From 27-28 August, TICAD will be held for the first time in an African country. This milestone reflects the evolving nature of relations between Japan and the continent, and the more assertive and confident agency of African countries in their interactions with external powers.

TICAD was originally established to reframe Japan’s aid policy after the end of the Cold War. In the ensuing years Africa has seen a proliferation of forums for engagement with China, India, the EU, Korea and Turkey, to name but a few.

For all the touted ‘first-mover’ advantage, Tokyo’s initiative and its aid and economic activities in Africa have not received the same profile as some of the other forums, most notably China’s Forum on China-Africa Cooperation.

From 1993 to 2013 TICAD was held every five years in Japan. While led by Japan, it has included the African Union (AU) Commission, and international organisations as co-ordinating partners. TICAD supported the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) after it was adopted as the socio-economic programme of the continent, and the special relationship is evident in the fact that the NEPAD Agency and the AU continue to be the focal point for Africa’s engagement with Japan.

Although Japan’s TICAD initiative started off as an articulation of its post-Cold War aid policy, over the years it has increasingly also incorporated trade and investment dimensions, largely in response to African countries’ calls in this regard.

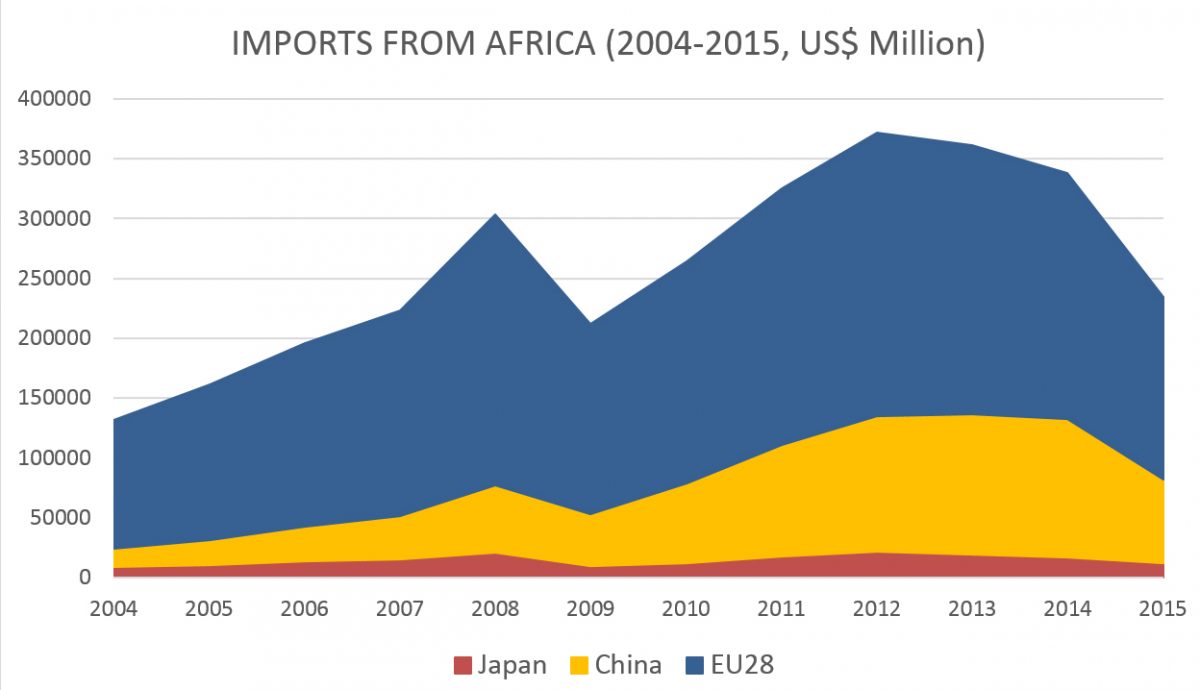

Japan was until recently the world’s second largest economy; yet its overall trade with Africa in 2015 was US$20 billion, compared to China’s which was US$180 billion.

Japanese direct investment in Africa grew from US$1.7 billion in 2005 to about US$10.5 billion in 2014.

Although Japan is a member of the OECD-DAC its aid is differentiated from that of other ‘Western’ donors. Its focus on infrastructure and low-key (if any at all) political conditionality is more reminiscent of emerging powers. Yet, it has not benefited among African countries from this fact at the political level. It has been seen as part of the West, and China’s strong diplomatic outreach to Africa with its emphasis on South-South has made a greater impact since 2000.

This year’s TICAD will be attended by some 35 African heads of state, and will also include a sizeable Japanese business contingent and a business fair. Japanese officials believe this initiative is an important means to expose their business people to the African business environment and enable them to meet and interact with African governments.

In another indication of the shift away from aid as the focal point of the relationship, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has established a Conference on African Economic Strategy through his office which acts as the co-ordinating mechanism for all ministries, thus emphasising that relations with Africa have a strong economic focus and are not solely defined by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This is an important shift in emphasis for Africa and signals a maturing relationship and aspiration to place Japanese–African relations on a different footing.

While the India–Africa Forum Summit has moved from a three-yearly event to intervals of five years, TICAD is going in the opposite direction, a decision taken at the 2013 TICAD summit. The 2013 summit also established a follow-up mechanism to review and assess, on an annual basis, the implementation of the commitments in the Yokohama Action Plan.

At TICAD V in Yokohama, Japan committed US$32 billion of public and private funds, including US$14 billion in overseas development aid over the next five years. Infrastructure has also been an important dimension of Japanese assistance to Africa and in 2013 it committed about US$6.5 billion in loans for infrastructure. In addition, there were commitments made in health, education, environment, trade and investment, agriculture and human resources. Japan committed US$500 million to train 120,000 health workers to provide universal health care and US$500 million in co-financing with the African Development Bank for the African private sector. Moreover, in August this year Japan committed US$120 million in aid to help counter-terrorism efforts in Africa. To aid its anti-piracy efforts in the Horn, Japan has a base in Djibouti, its first overseas base since the end of the Second World War, which it opened in 2011.

The Summit in Nairobi is part of a bigger offensive to market Japan’s presence and assistance on the continent as Africa continues to be seen as the next frontier market with significant opportunities.

One should also not lose sight of the fact that Japan’s engagement with Africa is part of its geopolitical positioning in a changing global environment. This includes Japan’s ongoing desire to see UN Security Council reform, including a permanent seat in recognition of its ongoing significant support to the UN and its operations. The world in 2016 is a very different place since TICAD was established in 1993.

Since TICAD I, China has overtaken Japan as the world’s second largest economy. Under President Xi Jinping, China is flexing its muscles in its region, especially around maritime disputes in the South China and East China seas. While Africa has no ‘dog in the fight’, both countries have an interest in garnering international support for their positions on the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands in the East China Sea. In recent years Japan has taken steps to reverse its post-war pacifist constitution, and in 2014 prime minister Abe ended Japan’s self-imposed ban on the export of weapons. Escalation in the tensions in the East China Sea is likely to have an impact on the world economy and maritime trade.

Will African countries be drawn into taking positions on Asia’s maritime disputes? In this China probably still holds the advantage, built on the diplomatic capital it has amassed over many years. However, it is in the continent’s interests to continue to support the observance of international law and respect and strengthening of multilateral frameworks. In Nairobi though, the discussions are likely to focus on Africa’s developmental priorities and an assessment of progress on TICAD since 2013. Moreover, Japan is recognised as a pragmatic partner and African countries should not be surprised to see functional cooperation emerging between China and Japan, particularly in the infrastructure space where both countries enjoy strong comparative advantages.

The interest from so many eligible suitors has been an ideal environment for African states to maximise their leverage on investment, infrastructure projects and the like. As the Kenyan foreign affairs and international trade Cabinet Secretary Amina Mohamed said recently, ‘Everybody is competing in the same space. And if there is no competition, there is a problem. It simply allows us to choose the best.’