The BRICS countries – Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa – collaborate in a number of areas and have emerged as a forceful voice for global governance reform. But with their lukewarm cooperation on COVID-19 vaccines, they have missed an important opportunity to demonstrate their ability to mount a strong collective response to a global crisis.

The pandemic has hit the BRICS hard. India has recorded the highest number of infections within the group (and the second most globally, after the United States), with 32.2 million at the time of writing. Brazil has reported 20.3 million cases, Russia 6.6 million, South Africa 2.6 million, and China – where the pandemic originated – fewer than 100,000. Total COVID-19 deaths across the five countries now stand at 1.25 million, with Brazil and India accounting for 80% of these.

This heavy toll – and the fact that the rich countries of the G7 have purchased over one-third of the world’s COVID-19 vaccine supply, despite accounting for only 13% of the global population – should have provided an impetus for stronger cooperation among the BRICS countries. But as the University of the Witwatersrand’s Vishwas Satgar noted recently during a webinar hosted by the BRICS Policy Center, the BRICS “have seen a divergence, inconsistency, and lack of cooperation on COVID-19 vaccination.”

The BRICS countries are not new to so-called “vaccine diplomacy,” or efforts to strengthen ties through cooperation in vaccine-related research and innovation. During South Africa’s presidency of the bloc in 2018, for example, its government proposed establishing a joint Vaccine Research Center – an idea that became part of the BRICS’ Johannesburg Declaration.

Although the center has yet to materialize, there were hopes that the BRICS would work together closely on COVID-19 vaccine development and distribution. But even some of the vaccines developed by BRICS countries themselves have received a mixed reception within the bloc.

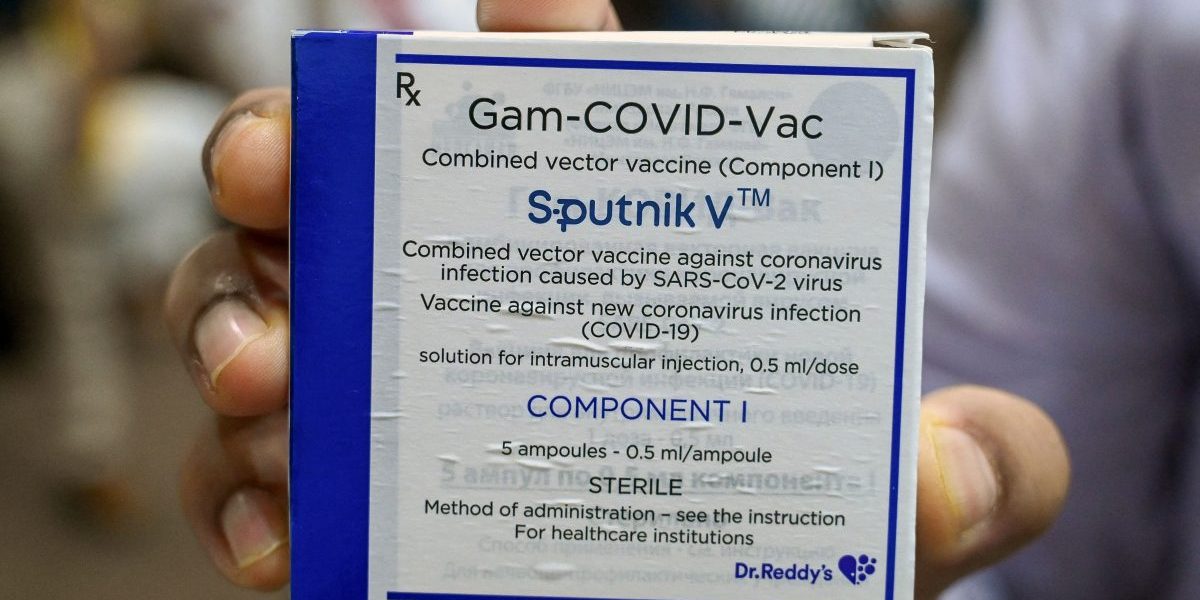

In August 2020, Russia became the first country in the world to register a COVID-19 vaccine candidate, and three months later, it became the first among the BRICS to announce a high-efficacy vaccine: Sputnik V. The vaccine is reportedly 92% effective against the coronavirus. But scientists have criticized the rapidity of the Sputnik V trials and lack of transparency regarding the raw data, and the World Health Organization has yet to approve the vaccine.

Among the other BRICS countries, the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency initially blocked Sputnik V in response to data indicating adverse side effects. It reversed this decision in June 2021 and allowed the import of 928,000 doses. India received 125 million doses of the vaccine in May 2021.

The South African Health Products Regulatory Authority has not approved Sputnik V for use and is awaiting further data from the Russian Gamaleya Research Institute, which developed the vaccine. Although SAHPRA is coming under increasing pressure from the left-wing Economic Freedom Fighters party to approve “non-Western” COVID-19 vaccines, the agency remains steadfast in its science-based approach free of political influence or pressure.

In contrast, the WHO granted the Chinese Sinopharm and Sinovac vaccines emergency-use listings in May and June 2021, respectively. Brazil participated in Sinovac trials and, following positive results, has continued to use this vaccine. But although the Drugs Controller General of India announced in June that WHO-approved COVID-19 vaccines will no longer require post-approval bridging trials and batch testing in India, it is unclear whether the country will include the Sinovac and Sinopharm vaccines in its immunization program. Likewise, South Africa gave the Sinovac vaccine the green light for use in July 2021, but has yet to announce any procurement plans.

Then there is vaccine manufacturing. India accounts for 50% of all global vaccine supplies, and the Serum Institute of India – the world’s largest vaccine producer – has worked with the Oxford Vaccine Group to produce Covishield, a local version of the AstraZeneca-Oxford COVID-19 vaccine. But despite its vaccine-production might, India has fully vaccinated only 8.8% of its population against COVID-19, while 22% have received one dose.

Similarly, the Cape Town-based Biovac company will start manufacturing the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in 2022 for distribution within Africa. Currently, just 6.9% of South Africans are fully vaccinated against COVID-19, and a further 5.6% have received one dose. Biovac would become a “fill-and-finish facility” before vaccines make their way to their intended destinations.

The Indian and South African vaccine producers have entered technology-centered agreements with their Western partners, but do not own any COVID-19-related patents. In an attempt to address this issue, even before concluding these agreements, the two countries’ governments led a push at the World Trade Organization in October 2020 to waive intellectual-property rights for COVID-19 technologies and vaccines.

But BRICS foreign ministers did not collectively support this proposal until June 2021, eight months after it was first submitted. China and Russia had previously remained silent on the issue, while Brazil, as BRICS expert Karin Costa Vazquez notes, was the only member of the group openly to oppose this idea, in direct alignment with former US President Donald Trump. Brazil’s position became more supportive only in early 2021, after India said it would start sending COVID-19 vaccines to key partner countries, and US President Joe Biden’s administration announced its support for the proposed IP waiver.

For now, India and South Africa’s role in manufacturing COVID-19 vaccines must not distract them from pursuing their important proposal at the WTO. In addition, the BRICS countries should prioritize the establishment of the Vaccine Research Center in order to enhance cooperation in this domain.

Whether they will succeed remains to be seen. The COVID-19 pandemic has tested the BRICS countries’ collective strength, and found them largely wanting. The bloc has therefore missed a chance to bolster its advocacy of international governance reform, and cast doubt on its fitness for purpose in responding to arising critical global challenges.