Anyone with some money to invest is clearly putting it into property in this growing urban centre. Construction can be a good sign in a developing country. Not only does it provide employment in the short term but infrastructure development supports the growth of other economic sectors in the long-run. While some may argue that property is a safe bet in an uncertain economy, the boom in construction in Ethiopia is mainly driven by infrastructure development objectives.

Government currently devotes $1.3 billion annually to infrastructure, which is 10% of its GDP. As a share of GDP, Ethiopia’s spending on infrastructure is by far the highest on the continent. At a more basic human level it is a sign of optimism and hope for the future.

Ethiopia has ambitious plans to improve the infrastructure available for its 85 million people. There are large power plants being built by Chinese and European companies. The Growth and Transformation Plan sees energy and transport infrastructure as priorities. The energy sector presents the greatest infrastructural challenge to Ethiopia. 8700 megawatts of generating plant will be required over the next decade. This is double Ethiopia’s current capacity.

In transport, there is a need to improve Ethiopia’s poor rural accessibility and ensure that recent investments in roads receive efficient maintenance. Better roads to link Ethiopia to Mombasa and Port Sudan are planned. This would reduce reliance on Djibouti for access to the sea and the movement of many goods in and out of the country.

In terms of air transport, Ethiopia is a regional leader. Its national airline is one of Africa’s three top international carriers, and they have an extensive network across Africa and an excellent safety record. In sharp contrast, however, Ethiopia’s rail transport requires major rehabilitation. The rail corridor between Addis Ababa and the Port of Djibouti has deteriorated and fallen into disuse. With the on-going conflict with Eritrea in mind, diversification of options for accessing the sea is important for landlocked Ethiopia.

Looking up from the south of the African continent, we usually perceive Kenya as the driver or anchor economy of the East African region. This reflects in part a much closer economic relationship between South Africa and Kenya relative to Ethiopia (as well as its partners in the East African Community – Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda). Kenya also has a more open, diverse and vibrant economy than Ethiopia. According to the World Economic Forum’s latest global competitiveness index, Ethiopia ranks 129th out of 142 countries in terms of business sophistication.

This is relative to Kenya’s impressive 59th rank out of 142 countries. Kenya’s top three troubling factors for doing business include corruption, access to finance and inadequate infrastructure.

On the contrary, Ethiopia’s top three troubling factors for doing business are arguably more fundamental. They include access to finance, foreign currency regulations and inflation. Furthermore, Kenya’s relatively democratic political system also differs from its more restrictive neighbour to the north.

From a perspective even more removed, the US State Department has identified Ethiopia as one of the most strategic players in Africa. This was reflected recently in the invitation extended to Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi to attend the G8 Summit hosted by America at Cape David as one of only a handful of African representatives.

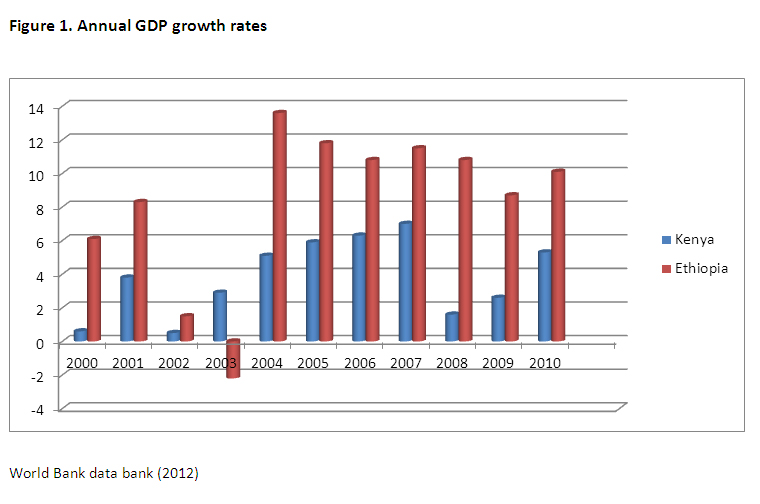

While the security motivations cannot be underestimated, there are also economic factors in moving in Ethiopia’s favour. Recent statistics show strong signs of growth in Ethiopia with Kenya slowing down (see figure 1). Investments on growth enhancing sectors such as infrastructure and social sectors have been the basis of Ethiopia’s impressive growth rates since 2005/06.

Like Nigeria, Ethiopia has the blessing and curse of a large population. By 2040 Africa will be home to the world’s largest working population. If harnessed properly then people can be a true asset. This will however require significant liberalisation of the Ethiopian economy and strengthening of the private sector. The kind of liberalisation required will have to be strategic and complement Ethiopia’s industrial aspirations.

In June 2011 the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) negotiations were launched in South Africa with the aim of bringing together the three regional economic communities of SADC, COMESA and the EAC. Ethiopia is a member of COMESA but is yet to fully implement the free trade agreement (FTA) in that region. One of the reasons Ethiopia refused to join the COMESA FTA was that they wished to protect their manufacturing sector against unfair regional competition from regional players like Kenya.

A recent study by COMESA has found however that despite not signing the FTA, the manufacturing sector has remained uncompetitive. The manufacturing sector in Ethiopia contributes less than 10 percent of the total value of merchandise exports, while the proportion of persons engaged in industry and related activities accounts for less than five per cent of the workforce

While much of the speculation to date in the TFTA negotiations has focused on the economies of South Africa, Kenya and Egypt, it would not be wise to neglect those larger countries that are within the area envisaged to be covered.

South Africa would do well to develop a deeper understanding of the views of Ethiopia and its likely approach to trade negotiations as well as regional integration. Ethiopia deserves to be looked at as a potential regional powerhouse and we overlook it at our own peril.