When G20 leaders met in London this April the western financial system teetered on the brink of the abyss. Now, days before the third G20 leaders’ meeting in ten months, at Pittsburgh, the Governors of the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England have purportedly declared the recession over.

If correct, Mr Bernanke should take most of the accolades for this tidal shift. However, G20 leaders and, more importantly, their Finance Ministers and Central Bank governors, are an indispensible supporting act. Starting in Washington in November last year, continuing through the London summit and beyond, they have stitched together an impressive list of reforms to global finance whilst ensuring its wheels continued to turn through provision of huge amounts of credit.

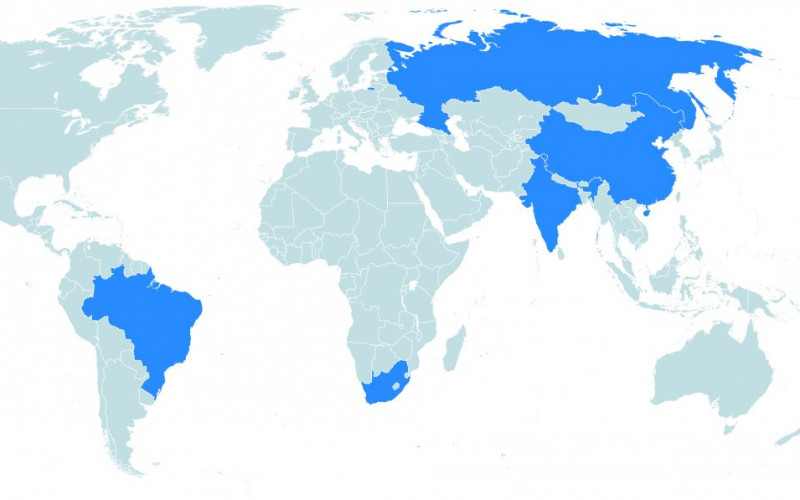

For the emerging economies in the G20 a big challenge is ensuring the group’s agenda remains relevant to them beyond the crisis. For example, the issue of bankers’ compensation, whilst important, is hardly at the centre of the crisis. It is largely a matter for G7 politicians and their electorates; yet in advance of Pittsburgh it has stolen centre stage due largely to its emotive nature. However emerging economies are hardly unified: Brazil, Russia, India, and China have formerly constituted a “BRIC” grouping within the G20 framework so it is not obvious that we can rely on them to support an SA agenda. This raises interesting questions about our alliance choices: perhaps we have more in common with middle powers like Argentina, Mexico, Indonesia, South Korea, and Australia?

The major challenge now lies in coordinating “exit strategies” from monetary and fiscal stimuli. As G20 countries are at very different stages in their economic cycles this will prove challenging. For example with economic growth in India resuming, inflation is their main concern. But if they unilaterally increase interest rates whilst the major Western economies keep theirs at historic lows, capital will flood into India causing currency appreciation and generating pressures to devalue, which could spawn trade tensions. So some degree of coordination concerning the sequencing of exit strategies is necessary, and a major test of the G20’s efficacy.

Hence there is now strong rhetorical commitment to the need for the IMF to conduct comprehensive surveillance of the global financial system with a view to pressuring G20 governments to address emerging macroeconomic imbalances such as those which preceded and fed this crisis. The crisis also highlighted the need for a global lender of last resort, which the IMF fulfilled with strong G20 support. Overall, the IMF is the big winner in the G20 process.

But the IMF’s “victory” is fragile in the medium-term. Asians are dissatisfied with the IMF’s apparent favouring of Eastern European crisis countries through allowing conditionalities applied to the latter’s loans to lapse, whereas Asian countries hit by the Asian financial crisis ten years ago did not enjoy such treatment. This resentment, and associated lack of trust in the IMF fuelled a logical Asian reaction: accumulation of massive foreign currency reserves through maintenance of currency pegs to the US dollar, as insurance against future crises. Those reserves were recycled through the US financial system and played a major role in precipitating the current crisis.

The currency pegs, on the other hand, have generated major tensions in the global trading system and play some, albeit unmeasured, role in current tensions concerning protectionism. Since there is no international forum for mediating currency disputes, some have argued that the latter should be taken to the World Trade Organization’s binding dispute settlement mechanism. But the WTO faces its own major challenges, not least bedding down the Doha Round. The G20 Leaders’ meeting is not going to solve that problem; whereas introducing currency disputes into the WTO would run the distinct danger of overburdening it at a delicate time in its history.

Hence the IMF’s role in macroeconomic surveillance is crucial. But if its legitimacy deficit is not decisively addressed, global macroeconomic imbalances are likely to rebuild as stimulus packages are unwound. So if the IMF is to evolve into an effective enforcement mechanism, albeit one without teeth, its governance arrangements have to be overhauled and emerging economy, especially Asian, representation enhanced.

Longstanding African demands for an overhaul of the IMF’s governance arrangements and more flexible conditionalities are favoured by these developments. But it remains to be seen how African representation, including SA, will be affected since collectively we comprise a marginal share of the global economy. So for narrow selfish reasons and also because we purport to represent continental interests in the G20; Pretoria’s economic diplomacy at Pittsburgh and beyond needs to be especially sharp.

What agenda should SA take into Pittsburgh? Most of our objectives are in the process of being obtained, so the first priority should be to ensure that the multitude of work to reform the global financial system initiated by the G20 continues and reaches satisfactory conclusions. Of particular relevance here is ensuring funds earmarked for African economies in distress are delivered on time and without conditions providing such countries pre-qualify on the basis of objective governance criteria. Second, reform of the IMF must be supported, whilst ensuring African representation is maintained and extended. Third, the new institutional arrangements for governing global finance must be bedded down and their work programmes concluded. Finally, Pretoria should reaffirm that it will not introduce any new protectionist measures notwithstanding its G20 counterparts’ evident violations of this promise, except where other countries introduction of such measures seriously prejudices our own trade interests.

Finally, the SA government and its institutions could do a better job of communicating the positions it is taking on the rather lengthy G20 agenda. For example, where does Pretoria stand on: the Chinese currency issue; the extent and depth of IMF surveillance; and the host of issues concerning regulation of the financial sector? A more active engagement with SA business, think-tanks and civil society on these issues would both supplement stretched government resources and promote wider understanding of these fundamental issues of our time.