Mandela’s principled stance against General Sani Abacha’s dictatorship in the late 1990s, to close and effective engagement between Presidents Thabo Mbeki and Olusegun Obasanjo during the last decade. Under Presidents Jacob Zuma and Goodluck Jonathan, relations reached a low-point with the two continental powers unable to reach agreement on the chairmanship of the African Union Commission in 2012.

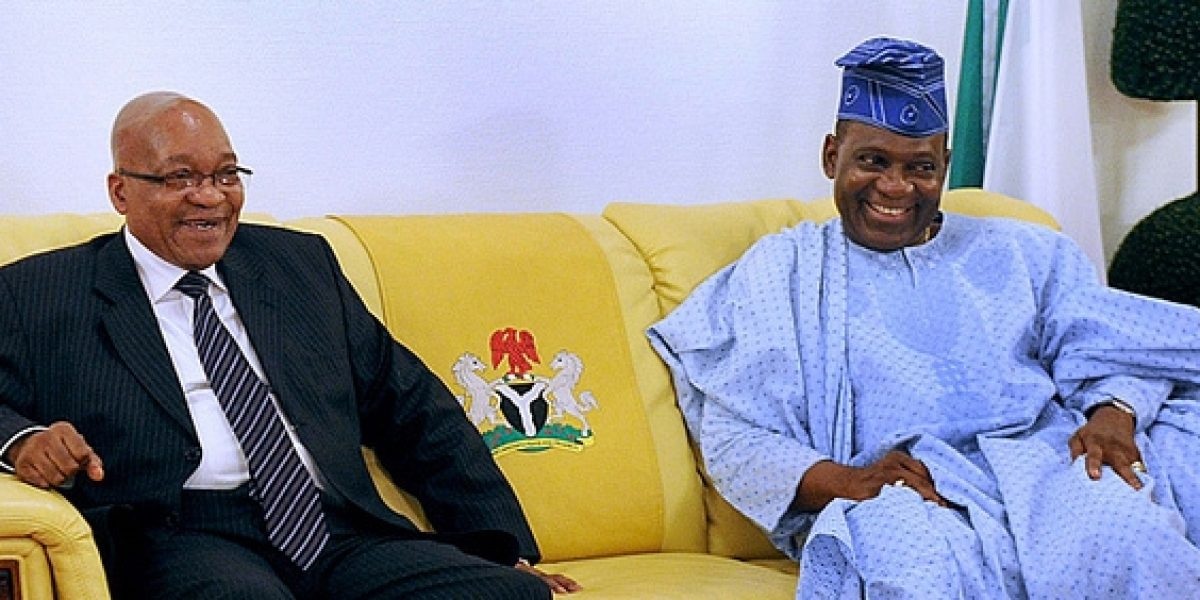

President Zuma’s working visit to Nigeria in April this year, followed by President Jonathan’s state visit to South Africa from 6 to 8 May 2013 is likely to improve the bilateral relationship. But will political leaders in both countries be able to fully seize the opportunity? It is unclear the extent to which either continental giant is prepared to use these reciprocal visits to initiate an entente cordiale. Resetting the button is not only essential for the bilateral relationship, but when Nigeria and South Africa cooperate, they are more likely to deliver continental public goods, including economic development, peace and security.

However, what is required goes beyond quick-fix solutions and the photo-opportunities that will invariably accompany both state visits. Addressing what is wrong in Nigeria-SA relations requires a deeper understanding of the countries’ self-image, their respective motivations and their broad external orientations. There are interesting contrasts in the domestic political environments that determine their foreign policy decisions and outcomes. Paying greater attention to this would enable both parties to manage perennial misunderstandings, tensions and mutual suspicions that have characterised their ties. South Africa’s ruling party, the African National Congress (ANC), was forged through a protracted anti-apartheid struggle that continues to shape Pretoria’s anti-colonialist world-view in relation to western powers and their role in African affairs. By contrast, successive Nigerian rulers since the 1999 political transition have seemingly coveted the legitimising balm which warmer relations with western powers confers on political actions within the contested domestic arena.

More important, while Nigeria’s domestic order has been plagued by chronic instability and security challenges, South Africa’s relative stability over the past decade has provided the country with sufficient political capital to pursue the role of diplomatic spokesperson for Africa. The inclusion of the country in the G20 and the BRICS attest to the successes that Pretoria has achieved in international affairs.

Notwithstanding the stresses emanating from the official strategic and diplomatic agendas, including people-to-people relations, commercial exchanges have strengthened considerably since the democratic transitions in both countries in the 1990s. Following their entry into the Nigerian market from 1999 onwards, more than 100 South African firms now operate in Nigeria. South Africa’s mobile telecommunication giant, MTN, is only one of these that have prospered within Nigeria’s large internal market of 160 million people, servicing highly profitable sectors across banking, retail and media. Also, Nigerian conglomerates such as Oando Plc (listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange) and the Dangote Group (with investments of nearly $400m in cement production in South Africa) have been at the forefront of consolidating commercial ties. Nigeria currently enjoys a surplus in bilateral trade, in large part due to South African oil demand which constitutes 98% of its imports from Nigeria. But there is ample scope for diversifying commercial relations in ways that will more mutually and sustainably benefit both countries.

The strength of the commercial relationship and the potential for deepening economic linkages provide opportunities for a more ambitious bilateral relationship. Nigeria’s economy is poised to overtake that of South Africa by 2018. Still, nothing in the fundamentals of both countries’ relations precludes working together, much as China and India’s rivalry and mutual suspicion has so far not foreclosed the possibility of their joint engagement on regional and global interests. The unique phase marked by the Obasanjo-Mbeki era when both countries were at the helm of a reform agenda for the African continent – most visibly expressed through their joint leadership of the NEPAD initiative created in 2002 – can be replicated. However, in marked contrast to that activist period, both countries’ current presidents are perceived as weak, indecisive leaders whose foreign policy engagement on African issues has lacked the vision that characterised the collaboration in the early 2000s’.

Going forward, there is a need for a more strategic use of the South Africa-Nigeria Bi-National Commission. Its workings and agendas need to be aligned in ways that allow a deeper, more sustained dialogue covering issues of convergence, including the contentious ones. Crucially, the highest levels of political leadership in both countries also need to become more centrally involved in the management of the key irritants in the relations, such as mutual visa regimes, treatment of respective nationals abroad and at main international entry ports as well as in the provision of effective and adequate consular services. The Bi-National Commission should also be used to coordinate in advance issues beyond the bilateral portfolio to include key continental challenges. The prospect of a globally engaged and respected Africa is diminished by the fact that both Abuja and Pretoria have so far failed to craft a mature, interest-based and regular engagement befitting Africa’s two powerhouses. The state visit should serve as a starting point for timely corrective actions that can nurture a bolder and ambitious bilateral relationship.

More SAIIA Research on Nigeria

- Unpacking the South Africa – Nigeria relationship ahead of the AU Summit

Lisa Otto

12 July 2012 - Chinese Business Interest and Banking in Nigeria

By Abiodun Alao

SAIIA Policy Briefing, No 20, July 2010 - Nigeria and the BRICs: Diplomatic, Trade, Cultural and Military Relations

By Abiodun Alao

SAIIA Occasional Paper No 101, November 2011 - Nigeria and the Global Powers: Continuity and Change in Policy and Perceptions

By Abiodun Alao

SAIIA Occasional Paper No 96, October 2011 - Banking in Nigeria and Chinese Economic Diplomacy in Africa

By Abiodun Alao

SAIIA Occasional Paper No 65, July 2010 - Elephants, Ants and Superpowers: Nigeria’s Relations with China

By Gregory Mthembu-Salter

SAIIA Occasional Paper, No 42, September 2009 - Enhancing the Governance of Africa’s Oil Sector

By Douglas Yates

SAIIA Occasional Paper, No 51, November 2009 - Nigeria as an Emerging Economy? Making Sense of Expectations

By David Uchenna Enweremadu

South African Journal of International Affairs

Volume 20.1, 2013 (Subscription required)