Recommendations

- Bold political commitment: Countries should show firm political resolve for the sustainable use of marine resources and highlight success stories internationally.

- Relationships and networks: Trustworthy in-country partners are key for investors. Country platforms or intermediaries can help foster trust, especially where government capacity is limited.

- Capacity building: Clear national plans for the SOE should be backed by strong institutions and trained personnel to implement them.

- Regulatory development: A supportive legal framework is crucial. Reform should focus on transparency, stakeholder engagement and co-management to meet economic, environmental and social goals.

Executive summary

A sustainable ocean economy (SOE) has been identified as an important development pathway for small island developing states (SIDS), yet such states have taken a variety of approaches to implementing an SOE. While national approaches may vary, it is essential that appropriate regulatory and institutional arrangements are put in place to unlock finance flows that can contribute to sustainable, climate-resilient ocean economies. This briefing outlines a range of actions required by state and non-state actors to advance an SOE for SIDS.

Introduction

The SOE, or the sustainable and regenerative blue economy, is identified as a development pathway that would increase economic benefits to SIDS and least developed countries from the sustainable use of marine resources. Target 14.7 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) lists the sustainable management of fisheries, aquaculture and tourism as key sectors for achieving this goal. However, there is no universally agreed-on definition of an SOE and no standardised set of sectors included within it, nor is there a clearly defined pathway for its achievement. This has left considerable flexibility for countries to define an SOE nationally and pursue it in their preferred manner. For the purposes of this brief, an SOE is defined as the use of ocean resources to promote economic growth, improve livelihoods and employment, and preserve the health of ocean ecosystems and associated services, as outlined by the High-Level Panel on Sustainable Ocean Economy. This encompasses marine protection, aquaculture and fisheries, and marine biotechnology, while emphasising that an SOE is concerned not only with which sectors are developing but also with how they are developing. The aspirations of an SOE include governance dimensions such as stakeholder engagement, access to information, increased transparency and accountability, and adaptive management and mechanisms for conflict resolution that result in creating new norms.1Narissa Bax et al., “Towards Incorporation of Blue Carbon in Falkland Islands Marine Spatial Planning: A Multi-Tiered Approach”, Frontiers in Marine Science 9, no. 1 (2022): 2–9; Camilla Novaglio et al., “Deep Aspirations: Towards a Sustainable Offshore Blue Economy”, Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 32, no. 1 (2022): 211–226.

Despite global commitments, the promise of the SOE has not manifested, with progress towards achieving SDG 14 lagging. A lack of finance has been identified as one of the culprits.2UN, Financing for Sustainable Development Report (UN, 2022). Dwindling overseas development assistance and reduced flows of foreign direct investment to SIDS,3UN, Financing for Development of Small Island Developing States (UN, 2024). compounded by losses and damages caused by climate impacts that can wipe out a significant percentage of GDP overnight, contribute to the slow progress.

Existing literature identifies a weak policy and regulatory framework as a barrier to investment and funding to an SOE, particularly in SIDS.4Rashid Sumaila et al., “Financing a Sustainable Ocean Economy”, Nature Communications 12, no. 1 (2021): Article 3259. However, the specific requirements for establishing such an enabling legal environment remain unclear. It has been argued that laws that incentivise investments through the protection of foreign investors, combined with clear property rights, are key.5Rafael La Porta et al., “Investor Protection and Corporate Valuation”, The Journal of Finance 57, no. 3 (2002): 1 149–1 169. However, such arguments tend to focus only on foreign direct investment. Funders and investors in an SOE include more than traditional investors; in recent years, new financing mechanisms such as debt-for-nature swaps and blue bonds have emerged. There are other motivations and interests for such investors, such as environmental and social outcomes in addition to financial returns. Hence, laws on the management of natural resources and laws that facilitate and incentivise social enterprise are also identified as important.6UN Development Programme, “Social and Environmental Standards” (Policy Update, UNDP, 2021); Ryan Whisnant and Antonia Reyes, Blue Economy for Business in East Asia: Towards an Integrated Understanding of Blue Economy (Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia, 2015). Despite the continued emphasis on creating an enabling legal environment to support foreign investment, this brief shows that such a framework alone would be insufficient to attract investors and funders of the SOE; additional measures are required.

Based on interviews with government officials from SIDS and a survey of 13 investors and donors who fund and/or invest in an SOE in SIDS, the main determinants of funding and investment decisions were identified as:

- location and environment;

- political will;

- track record of commitment to the preservation of the marine environment; institutional arrangements for ocean affairs; and

- trusted in-country partners.

The investors and funders recognised that the legal framework is a determinant of investment decisions, albeit not a primary one. This briefing argues that it is the combination of all the abovementioned factors, together with a clear legal framework, that creates an attractive environment for investing in the SOE.

African small island developing states

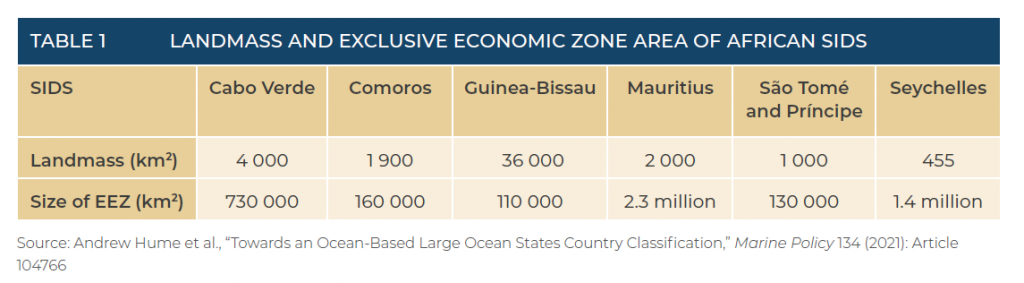

African SIDS are scattered across the Indian and Atlantic oceans. They comprise Comoros, Mauritius and Seychelles in the former and Cabo Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe and Guinea-Bissau in the latter. Their similarities include their small landmasses and populations, vulnerability to external economic and climatic shocks and, in relation to their landmass, extremely large exclusive economic zones (EEZs) (see Table 1), making them heavily dependent on ocean-related economic activities.

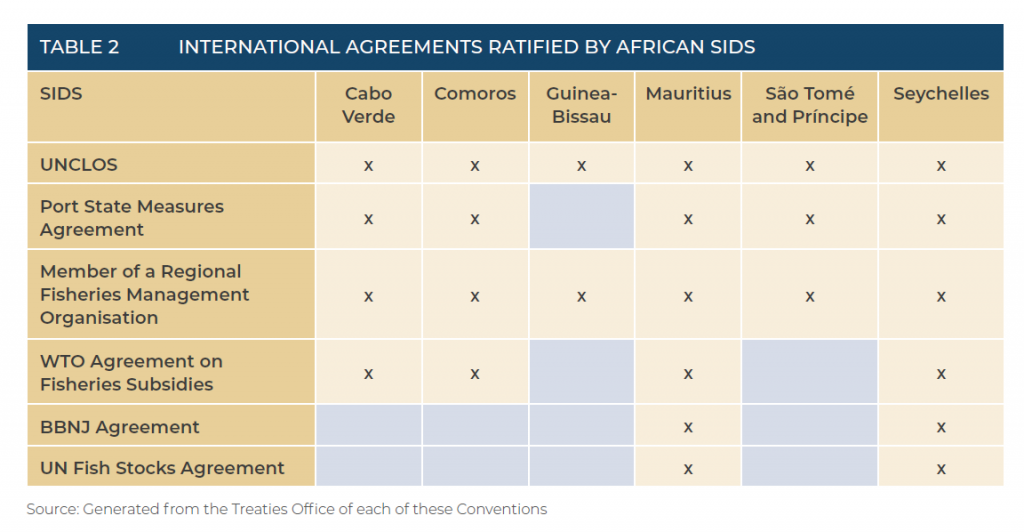

The vast resources within the maritime domains of these island states present an opportunity to develop an SOE, including through sectors such as marine protection, fisheries, aquaculture and marine biotechnology. However, while traditional sectors in the SOE are well used, emerging industries such as sustainable aquaculture and marine biotechnology remain on a small scale or are merely aspirational. Table 2 depicts the development of the different sectors underway in the six SIDS.

Political will

Of the six African SIDS, Seychelles, Mauritius and Cabo Verde have prioritised the inclusion of the sustainable management of the ocean in their policy agendas. In 2024, at the 79th UN General Assembly, Seychelles highlighted its ocean leadership by showcasing its use of nature-based solutions to combat climate change and its issuance of blue bonds to harness capital markets in support of the sustainable use of marine resources. All three SIDS emphasised the importance of the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Agreement. Seychelles and Mauritius highlighted that they had ratified the BBNJ Agreement and called for other states to do so too. This sentiment was echoed by Cabo Verde, which also pointed to its leadership as a patron of the Ocean Decade Alliance from 2021–2023 and its upcoming hosting of the fifth UN SIDS conference.

There are similarities and differences in the ratification of ocean-related agreements among African SIDS (Table 2) depicting the political and legal commitment to ocean governance. While all six SIDS are state parties to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, Mauritius and Seychelles have ratified its implementing agreements and led the way in the ratification of the BBNJ Agreement. Across both the Indian and Atlantic oceans, tuna remains a prized resource for small island economies. Therefore, despite not all SIDS being party to the UN Fish Stocks Agreement, all are members of tuna-focused regional fisheries management organisations. On the other hand, Guinea-Bissau stands out as the only African SIDS that has not ratified the Port State Measures Agreement, while neither Guinea-Bissau nor São Tomé and Príncipe has ratified the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies.

Track record of commitment to the preservation of the marine environment

SIDS are often described as stewards of the ocean because of the vast oceanic resources that fall under their custodianship. The indicators used to display a track record on the preservation of the marine environment include whether a country has formally committed to the 30×30 global campaign (an effort to ensure that 30% of ecosystems are protected by 2030) and the current percentage of its EEZ that is protected. On the one hand, we see that Cabo Verde, Comoros, Guinea-Bissau and Seychelles have committed to the 30×30 campaign. On the other hand, actual protection remains minimal: Cabo Verde, Comoros, Mauritius and São Tomé and Príncipe have protected less than 1% of their EEZ through the establishment of marine reserves, based on the World Database on Protected Areas.7UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Protected Area Profile from the World Database on Protected Areas (UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, 2025). This provides an opportunity for funders to support countries to reach the 30% target. For example, in 2015, Seychelles had less than 1% of its EEZ protected, but with the support of a $21,6 million debt-for-nature swap, the country now protects 33% of its EEZ. A more recent example is the debt-for-nature swap between Cabo Verde and Portugal that supports nature and climate goals concluded in 2023.8Governo de Cabo, “Cape Verde and Portugal Sign Agreement to Convert Debt into Investment in the Climate and Environmental Fund”, Governo de Cabo, June 20, 2023.

Institutional arrangement for managing ocean affairs

The SIDS that have pursued an SOE globally have not opted for a uniform institutional arrangement for the coordination of ocean affairs.9Michelle Voyer, Dominique Benzaken and Constance Rambourg, “Institutionalizing the Blue Economy: An Examination of Variations and Consistencies among Commonwealth Countries”, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 377 1854 (2022): 20210125–20210125. Different models are available, including the formalisation of a unit or department under a ministry dedicated to the blue economy, as seen in Seychelles, and a looser arrangement that brings together multi-sectoral ministries, as in the case of Fiji. Interestingly, African SIDS have preferred a formalised approach, with four of the six SIDS having ministries responsible for the blue economy. Such blue economy ministries tend to be coordination units across multiple sectors in the blue economy. In 2022, São Tomé and Príncipe codified its strategy on the blue economy into law, formalising the creation of the Strategic Intelligence Unit for the Blue Economy, a coordination committee and a commission charged with the coordination, monitoring and evaluation of financial and technical partners supporting the transition towards the blue economy.10World Bank, Charting a Blue Course – Investment Projects for the Blue Economy Transition in São Tomé e Príncipe (World Bank, 2023).

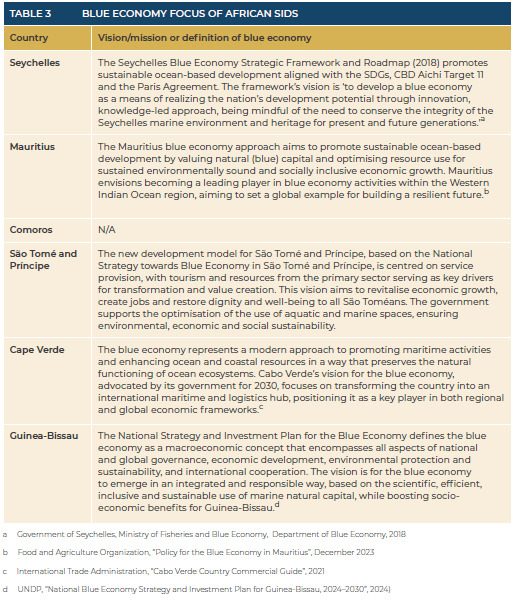

The work of these departments, units and ministries is guided by policies. Five of the six African SIDS have policies on the development of the blue economy. Table 3 shows that all the policies highlight the need to utilise the blue economy for economic prosperity while simultaneously ensuring environmental sustainability. The actual operationalisation of such visions is not always straightforward, but an appropriate regulatory framework can help facilitate this.

Regulatory framework

Only one African SIDS has elevated its policy instrument to the status of law, but it is unclear how this is being operationalised across the various sectors of the SOE. An enabling legal environment is recognised as critical to realising an SOE, but what such an environment actually consists of is unclear. A review of regulatory frameworks across three SIDS found that, even among those attracting significant funding to the SOE, regulatory approaches vary, suggesting that no fixed set of laws is required to secure investment. Nevertheless, there were some similarities, including incentives to invest in the SOE, such as tax breaks for mariculture and/or aquaculture investments, and the existence of anti-money laundering, anti-bribery and counter-terrorism financing laws that provide safeguards for investors. However, in some instances, laws alone are insufficient to attract investment when there are significant gaps in the infrastructure and skills needed to develop emerging sectors of the SOE.

As previously highlighted, an SOE requires investment approaches that consider not only financial returns but also environmental and social impacts. However, there is no strict requirement for dedicated laws to be in place before a deal is closed to ensure such impacts are addressed. A good example of this is the Seychelles blue bond issued in 2018, where funds for aquaculture projects could not be disbursed until relevant regulations were enacted.11Dominique Benzaken et al., “From Concept to Practice: Financing Sustainable Blue Economy in Small Island Developing States: Lessons Learnt from the Seychelles Experience,” Frontiers in Political Science 4 (2024): Article 1040318. While natural resource management laws may be introduced after an investment deal is concluded, investors and funders still need reassurance that governments are committed to their implementation, even if delayed. Such reassurance can come from strong partnerships with the government and trusted supporting institutions.

For an SOE, finance is not the destination. Its objectives and aspirations cannot be achieved solely through incoming financial flows; they must also lead to positive environmental and social outcomes. Regulatory frameworks can help deliver these outcomes by mainstreaming the following principles:

- stakeholder consultation;

- transparency;

- co-management of natural resources;

- adaptive management;

- cross-sectoral conflict resolution; and

- policy coherence and coordination.

Conclusion

SIDS depend on external financial resources to develop their SOE. Therefore, understanding what motivates investors and funders is essential to guide national priorities. Governments should demonstrate bold political commitment, establish clear plans and institutional frameworks and take concrete steps to translate vision into action.

An SOE often attracts non-traditional funders and innovative financing mechanisms, such as blended finance, which may require enabling legislation – for example, accession to the New York Convention on Arbitration to facilitate dispute resolution. Other laws that promote positive environmental and social outcomes should not be considered an afterthought; rather, they should be embedded within deals as core deliverables, helping to build momentum for broader legislative reforms.