The stakes are high, but it is equally clear that for all the expert opinions on the foolishness of an exit, many people may well vote with their hearts this Thursday, driven by a rhetoric that plays to bygone days of unmitigated national sovereignty and an imperial Britain that ‘ruled the waves’ and was at the centre of the Commonwealth.

Brexit, should that be the result, will have profound consequences for the UK’s status as a financial centre and gateway to the European Union (EU), for its trading relations with the world, and for its global influence.

How might Brexit impact on South Africa?

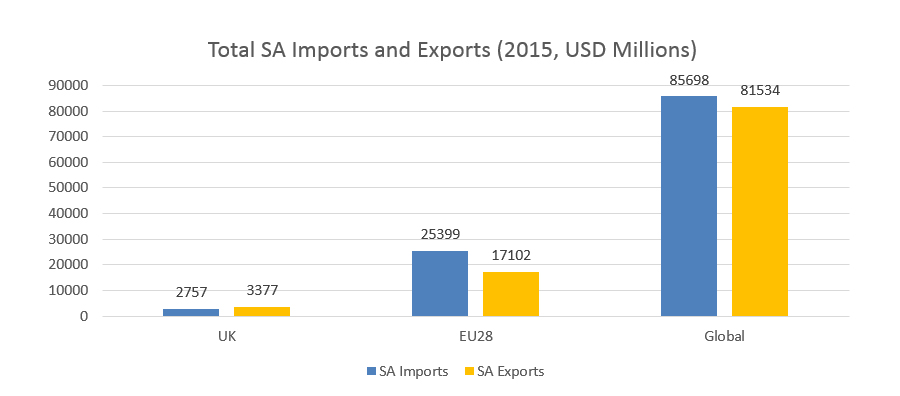

So what do the most recent economic figures tell us about the importance of Britain to the South African economy? In 2015, exports from South Africa to the EU28 totalled more than $17.1 billion, representing some 21% of South Africa’s global exports. Nearly 30% of SA’s imports are sourced from the EU28, but the EU-South Africa trade balance is in Europe’s favour. Overall, EU-South Africa trade amounts to 25% of South Africa’s global trade. The UK comprises 3.7% of South Africa’s global trade.

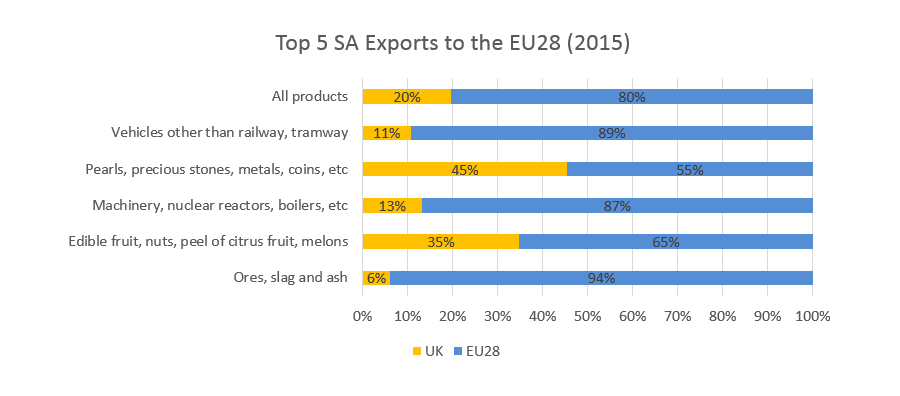

However, the situation is different in the case of South Africa-UK trade, where South Africa records a favourable trade balance. In 2015, the UK received about 20% of all South African goods destined for Europe. Of the top five South Africa exports to the EU, the UK received significant shares of HS71 commodities (almost exclusively platinum) and agricultural goods (notably grapes, citrus, and apples), with 45% and 35% of exports in these commodity groups, respectively.

Not just trade…

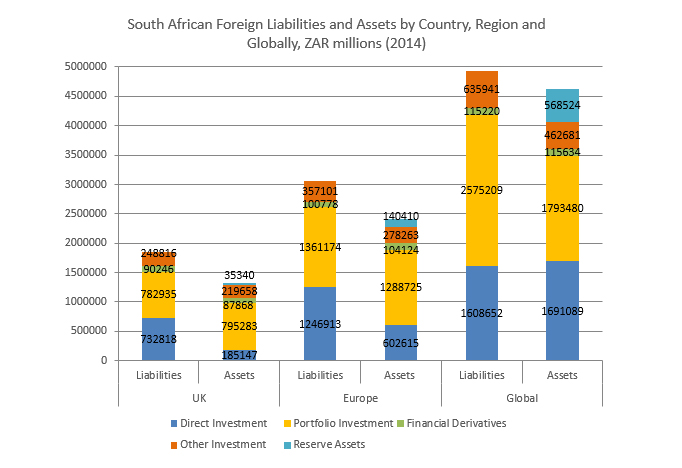

The UK remains both an important source and destination for South African investment, representing 45.6% of direct investment in South Africa and 10.9% of SA’s global direct investments. As of December 2014, the UK’s total direct investments in South Africa were roughly R730 billion, representing nearly 60% of total EU direct investments in South Africa. Equally, more than 30% of South Africa’s direct investments (R185 billion) in the EU were located in the UK.

In terms of portfolio investments, the UK remains a significant partner for South Africa. In 2014, the UK’s portfolio investments in South Africa totalled more than R780 billion (representing more than 57% of EU’s total), while South Africa’s portfolio investments in the EU totalled R1.28 trillion, of which more than 60% were in the UK.

Brexit scenarios

In the event that the UK does vote to exit the EU, Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty provides that the European Treaties shall cease to apply from the date of entry into force of the withdrawal agreement, or failing that, two years after the Member State’s notification to the European Council.

A Brexit would result in the UK no longer benefiting from the FTAs negotiated by the EU with a variety of other countries, including the recently signed Southern African Development Community (SADC)-EU Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA). Trade commitments concluded by the EU and its Member States fall within the EU’s ambit of responsibility, meaning that the commercial aspects of such agreements would no longer be legally binding for Britain and non-EU signatories.

What the UK decides vis-à-vis the EU upon voting for Brexit will also determine the relationship it will need to negotiate (or not) with other parties outside the EU. A working document published by the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) in February this year outlined three possible scenarios in the event of a Brexit:

- Scenario 1: ‘a clean break, “big bang” Brexit’, which would require repealing some 5,000 regulations, directives and decisions relating to the internal market and around 1,100 international treaties between the EU and third countries.

- Scenario 2: Remaining in the EU’s single market and customs union, which would entail joining the European Economic Area (EEA). To join the EEA, the UK would also have to join the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), which has 25 free trade agreements with third countries, including with SACU.

- Scenario 3: Negotiating with the EU and the rest of the world, where the UK would try to get the best possible free trade deal with the EU outside the internal market and also with third countries.

The purpose of this analysis is not to focus on the broader ramifications for the UK of any of these scenarios, but to look specifically at the interplay with scenarios for UK-South African relations.

What consequences for SA trade?

Within the context of South Africa and the Southern African Customs Union (SACU), two issues are of concern: first, South Africa’s trade and business interests in continuing its trading relations with Britain, and second, the impact of a potential Brexit on the new SADC-EU EPA, which is currently awaiting ratification from the South African and European Parliaments respectively.

There are a couple of options available based on the Brexit scenarios outlined in the previous section.

First, if the UK were to decide to join the EEA and EFTA, its trade relations with South Africa would be governed by the existing FTA between EFTA and SACU. This FTA was signed in 2006 and entered into force 1 May 2008. The UK is already a party to EFTA as a Member State of the EU. The main EFTA members are Norway, Lichtenstein, Iceland and Switzerland. In terms of Article 128 of the European Economic Area (EEA) Agreement, EU Member States may apply to become a party to the EEA Agreement. As such, the EEA Agreement permits EEA EFTA participation in its internal market, although with no right to vote. However, the terms and conditions for such participation appear to be subject to a separately negotiated agreement, and the UK would have to re-negotiate its participation in the EFTA as a separate party outside of the EU. Currently, Switzerland has a series of bilateral agreements with the EU (for example, Switzerland is part of the EU single market for goods, but not services); however, given recent stumbling blocks in the EU-Swiss relationship (notably the Swiss vote on restricting movement of labour from the EU, which is yet to be implemented), it is unlikely that the EU would wish to replicate similar trading and political relations with the UK, especially because EU-Swiss relations are subjected to constant negotiations of the EU’s existing body of legislation. In addition, as a separate party to the EEA, Britain might experience increasing difficulty to effectively manage and keep updated separate agreements in a timeous manner, as well as ensuring there are no discrepancies between them – a difficulty currently experienced by the EU in its relations with Switzerland.

Moreover, participation in the EFTA as a separate party outside the EU would require the UK to adopt EU legislation in relevant areas without being able to access and influence the EU decision-making institutions. As such, the UK will forsake the ability to influence decision-making within EU institutions in exchange but it will still be bound, as are the other members of the EEA, by the EU regulatory frameworks; so it will ‘pay but have no say’ – a point that Brexiters have objected to under the current arrangements.

Figure 1 – The EU (blue) and EFTA (green)

Second, if the UK opted to go it alone (scenario 3 above), it could re-negotiate a new free trade agreement (FTA) with South Africa and the other SACU members from scratch (according to the 2002 SACU Agreement all future preferential trade deals involving SACU members have to be negotiated as part of the customs union), with the risk that it might not secure as favourable trade deal as it could have benefited from through its membership of the EU. Currently, trade between the UK and South Africa indicates a fairly equitable trading relationship between the two, and there is clearly an incentive for such negotiations.

If, however, the two-year grace period expired without a FTA or similar trading arrangement in place between South Africa and the UK, it is likely that the MFN (most-favoured-nation) principle would become applicable. This would be unfavourable for both countries compared to a negotiated, bilateral FTA, and might additionally disadvantage the UK as a country whose core strength lies in services. Most FTAs with emerging markets do not provide for trade in services, and South Africa has been historically opposed to including these in negotiations. South Africa and its other SACU partners are also currently negotiating a new generation SACU Treaty, which has been fraught because SA would like to reduce the focus on ‘budget transfers’ to the BLNS states while these would prefer not to lose revenue, given that they are also at a disadvantage from being in a customs union with the ‘regional economic hegemon’. Thus negotiations on the UK front might have an additional barrier in this sense. The question also arises in this scenario, of which trade partnerships the UK decides to prioritise.

What would this mean for the SADC EPA?

The SADC EPA was signed on 10 June. It still has to be ratified by the parliaments of the signatories, including South Africa. Once this has happened it will come into force, but in the event of a Brexit, the UK would not be party to it. The SADC EPA will stand, but the SADC-UK relationship will have to be renegotiated. The UK could have exactly the same provisions in a stand-alone agreement or it gives SACU and the UK the opportunity to negotiate a tailor-made agreement that is different to the EPA. Clearly Mozambique, which is now part of the SADC-EPA would also need to negotiate a separate agreement with the UK in the event.

Capital flows and investments

Apart from trade, however, there are other implications for South Africa in the event of a Brexit. The bilateral investment relationship is quite significant, but in the short term it is unlikely to be affected. The bilateral investment treaty with the UK was terminated in 2013, and South Africa now has a new Protection of Investment Act that will govern foreign investments rather than BITs.

However, a Brexit is likely to result in significant global financial volatility, with not only the pound losing value, but investors also becoming jittery about emerging markets. Capital constraints in the UK as a result of this volatility could also impact on the ability of countries such as South Africa to access financing from British banks. UniCredit estimates that British lenders’ claims on entities in South Africa amount to 178% of SA’s foreign currency reserves.

Such consequences place additional strains on South Africa’s economy at a time when we can least afford it. We have no control over the outcome of the referendum, and there is little we can do to limit the impact on our economy. In the run-up to the referendum, it seems that the ‘remain’ campaign may be gaining ground, which should make South Africans less worried. However, our vulnerability to such external risks should make us even more aware of the importance of creating predictability in our broader policy frameworks, sticking to our belt-tightening, and enabling the private sector to create jobs.