Recommendations

- Establish a cross-sectoral committee or working group in the AU Peace and Security Department, the AU Infrastructure and Energy Development Department and the AUDA-NEPAD to ensure that conflict-sensitive AU infrastructure policies and programmes are developed and implemented explicitly under PIDA PAP 2.

- Draft PIDA ToRs and/or templates for infrastructure project implementation in FCAS to be applied under the SDM, including tools and guidelines to assist project developers in building practical P&S provisions into the project lifecycle.

- Establish a knowledge centre for infrastructure development in FCAS hosted within the AUDA-NEPAD, as part of the current AUDA-NEPAD and OECD collaboration, to act as a repository for existing regional evidence on peace, security and infrastructure development, commission future studies, and host dialogues and training to build regional capacity.

Executive summary

The AU’s Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA) has an ambitious agenda to connect and integrate the continent through hard and soft infrastructure. The current PIDA Priority Action Plan 2 (PIDA PAP 2) prioritises 69 regional projects. One of the challenges in African infrastructure development that does not get enough attention is the complexity of working in conflict and post-conflict environments. Over half of the 39 countries currently classified as fragile and conflict-affected states (FCAS) are African. It is therefore important to understand how PIDA infrastructure policy, planning and implementation can be designed to maximise positive impacts on peace and security (P&S) and mitigate the risk of conflict hindering the traditional economic benefits of regional infrastructure in FCAS. This policy brief seeks to analyse global and African literature and best practices on infrastructure development and P&S to see whether sufficient linkages have been drawn between infrastructure and P&S in AU and PIDA strategies. Recommendations target the improved integration of P&S considerations in continental infrastructure development strategies to maximise project success and contributions to peacebuilding.

Introduction

The AU’s Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA) sets out an ambitious agenda to connect and integrate the African continent through hard and soft infrastructure. PIDA implementation is led by the AU Development Agency (AUDA-NEPAD) and phased in 10-year PIDA Priority Action Plans (PIDA PAPs), comprising strategically important projects proposed by regional economic communities (RECs) and AU member states. The PIDA PAP 1 (2012–2020) comprised 51 regional programmes and over 400 individual projects planned for 2012–2020. PIDA PAP 2 (2021–2030) consists of a more streamlined list of 69 priority regional projects. Completing PIDA infrastructure projects is critical to enabling continental development initiatives such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which aims to integrate African markets into a single free trade area and requires hard and soft infrastructure to move goods across the continent efficiently. To this end, an AU infrastructure fund is currently being established to help to bridge the $60–90 billion continental infrastructure gap and support the AfCFTA.1Reuters, “AU to Set Up Infrastructure Fund to Make Free Trade Plans a Reality”, Sunday Times, February 19, 2021.

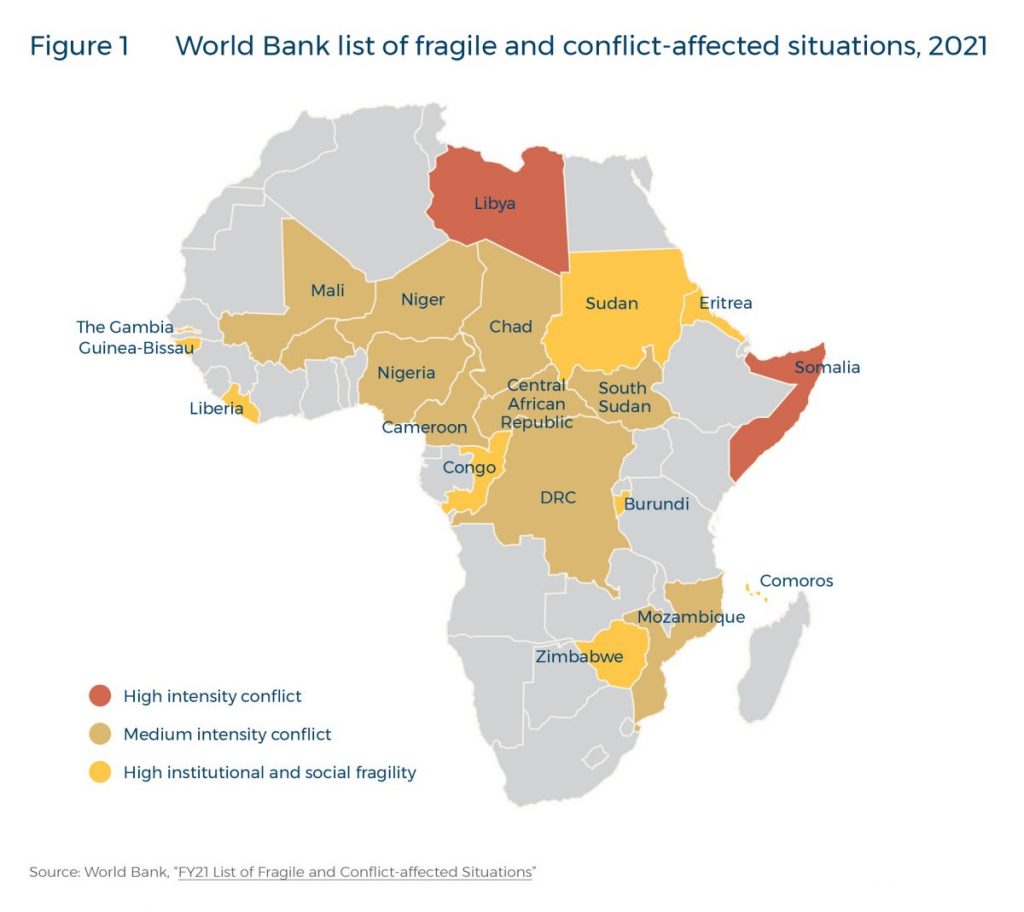

The AUDA-NEPAD’s experiences in the first phase of PIDA implementation revealed that the scarcity of bankable projects – partly owing to the lack of early-stage project preparation capacity at national and regional levels – is a major bottleneck. One challenge that seldom gets enough attention in connection to infrastructure is the complexity of working in conflict and post-conflict environments. Over half of the 39 countries currently classified as fragile and conflict-affected states (FCAS) are in Africa (see Table 1).2World Bank, “FY21 List of Fragile and Conflict-affected Situations”.Given that many PIDA corridors and projects extend across multiple countries, the likelihood that projects will include an FCAS is significant. In light of the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on livelihoods, the risk of conflict in FCAS is currently exacerbated.

Therefore, interrogation of the interactions and impacts of infrastructure on P&S on the continent is warranted. As the AU Infrastructure Fund picks up speed, it is important to understand how PIDA infrastructure policy, planning and implementation can be designed to maximise positive impacts on P&S through legitimised state authority, employment growth and community cohesion. It is also critical to mitigate the risk of conflict hindering the traditional economic benefits of regional infrastructure in FCAS.

This policy brief analyses global and African literature on and best practices in infrastructure development and P&S to see where there are sufficient linkages between infrastructure and P&S in AU and PIDA strategies.

Theory and best practice

Infrastructure and its impact on conflict

Infrastructure has been used to achieve stabilisation objectives in African and other FCAS throughout history, with mixed levels of success. For example, roads and railways are commonly used as tools for state-building (or rebuilding) to provide transportation and communication linkages for the state and military.3Jan Bachmann and Peer Schouten, “Concrete Approaches to Peace: Infrastructure as Peacebuilding”, International Affairs 94, no. 2 (March 1, 2018): 381–398.One of the most prominent recent examples of this is the US military’s use of Quick Impact Projects in Afghanistan. These serve the dual purpose of physically rebuilding the country and re-establishing state authority. On the African continent, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) government and the UN have used the re-establishment of road linkages in eastern DRC as part of a strategy to improve access to state security services and humanitarian support.4Bachmann and Schouten, “Concrete Approaches to Peace”.While the AU’s PIDA projects located in FCAS may not be designed with the primary objective of achieving P&S, they inevitably interact with the regional and/or domestic security context and cannot be divorced from elevated national and local expectations.

Despite numerous examples of infrastructure being used for peacebuilding, empirical research establishing causal linkages between the two is limited. Understandably, the challenging operating conditions in FCAS make empirical findings more difficult to establish.5Stephen Jones and Simon Howarth, “Supporting Infrastructure Development in Fragile and Conflict-Affected States: Learning from Experience” (UK Aid, London, August 2012).A small body of evidence-based literature on infrastructure and P&S broadly distinguishes between two types of infrastructure in relation to impacts on peacebuilding. The first is large-scale public projects, where the primary objective is a physical output that can enhance security and state authority and contribute to overall economic development. The second is smaller-scale infrastructure, often referred to as community-driven development (CDD), where the primary objective is to foster community building and collective ownership of infrastructure.6Bachmann and Schouten, “Concrete Approaches to Peace”.The latter has shown more consistent impacts on P&S by altering collaboration and decision-making practices, although scalability remains a challenge.7Bachmann and Schouten, “Concrete Approaches to Peace”; Jones and Howarth, “Supporting Infrastructure Development”; Jan Bachmann and Peer Schouten, Roads to Peace? The Role of Infrastructure in Fragile and Conflict-Affected States (Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies and UN Office for Project Services, January 2017).For this reason, large-scale public projects often have CDD components to improve outcomes and improve the project sponsor/developer’s ‘social licence to operate’ in communities.

The potential positive impacts of infrastructure on P&S include:

- an increase in state accountability and legitimacy among citizens;

- the creation of employment opportunities;

- physical integration for isolated and vulnerable populations prone to involvement in violent/conflict activities;

- enhancement of military and state defence through transport and communications infrastructure; and

- contribution to positive economic activity (trade, industry, etc.).

At the same time, infrastructure in FCAS can create adverse impacts, by serving as a conduit for corruption and other illegal activities, or increasing contestation and conflict if infrastructure is seen to represent disputed authority or raises land valuations. These dynamics also increase the chances that infrastructure in FCAS will not be completed. Even if infrastructure is physically successful, the expected peacebuilding impacts of legitimising state authority or increasing community cohesion may not be achieved and depend on complex stakeholder interactions and perceptions.8Bachmann and Schouten, Roads to Peace; Bachmann and Schouten, “Concrete Approaches to Peace”; Jones and Howarth, “Supporting Infrastructure Development”; Rubaba Ali et al., “Infrastructure in Conflict-Prone and Fragile Environments: Evidence from the Democratic Republic of Congo” (Policy Research Working Paper 7273, World Bank, Washington DC, 2015).The distinct conditions unique to any FCAS imply that there are limited general conclusions on the nature of such impacts.

FCAS infrastructure policy and planning

Best practice literature on developing conflict-sensitive infrastructure and maximising peacebuilding outcomes converges around a small number of key challenges and recommendations.

First, the dearth of Africa-specific empirical research on the causal impacts of different approaches to infrastructure policy, planning and development highlights the need to prioritise and direct funding and coordination towards evidence-based studies in this area.9Ali et al., “Infrastructure in Conflict-Prone”; Bachmann and Schouten, Roads to Peace; UNOPS, Infrastructure for Peacebuilding (Copenhagen: UNOPS, 2020); Bachmann and Schouten, “Concrete Approaches”Large-scale infrastructure projects are often underpinned by the implied yet false narrative that infrastructure inevitably leads to economic benefit and, therefore, stabilisation and conflict reduction.10Ali et al., “Infrastructure in Conflict-Prone”; Jones and Howarth, “Supporting Infrastructure Development”; UNOPS, Infrastructure for Peacebuilding.The lack of a compiled evidence base comparing the nuance of projects in different sectors, scales, locations and conflict contexts leaves project sponsors unable to anticipate impacts and implement the appropriate conflict-sensitive design. In particular, longitudinal studies, which examine project impacts over time and undertake post-project conflict analyses at subsequent milestones, are lacking.11Bachmann and Schouten, Roads to Peace.Along these lines, there is a need for formalised, multi-stakeholder-driven initiatives (ie, knowledge centres) that collect, collate, analyse and disseminate existing project-level evidence on FCAS infrastructure (ie, project data, empirical studies, conflict analyses, etc.). Such evidence can be used to inform future project planning and commission further research.12Merriam Mashatt, Daniel Long and James Crum, Conflict-Sensitive Approach to Infrastructure Development, Special Report (Washington DC: US Institute of Peace, 2008); Bachmann and Schouten, Roads to Peace; UNOPS, Infrastructure for Peacebuilding.

Second, at the project level, the literature unanimously points to inadequate in-depth conflict assessments being undertaken in FCAS. Conflict assessments should be done as a collaborative effort by experts in infrastructure development, policy, and conflict management, with support from governments and RECs as required. They should map the conflict development cycle (ie, rising tension, confrontation, intermittent violence, sustained violence, ceasefire, agreement, intermittent violence, agreement implementation, decreasing tension) in terms of the likelihood of occurrence and potential severity of impacts at each stage of the infrastructure development cycle (ie, project design, preparation, construction, operation and maintenance) based on the unique context of each project and country.13Mashatt, Long and Crum, Conflict-Sensitive Approach.This requires repeated analyses of the potential for conflict informed by in-depth stakeholder mapping as projects progress. For example, periodic assessments should identify who controls relevant resources and institutions, determine incentives for each stakeholder that might influence their relationship to the proposed infrastructure (relationships might include cooperation, co-optation, or confrontation with infrastructure projects) and anticipate any potential shifts in power among stakeholders.14Mashatt, Long and Crum, Conflict-Sensitive Approach.Often interested stakeholders can extend across borders, especially when conflict is regional in nature (eg, jihadist groups such as al-Shabaab and Boko Haram whose operations extend across countries, or conflicts related to disputed national borders).15Bachmann and Schouten, “Concrete Approaches to Peace”.

Third, it is also important to assess and understand local institutional and technical capacity to receive the target projects and how any capacity deficits or norms and traditions could affect project outcomes or increase the likelihood of co-optation by illicit structures or actors. Conflict assessments require partnerships with trusted local authorities, community leaders and, potentially, intelligence experts. These partnerships will enable the collection of contextual information and intelligence on various community and external interest groups and the adoption of effective negotiating positions. They will also help to gain community trust.16UNOPS, Infrastructure for Peacebuilding.For example, such intelligence can help understand and mitigate organised crime designed to sabotage infrastructure, which is prevalent in FCAS contexts.17Infrastructure project development consultant, interview by Chelsea Markowitz, April 2021.

Fourth, a more thorough understanding of conflict pathways will also better enable the project sponsors to analyse, make allowances for and effectively allocate risk into financing mechanisms, improving the likelihood that projects reach financial close.18Infrastructure project development consultant, interview.Projects in FCAS often do not spend the required time and resources to achieve this level of depth in conflict analysis. They are therefore less able to integrate appropriate mitigatory strategies or contingency plans for negative outcomes. Some public resources that can assist in the development of conflict analyses are:19Mashatt, Long and Crum, Conflict-Sensitive Approach.

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Fragility Framework

- World Bank Conflict Analysis Framework

- US Agency for International Development Conflict Assessment Tools

- International Finance Corporation Performance Standards

- UN Global Compact Business Guide for Conflict Impact Assessment and Risk Management

- The UK Department for International Development’s ‘How-To Note’ on ‘Results in FCAS’

Notably, all of these resources have been developed by Western development partners, underscoring the need for Africa-specific research and conflict assessment tools.

Conflict assessments must then be used to inform project planning and build explicit P&S considerations and procedures into every stage of the project lifecycle. As with any aspect of project development, many of the important P&S provisions must be developed and integrated as early as possible (potentially pre-financial close). This will enable proactive planning and lay a successful, conflict-sensitive foundation. Table 1 provides a (non-exhaustive) list of important P&S considerations for project sponsors and relevant government stakeholders and/or local authorities to build into the project lifecycle. These considerations are either unique to FCAS or pose heightened risks in FCAS.

Infrastructure and peacebuilding within AU architecture

Existing AU peace security and infrastructure linkages

Regional infrastructure development and P&S are both deeply embedded within the AU’s policy architecture. However, these concepts are generally presented as discrete objectives, and potential interrelationships and impacts are seldom accounted for.

Agenda 2063, the AU’s guiding strategy document, advocates both ‘world class infrastructure that criss-crosses Africa’ and ‘communications and infrastructure connectivity’.20AU, Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want (Addis Ababa: AU, 2013).

With regard to P&S, aspiration 4 of Agenda 2063 calls for:21AU, Agenda 2063

A peaceful and secure Africa: strengthening governance, accountability and transparency as a foundation for a peaceful Africa; strengthening mechanisms for securing peace and reconciliation at all levels, as well as addressing emerging threats to Africa’s peace and security; and putting in place strategies for the continent to finance her security needs.

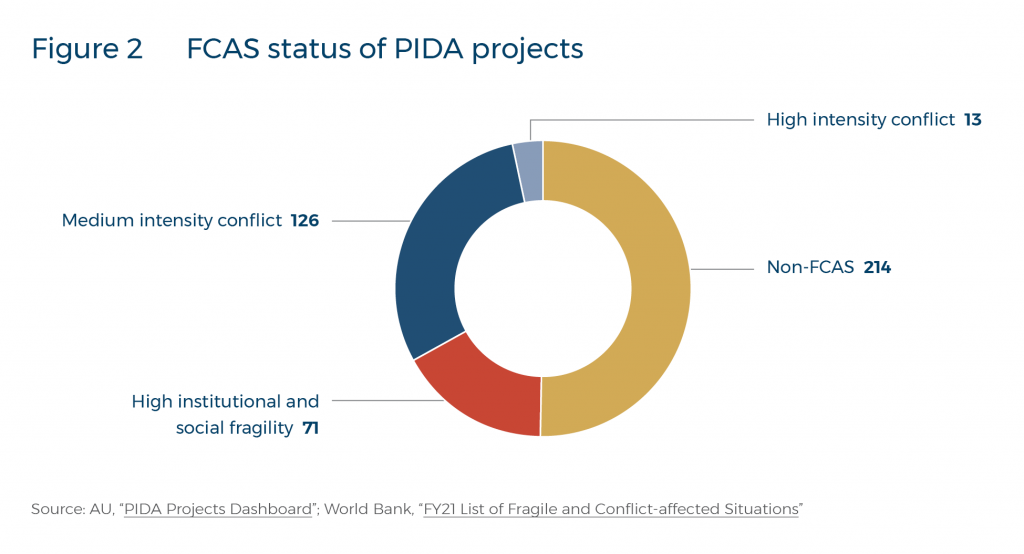

The PIDA strategic framework aims to develop cross-border projects in the energy, transport, information and communications technology, and transboundary water resources sectors. A total of 409 projects are currently included in the PIDA dashboard. As Figure 2 shows, approximately 48% of PIDA projects stretch across at least one country at risk of fragility or conflict. Among these, 17% cross at least one country with high institutional and social fragility, 31% cross a country with medium-intensity conflict, and 3% cross a country with high-intensity conflict.22AU, “PIDA Projects Dashboard”.

Despite this, infrastructure and P&S are not sufficiently represented as integrated and/or interdependent goals within PIDA. The PIDA PAP 2 aims to provide support for 50 projects in pre-project preparation phases, ie, the strategic planning phase.23AU, “The Integrated Corridor Approach: ‘A Holistic Infrastructure Planning Framework to establish PIDA-PAP 2’” (Strategic Note, AU, Addis Ababa, 2020).No provisions are made for a special focus on P&S concerns or specific considerations for projects in FCAS. The PIDA Service Delivery Mechanism (SDM) provides assessments of early-stage project readiness and is the primary technical assistance vehicle to address early-stage project gaps. The SDM does not offer any assessments or capacity-building tools specific to projects in FCAS.24AUDA-NEPAD, interview; AU Development Agency, Service Delivery Mechanism (SDM) for Early-Stage Project Preparation (Addis Ababa: AUDA, 2021).From a review of publicly available PIDA-related documents, the only relevant link is in a document outlining PIDA project risks for a PIDA implementation structure, the AUDA-NEPAD Infrastructure Project Preparation Facility (IPPF). The IPPF document refers to ‘risk of inadequate peace, stability and good governance on the continent’25African Development Bank, NEPAD Infrastructure Project Preparation Facility (IPPF) Special Fund NEPAD-IPPF (Abidjan: AfDB, 2009).and recommends mitigation measures, including an effective AU peacemaking mechanism and the AUDA-NEPAD African Peer Review Mechanism, and intensive stakeholder consultation during project design.

Of the reviewed AU P&S policies and strategies (including the African Peace and Security Architecture [2003], the African Peace and Security Council [PSC] and the Common African Defence and Security Policy [2004], and the AU Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Development Policy [PCRD, 2006]),26AU, Solemn Declaration on a Common African Defence and Security Policy (Addis Ababa: AU, 2000); AU Peace and Security Department, Policy on Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Development (PCRD) (Addis Ababa: AU, 2006).the PCRD gives a slightly more holistic perspective of post-conflict situations. It recognises the need for infrastructure development in postconflict situations in one of its objectives, to 27AU PSD, Policy on Post-Conflict, 19.

[d]evelop physical infrastructure, including transport, communication, energy, water, health and sanitation, as follows: i. Prioritize the rehabilitation and reconstruction of physical infrastructure destroyed during the conflict; and ii. Engage in the planning and execution of infrastructure development in line with the long-term needs of the country.

From this brief overview, the centrality of infrastructure and peacebuilding as isolated objectives within the AU’s development policies and strategies is evident. Further consideration of and planning for the interaction between infrastructure development and P&S are necessary to facilitate successful continental infrastructure development.

Opportunities to build P&S into AU infrastructure development

The findings indicate that a range of opportunities exists for improved integration of P&S considerations and infrastructure financing and development at the continental policy level.

Within the AU, institutionalised coordination platforms can be established between the Peace and Security Department and the Infrastructure and Energy Development Department, with the participation of implementation-focused agencies such as AUDANEPAD and the AU PSC. Coordination can be undertaken through a joint sitting of the Specialised Technical Committee (STC) on Transport, Transcontinental and Interregional Infrastructure, Energy and Tourism and the STC on Defence, Safety and Security. At the same time, a systemic working group could be established between the AUDANEPAD, RECs and the PSC. Through these forums, cross-cutting peace and security and infrastructure policy objectives can be better integrated into policy documents and filtered down to the respective AU strategies, procedures and implementing agencies. The Infrastructure and Energy Development Department can draw on the progress of the Peace and Security Department’s existing policy considerations of the role of infrastructure in driving P&S in post-conflict environments. The PIDA PAP 2 also allows regular and periodic review in its lifespan (2021–2030). Therefore, the PIDA PAP Principles should be reviewed to include a dedicated focus on P&S for projects in FCAS, along with other objectives that are currently included, such as environmental and social impacts, gender sensitivity, job creation, etc.28AU, The Integrated Corridor Approach; AUDA-NEPAD, interviewThese amendments should be developed through joint collaboration among the PSC, the PIDA Steering Committee (comprising the AU Commission, AUDA-NEPAD, RECs, the African Development Bank and the UN Economic Commission for Africa) and, possibly, external expertise.

The growing body of best practice on conflict-sensitive project planning and implementation (see Table 1) can also be institutionalised under the PIDA SDM. One of the SDM’s core services is PIDA Project Diagnostics and Solutions, which aims ‘to assess PIDA Projects that have stalled, identifying bottlenecks and possible solutions for consideration of the project owners, with the implementation of remedial actions as appropriate’.29AUDA, Service Delivery Mechanism (SDM), 5.Along these lines, the SDM offers the ‘PIDA Quality Label’ as a framework to guide project sponsors to achieve excellence in these early project stages and provide technical assistance to projects that score poorly.30AUDA, Service Delivery Mechanism (SDM); AUDA-NEPAD, interviewAs part of the project screening under the PIDA Quality Label (both the Stage 1 ‘Quick Check’ and the Stage 2 ‘Pre-feasibility’), the SDM should offer P&S-specific terms of reference (ToRs) and templates. These can include templates for conflict assessments, ToC, security management, influx management, stakeholder engagement, procurement, and project transition and maintenance specific to FCAS projects, integrating the material considerations from Table 1. These tools should build on and integrate any existing continental work in this space, including the aforementioned NEPAD IPPF recommendations. The OECD is currently working with the AUDA-NEPAD 31Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and African Center for Economic Transformation, Quality Infrastructure in 21st Century Africa: Prioritising, Accelerating and Scaling up in the Context of PIDA (2021-30) (Paris: OECD and ACET, 2020).to provide more standardised guidelines for the continent on feasibility studies, social and environmental impact assessments, community consultations, resettlement, procurement and contracting. Conflict-specific tools can and should be included within this process. The SDM Experts Service Pool, which seeks to provide a broad range of internal and external expertise upon which PIDA project sponsors can draw quickly and cheaply, should include experts from the PSC as well as external experts in the field of conflict-sensitive infrastructure development. While these tools will inevitably increase upfront project preparation costs, they will also create savings during project implementation when costly project obstructions in FCAS are mitigated or avoided.

The AUDA-NEPAD is ideally placed to host a knowledge centre for infrastructure development in FCAS, given PIDA’s championing of numerous continental infrastructure projects. The existing OECD and AUDA-NEPAD collaboration has envisioned a peer learning platform that brings together fragmented continental infrastructure capacity-building initiatives, best practice research and case studies on project preparation for quality infrastructure, and a network of professional expertise to offer centralised knowledge products, training, internships, etc. A P&S sub-theme should be integrated under this structure. The envisioned knowledge centre can act as a repository for existing African regional studies on P&S and infrastructure development, and drive the future agenda for evidence-based project studies in FCAS, hosting dialogues and training to build regional capacity in this space. The P&S component should draw heavily on technical, policy, academic and funding partnerships to ensure a holistic approach to knowledge gathering and dissemination. Development partners currently driving research in this area include the Danish Institute for International Studies, the Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office and the UN Office for Project Services. Cross-departmental coordination with the AU PSC could unlock additional funding, as the PSC has a much larger budget than the AUDA-NEPAD.32AUDA-NEPAD, interview.

Multi-stakeholder, multi-departmental coordination and partnerships are integral to unlocking these opportunities. Effective conflict-sensitive infrastructure development must draw on cohesive high-level policy development, academic evidence-based research, and project planning and implementation expertise.

Conclusion

This policy brief has identified gaps at continental policy level and project level that are hindering the design of conflict-sensitive African infrastructure projects. Through improved interdepartmental policy coordination, the development of specific tools and guidelines for conflict-sensitive PIDA project planning and implementation, and the development of centralised knowledge-sharing platforms, the AU can contribute further to both improved PIDA project completion rates in FCAS and positive spillover effects on peacebuilding. It is crucial to mainstream conflict considerations into policy design and FCAS project development more effectively, with the objective of improving project completion rates and positive spill-over effects on peacebuilding.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Ibrah Wahabou of the AU Development Agency-NEPAD for his support and review of this paper.

SAIIA gratefully acknowledges the support of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) for this publication.