The current system has enabled many countries to develop, the most notable example being China; yet, the rules have often been skewed against poorer countries. The Washington Consensus was inimical to many countries, while great power interventions in Africa and the Middle East have exacerbated already acute problems. One only has to look at Libya after the fall of Gaddafi.

As a number of developing economies have built up more economic and political power, we have seen the emergence of new forums to address themes that they feel existing multilateral institutions are not tackling sufficiently or that through their creation gives them more independence in determining priorities. The BRICS established the New Development Bank and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement to support, in conjunction with the IMF, members’ balance of payments problems. Led by China, the development finance landscape has also been augmented by the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. None of these institutions are intended at this stage to replace existing ones. They complement them, but they can equally be the foundation of a new alternative hierarchy of global institutions in the future. What they are not yet, is a developed alternative order governed by a different set of principles. Even more importantly, they are not tackling the ‘new international governance’ challenges such as artificial intelligence, the digital economy, and cyber.

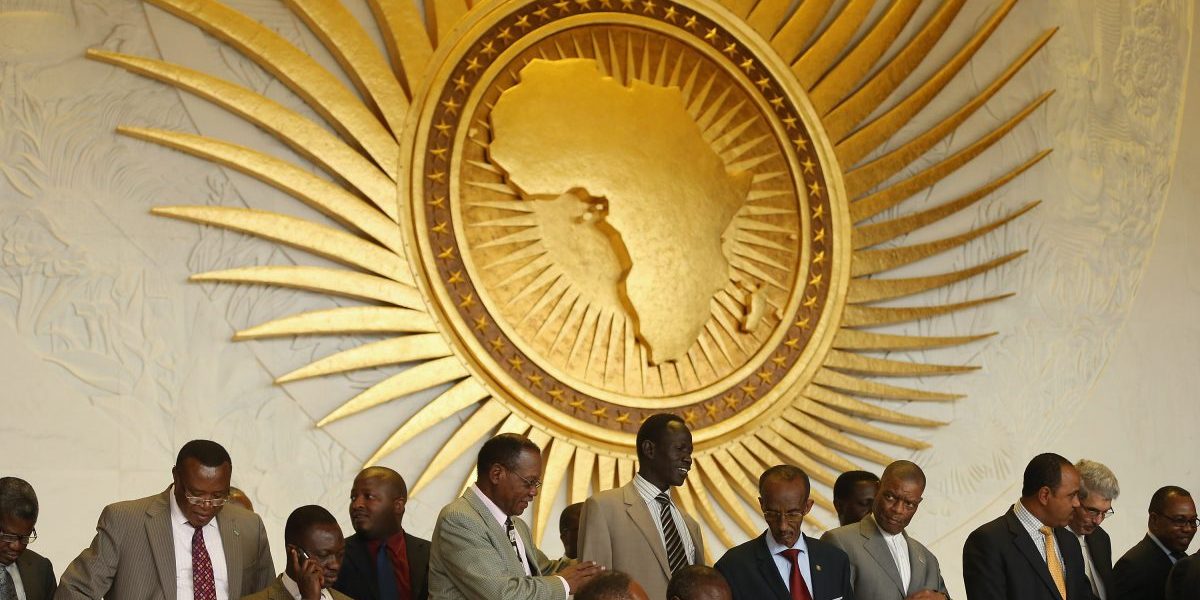

The growing differentiation between the big emerging economies such as China and those in Africa requires that the process of sustaining and reforming multilateralism must also include a strong African voice. After all, Africa has been strongly invested in the system of multilateralism, contributing to the development of global norms, one of the most notable being the ‘responsibility to protect’. Ironically, it was in Libya in 2011 that this norm was significantly subverted.

What options does Africa have?

One of its most powerful tools is that of legitimacy. As a continent that has been marginalised for too long, but with about a quarter of the world’s countries and more than a billion population, Africa in the 21st century cannot be sidelined in any ‘new order’ discussions if their outcomes are to be considered legitimate and representative.

African countries working together through the African Union will need to develop a set of guidelines and principles for their engagement and advocacy. In addition different forums require the development of different strategies of engagement.

They should not shrink from becoming involved in both formal and informal discussions, multilateral and club forums on both old and new governance issues: absent a war where the victors impose their order, the new rules of the game will evolve not only in the structured and formal institutions, but outside them. Africa needs to be at the table and geared to participate. This Africa should consciously enter into debates around norms and standards occurring in the plurilateral realm, for fear that in a world where approaches become regionalised, the continent may end up being a perpetual rule-taker. Key regional African countries have a role to play here.

Lastly, African states and the AU should explore coalitions with other regions and constellations of states that share similar approaches to particular global governance problems, but also values. Depending on the issue, these partnerships may take different forms and include various players, not only states. The world’s governance complexity in the 21st century means that solutions and new institutions will have to be multi-actor, not Westphalian-centric.