Recommendations

- Encourage SADC members to establish functioning and politically independent PPP units to deliver transparent procurement processes that will attract foreign players.

- The energy, transport and water sectors are very important in a developing region, and the structuring of sustainable projects could yield financially lucrative opportunities to all parties.

- Understanding the political climate in the region is crucial, as it seems that in most countries projects also have to deliver on skills transfer, job creation and the inclusion of local businesses. Encourage openness and transparency regarding the expectations of the host government early in negotiations.

Executive summary

The adoption of public–private partnerships (PPPs) in developed countries could be instructive to developing economies with tight fiscal constraints that want to develop infrastructure with broader social developmental aims. PPPs are an opportunity for the state to benefit from private sector management approaches and technological innovation that provide quality services to the general populace. The benefits of PPPs can be attested to in several jurisdictions. However, there are instances in SADC where relations have been difficult, and the optimal performance of PPPs has not been reached. This policy briefing makes recommendations on how PPPs can be strengthened in SADC based on practical examples in the region.

Introduction

The number of PPPs has grown steadily across the globe. This is attributable to governments’ need to provide life-enhancing basic public services to their citizens. PPPs compare well with some of the unintended externalities of privatisation or the negative outcomes of uncompetitive and incompetent exclusive public ownership.

Origin of PPPs: An overview

The need to fundamentally change the mode of public procurement initially arose from concerns about the level of public debt, which grew enormously during the macroeconomic dislocation of the 1970s and 1980s. It was a time when capital projects public funds. PPPs were particularly useful to supplement the funding deficit. [1] Hence governments invited private investors to form an alliance with them to provide the finance needed to build and maintain public services.

In 1992 the John Major-led government in the UK pioneered the first programme aimed at encouraging PPPs, namely the Private Finance Initiative. This early start resulted in the UK’s having one of the most advanced PPP programmes. Today PPPs are responsible for about 24% of the UK’s public investments. The process was also embraced and adopted by some of Australia’s state governments – especially the state of Victoria.

Worldwide, PPPs have slowly been incorporated into the procurement portfolios of most countries. This has resulted in both positive and negative experiences and some ground-breaking contracting practices and outsourcing arrangements.[2] Early adopter countries are now viewed as being mature and having obtained ‘executional excellence’ (eg, the UK and Australia). They are followed by transient countries, which are still working on ‘effective governance’ (eg, Spain, South Korea and Japan). [3] South Africa started implementing PPPs in 1998 in the road transport sector, so it could be regarded as a relative long-time player in this space. [4] Even larger economies such as China, Germany, Thailand, Brazil, India and the US are latecomers and still working on a ‘long-term commitment’ to PPPs, [5] although most have made tremendous strides to grow this sector in their respective economies.

What are PPPs?

PPPs refer to a legal and/or contractual relationship between a government and a private business venture that is aimed at delivering basic amenities and public services. According to the PPP Unit in South Africa, a PPP is defined as a contract between a public sector institution and a private party, where the private party performs a function that is usually provided by the public sector and/or uses state property in terms of the PPP agreement. Most of the project risk (technical, financial and operational) is transferred to the private party. The public sector pays for a full set of services, including new infrastructure, maintenance and facilities management, through monthly or annual payments.

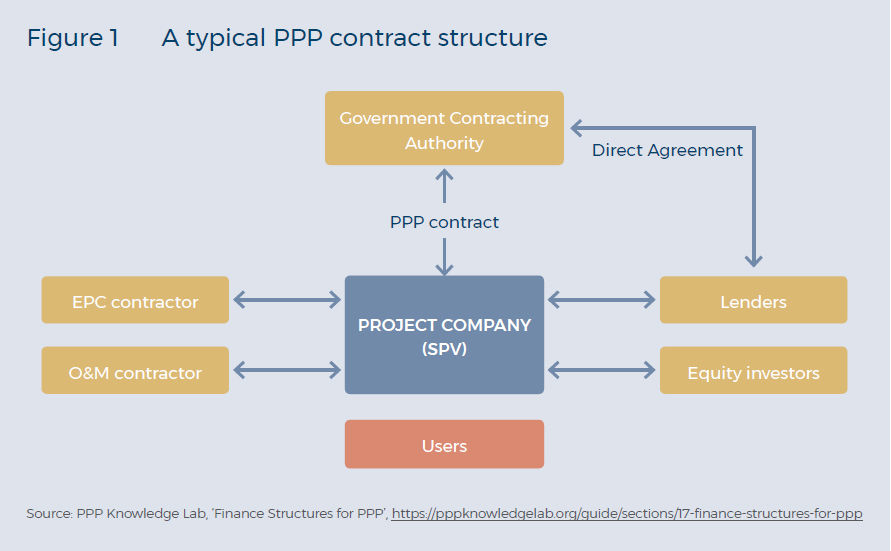

In a traditional government project, the public sector pays for the capital and operating costs and carries the risks of cost overruns and late delivery. [6] A private venture sets up a special company called a ‘special purpose vehicle’ to build, develop, maintain and operate the facility for the specified contracted period. In cases where the government has also invested in the project it is allocated equity. This, however, is not mandatory and is not done in all cases.

The consortium usually comprises a building contractor, a maintenance company and a bank lender(s), if necessary (see Figure 1). The special purpose vehicle has the duty to sign the contract with the government and subcontractors, as well as to build and maintain the project. In the infrastructure sector, more complex arrangements and contracts that guarantee and ensure secure cash flow make PPP projects key candidates for project financing. PPPs are aimed at delivering public service relating to infrastructure, housing, transport, health, education, energy and defence.

Privatisation vs PPPs

Although the principle behind privatisation and PPPs is similar – ie, private party involvement in the delivery of public projects or services – there are distinct differences that public agencies should weigh when considering them.

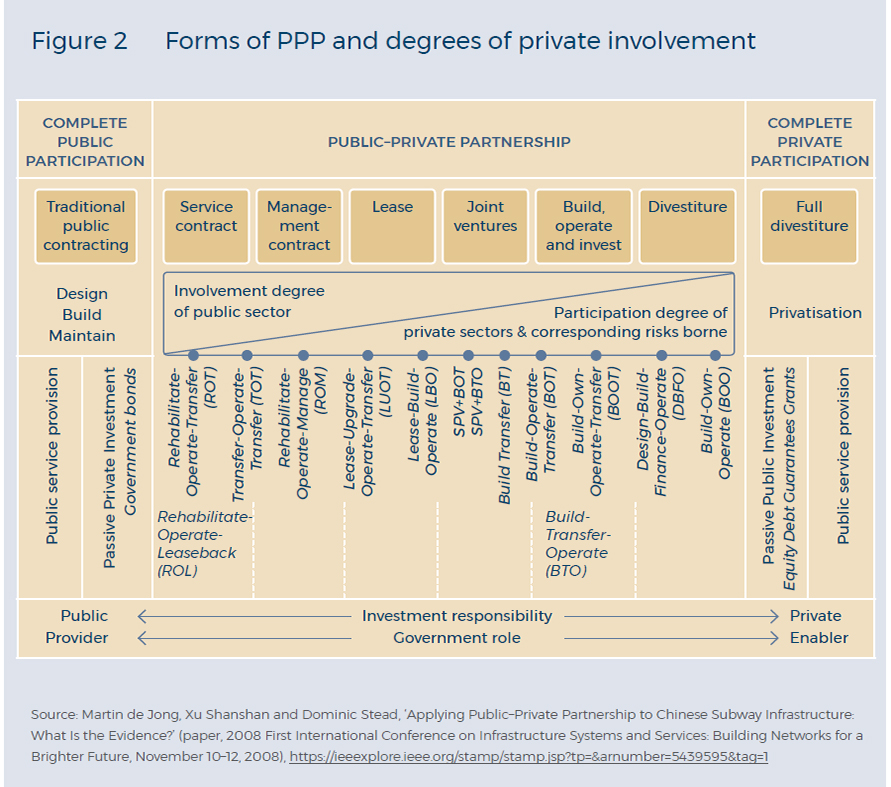

The basic goal of privatisation is the introduction and use of market-based competition by the government using private entities for the delivery of public services or goods. The term ‘privatisation’ most commonly refers to any shift in government activities or functions from a public agency to the private sector. Specifically, privatisation is defined as the economic process of transferring property, such as a building, road or enterprise system that delivers services, from public to private ownership. [7] Privatisation accounts for the process of a public agency transferring such government-owned or -operated commercial enterprises to private sector control and ownership. The California Legislative Analyst Office has described privatisation as the involvement of the private sector in providing goods and services that otherwise might directly be provided by governments. [8] Thus, privatisation occurs when the government sells public assets to the private sector or when the government stops providing a service directly and relies on the private sector to deliver the service. Ownership is the key defining principle of privatisation. Figure 2 shows the fundamental difference between these two routes of public service delivery.

The differences between privatisation and PPPs

Privatisation and PPPs are similar concepts, both rooted in the philosophy that private sector involvement in the delivery of public projects or services can result in operational and fiscal benefits for a public agency. While these terms often are used broadly and interchangeably, there are key differences between them. These differences occur in three primary areas: ownership, structure, and risk. Ownership refers to the party that has, and controls, the rights to or interests in an asset or service enterprise. Structure refers to the resulting contractual arrangements that are used to facilitate privatisation or PPPs. Risk refers to the responsibilities, financial or legal, that are undertaken by the appropriate party – public, private or shared, as conditions of a contract.

- Ownership: A primary distinction between privatisation and PPPs is ownership of the asset (existing or new) or enterprise system that is the subject of the transaction. When a publicly owned asset or enterprise system is privatised, ownership of and responsibility for the asset or enterprise are fully transferred or sold to the private sector. In a PPP, the public agency retains ownership of the asset or enterprise, as well as oversight of the operations and management of the asset, and controls the amount of private involvement. Through a PPP, the public sector sets the parameters and expectations for the partnership and the private sector uses access to capital markets to address the public agency’s needs. If the PPP does not live up to the contractual expectations of the partnership, the public agency can regain complete control of the asset or enterprise system.

- Structure: Another difference between privatisation and PPPs is the structure of the contract that formalises the involvement of the public and private partner after privatisation or the creation of a PPP. With privatisation, once an asset or enterprise is sold, the public agency’s involvement is non-existent, except possibly in a regulatory role. In a PPP, the structure of the agreement is flexible, allowing the public and private partners to determine the level of participation of both partners to specifically address the needs of the public agency, while maintaining public agency ownership. While there are many methods for a public agency to transfer ownership of public assets or services to the private sector, the results are the same: the public sector is no longer involved in owning or managing the public asset or providing the once-public service.

- Risk: Accompanying the asset or enterprise system that is the subject of privatisation or a PPP is the risk associated with the ownership, operation and maintenance of the asset or enterprise for either the remaining useful life of the asset/system or the contract term. Risk is not limited to liability but also includes the assumption of responsibility for conceptual, operational and financial uncertainties that could threaten the goals of privatisation or a PPP. These include design and construction costs, regulatory compliance environmental clearance, performance, and customer satisfaction. An infrastructure project owned and operated by a public agency subjects the agency to 100% of the risks associated with the facility. When an asset or enterprise is privatised, the private owner assumes all risk associated with the asset or enterprise. With a PPP, which has public ownership and private operation, many (but not all) of these risks can be transferred to the private partner. Risk is typically shared, based on the principle that risk should be assigned to the partner that is better equipped to manage that risk or prevent it from occurring, or that is in a better position to recover the costs associated with the risk. Typically, in the development of capital improvement projects, the private partner may prefer to assume risk of a commercial nature that can be appraised and controlled, leaving the residual risks to the public agency. [9] Table 1 lists the risks that are normally adopted by each party.

Reasons for PPPs

The reasons why PPPs are instituted differ from country to country. Below are some of the reasons why state governments embrace PPPs: Firstly, it allows the private sector to influence the quality and speed of delivery of public services. The private sector has over the years been able to maintain an enviable standard in management and delivery. This stands in contrast to most public sector projects, which are often mired in debt and mismanagement. [10] Some of the main reasons public projects fail are:

- Technical issues: These account for most project cost overruns and schedule delays. Common technical glitches leading to project overruns are inaccurate forecasting and cost estimating techniques, insufficient data and poor judgments arising from insufficient experience in project cost forecasting and estimation, as well as the general impossibility to predict the future.[11]

- Optimism bias: Estimation bias stems from being overly optimistic about the prospects of a project in terms of cost and time. Flyvbjerg [12] suggests this is a more plausible cause of cost overruns and project time delays than technical glitches, arguing that political and competitive pressures on projects incentivise project promoters to de-emphasise costs and risks while overemphasising project prospects to get approval from decision makers.

- Strategic deception and misrepresentation issues: Project cost overruns and schedule delays may stem from a deliberate misrepresentation of facts by project planners and promoters with the intent to mislead. Actual project cost/benefit projections and time schedules can deliberately be misrepresented by project planners and promoters in a bid to win the contract award and to start construction as soon as possible. [13]

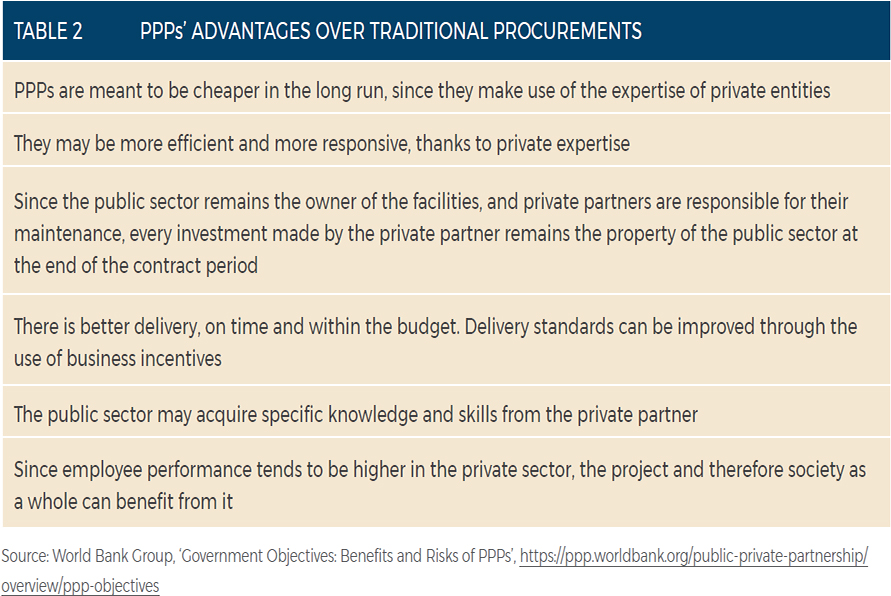

Secondly, it ameliorates budget constraints. Many debt-ridden countries see PPPs as a viable option to provide public services while channelling their constrained budgets to other projects.

Thirdly, it enables access to private sector know-how. The private sector is often more advanced than the public sector in keeping abreast with the latest technical advances and expertise. This is an essential trait that allows it to maximise its competitive advantage.

Fourthly, it enables the transparent treatment of PPP finances. Public sector financial management records are sometimes difficult to penetrate. PPPs, in contrast, adhere to private sector accounting standards, which enables shareholders to ensure best use of

funding.

Fifthly, incentives are offered to aid private sector involvement, such as tax relief. At the end of the day the economic ripple effects from improved service delivery by the private sector outweighs the tax concessions.

Finally, the private sector is continuously innovating. The invention and introduction of new technologies by the private sector can support more effective public services. Table 2 listssome benefits that are brought about by adopting PPPs.

Africa’s PPP landscape

Infrastructure development is essential for achieving sustainable, socio-economic development across Africa. Building resilient infrastructure and promoting sustainable industrialisation was first recognised in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) as an important requirement for improving living standards. Following from the MDGs, Goal 9 of the Sustainable Development Goals recognises the importance of building resilient infrastructure, promoting inclusive and sustainable industrialisation and fostering innovation. Addressing infrastructural backlogs and developing new public assets such as transportation, healthcare and electricity are essential to Africa’s long-term development, especially in rural areas, which often face high upfront costs in infrastructure development. [14] The World Bank estimates that poor infrastructure in sub-Saharan Africa reduces economic growth by 2% and business productivity by as much as 40%, while inadequate infrastructure services can cost twice as much in sub-Saharan Africa than the rest of the world. [15] Infrastructure development and industrialisation is recognised and prioritised by the AU through its Agenda 2063 and its Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA). PIDA’s ambitious efforts focus on building cross-border infrastructure that will ultimately increase regional infrastructure integration, address poverty levels, reduce income inequalities and promote socio-economic development. Its 51 programmes, as identified in the PIDA Priority Action Plan, are spread across the energy, transport, crossborder water infrastructure, and information and communications technology (ICT) sectors. PPPs have the potential to play a real and significant role in helping African countries to meet their infrastructure targets and reduce poverty levels. Globally, PPPs contribute 15–20% of total infrastructure investment,16 and the World Bank’s support of PPPprogrammes as tools to spur growth and combat poverty increased from $0.9 billion in 2002 to $2 billion in 2012.

In Africa, the African Development Bank has supported the uptake of PPPs as an alternative means of financing infrastructure development. Electricity, ICT and ports are the top three sectors for PPPs in sub-Saharan Africa. [17] Although PPPs are not a ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution to addressing Africa’s infrastructure deficit, it is important to understand the kind of contributions that PPPs, if properly implemented, can make, and the business case that can be made for the private sector to enhance its participation in infrastructure projects.

The SADC Development Finance Resource Centre was established in 2003 as a subsidiary institution and currently has 41 members from all 15 SADC countries. It commissioned a PPP case study report to examine private sector experiences of PPPs in SADC. A SADC PPP Network was subsequently launched in February 2011 in South Africa as a platform for promoting PPP policy harmonisation in the region, exchanging information and experiences, and developing capacity in PPPs. [18] SADC is a mixed bag in terms of PPP preparedness with the necessary administrative maturity. South Africa is the obvious leader, while several countries at this point do not have a PPP unit.

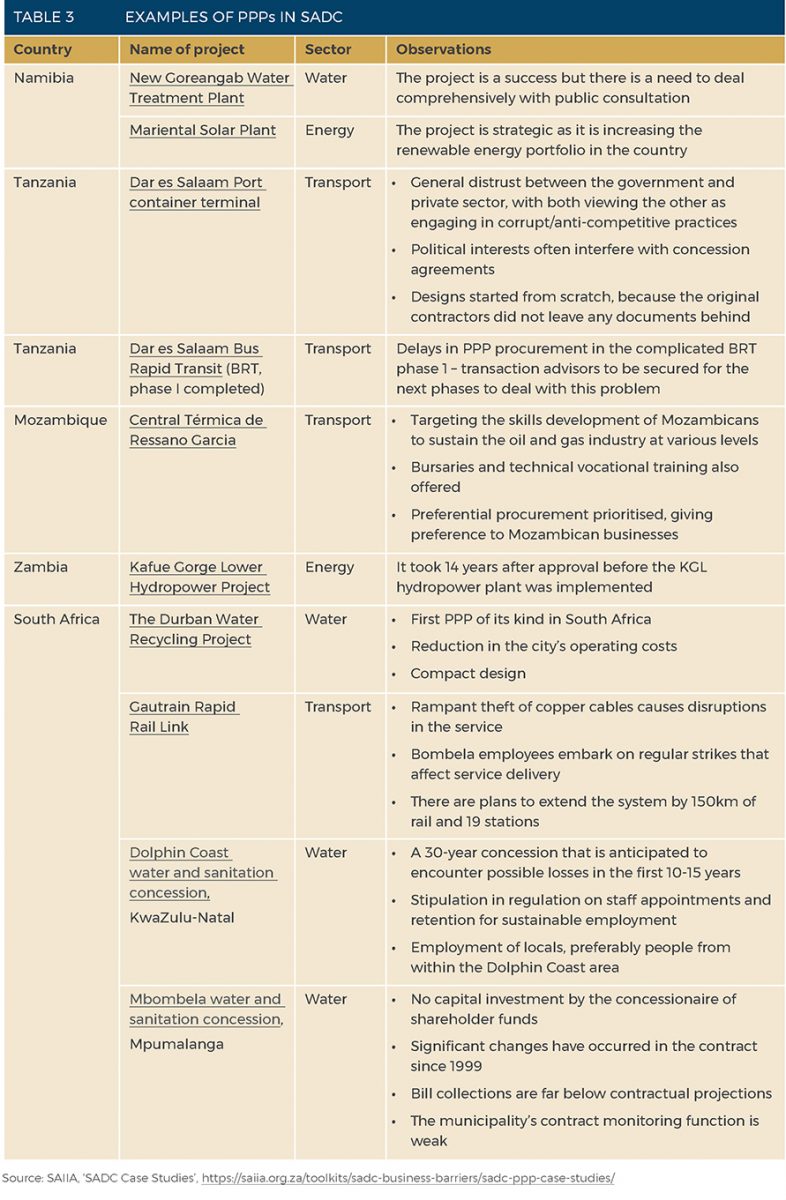

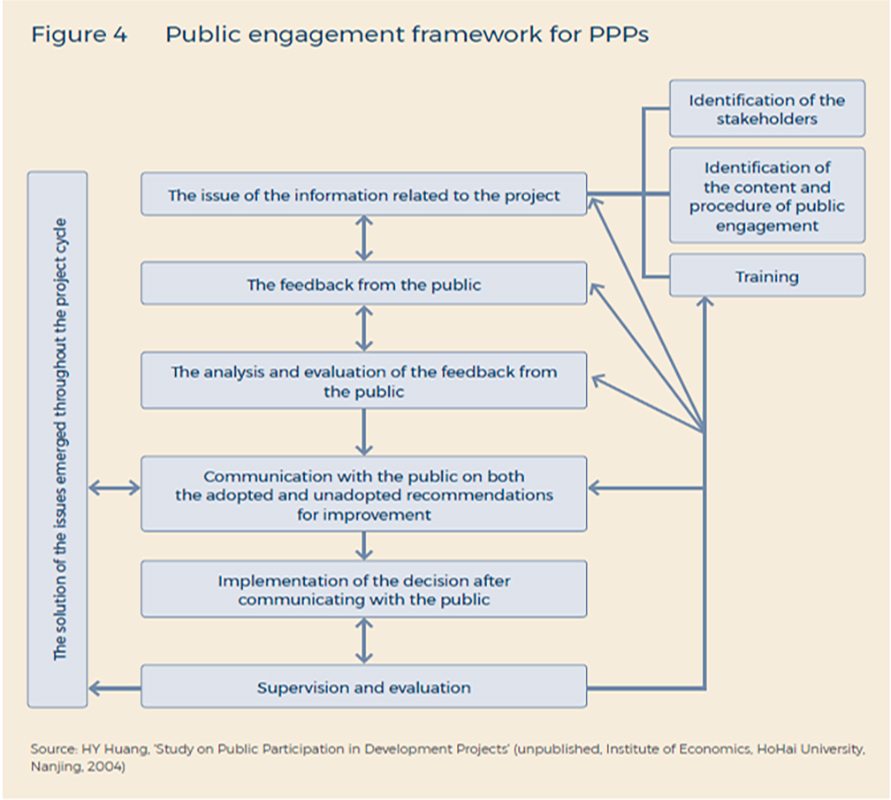

PPPs are implemented in different contexts in the SADC region where knowledge of the political terrain, landscape and contextual nuances can further their success. Table 3 shows that public consultation protocols still have to be strengthened in order to get the necessary buy-in from the general public.

Practical recommendations would thus be:

- changing legislation in countries that are still lagging behind so that public engagement becomes a mandatory process during the whole project cycle;

- establishing guidelines to cover the scope and procedure of, and approach to, participation;

- encouraging more people to participate by adopting diversified methods to garner public opinions, such as online surveys, public forums, face-to-face interviews, etc.; and

- paying more attention to special groups. [20]

Figure 4 proposes a public engagement framework that could be used for PPPs.

It is also imperative to do due diligence on external prospective partners, as this will lessen both information asymmetry and distrust between the parties. Proper due diligence will reduce incidents where contractors abandon projects, as their track records would have been scrutinised beforehand. One way of doing this would be involving transaction advisors early in the process, something which does not appear to be the case in some countries in SADC. Furthermore, it is crucial that PPP units are given enough space and freedom to do their work efficiently. The observed political interference in some cases could lead to a situation where a wrong or non-sustainable decision is made.

Important considerations hampering the uptake of PPPs in SADC countries

- Equity in PPPs: The shift towards ‘smaller government’ tends to apportion a greater share of economic activity to the private sector. A typical way of reducing costs has been to outsource activities once carried out by government, particularly in relation to infrastructure. However, this type of arrangement often perversely results in the PPP’s having the characteristics of a natural monopoly. [21] Many of these ventures require private equity capital. Even with the serious need for infrastructure investment and abundant funding, emerging markets by and large still face challenges owing to the discrepancies between investor needs for profit maximisation and immature PPP frameworks. Investors have requirements that they want met, which could be why there is a problem with equity in some SADC countries.

- Government guarantees: Energy and other projects in Africa are often hard to finance and, to reassure potential lenders, their legal structure requires more security instruments than in developed countries. To address this requirement, independent

power producers, for instance, will commonly seek a sovereign guarantee by the host government. Some countries are reluctant to issue these because of the aversion to contingent liabilities. This in turn impedes the roll-out of PPPs. - Insurance: There is significant foreign ownership of insurers in SADC, although this varies greatly from country to country. A total of 19% of insurers in South Africa are majority foreign owned, 20% in Mauritius and Zimbabwe, 73% in Mozambique and Tanzania, and 100% in Swaziland. The impact of foreign ownership is even greater when considering premium volumes. In six SADC countries more than 20% of foreign-owned insurers are majority owned by entities in other SADC countries, and in three countries this rises to more than 50%. Cross-border ownership within SADC is therefore already a significant factor. This means that anyone who wants to venture into the SADC market is likely to use South African insurance resources, potentially in partnership with international players. South Africa has a good record with credible insurers so the region benefits from having such a strong neighbour.

- PPPs and the debt trap: One of the big challenges of the rising debt phenomenon in Africa is that if a country is heavily indebted it might divert resources that could be used to drive developmental programmes to service the debt. Even if a country has debt, some programmes are still imperative, and substantial investment requirements cannot be met by debt alone. This is where PPPs can make a valuable contribution. [22] However, the cost to a government of using PPPs to invest is usually higher than if it had simply borrowed the money itself. Research commissioned by the European Parliament in 2014 suggests that PPPs are the most expensive way for governments to invest in infrastructure, ultimately costing more than double than financing raised through bank loans or bond issuance. [23]

PPPs with government guarantees are the real culprits. In availability PPPs, for instance, the government pays for the fact that the facility is available irrespective of whether it is fully used or not. One example is where a set annual amount is paid for providing a hospital as a facility. Other costs could be contingent liabilities, where the government guarantees payments if revenues do not meet a certain level, for instance by topping up payments to an electricity producer if revenues have not met the contracted amount or if a debt is defaulted on. These arrangements have the same financial burden on the government as when it is borrowing directly, but the payment obligations are not included in the state’s debt figures. This way the debt payments are usually hidden from public view. Their total cost to the government should be calculated clearly and transparently to determine if they offer value for money. If there is inadequate transparency it means there is a likelihood of PPPs’ being even more expensive than the traditional approach. [24] This reinforces the need for well-resourced and competently managed PPP units in this region.

Footnotes

[1] Martin de Jong et al., ‘Introducing Public–Private Partnerships for Metropolitan Subways in China: What Is the Evidence?’, Journal of Transport Geography 18 (2010): 301–313.

[2] Sock-Yong Phang, ‘Urban Rail Transit PPPs: Survey and Risk Assessment of Recent Strategies’, Transport Policy 14, no. 3 (2007): 214–231.

[3] Raymond E. Levitt, W.R. Scott and Michael J. Garvin, Introduction: PPPs – theoretical challenges and directions forward in Raymond E. Levitt, W.R. Scott and Michael J. Garvin (eds), Public–Private Partnerships for Infrastructure Development (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019), 1–14.

[4] Nathanael Bruchez, ‘Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) in South Africa’ (MA Thesis, University of Bern, 2019).

[5] Levitt, Scott and Garvin, Introduction: PPPs – theoretical challenges, 1–14.

[6] Government of the Republic of South Africa, National Treasury, ‘Public–Private Partnerships’, http://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/national%20budget/2017/review/Annexure %20E.pdf.

[7] Bent Flyvbjerg, ‘Policy and Planning for Large Infrastructure Projects: Problems, Causes, Cures’, Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 34, no. 4 (2007): 578–597.

[8] California Legislative Analyst Office, ‘LAO Analysis of the 1996-97 Budget Bill, P&I Part V-6 Privatization in California State Government’ (Sacramento: California Legislative Analyst Office, 1996).

[9] California Debt & Investment Advisory Commission, ‘Privatization vs. Public–Private Partnerships: A Comparative Analysis’, August

2007, https://www.treasurer.ca.gov/cdiac/publications/privatization.pdf.

[10] Paul Terna Gbahabo and Oluseye Samuel Ajuwon, ‘Effects of Project Cost Overruns and Schedule Delays in Sub-Saharan Africa’, European Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 3 (2017): 46–58.

[11] Matii Siemiatycki, ‘Cost Overruns on Infrastructure Projects: Patterns, Causes, and Cures’ (IMFG Perspectives Paper, Toronto: University of Toronto), 11.

[12] Flyvbjerg, ‘Policy and Planning for Large Infrastructure Projects’.

[13] Gbahabo and Ajuwon, ‘Effects of Project Cost Overruns’, 46–58.

[14] Lesley Wentworth and Catherine Grant Makokera, ‘Private Sector Participation in Infrastructure for Development’, South African Journal of International Affairs 22, no. 3 (2015).

[15] Jamal Saghir, ‘Sustainable Infrastructure Development in sub-Saharan Africa: A View from the Ground’ (Policy Briefing, Institute for the Study of International Development, Montreal, 2017).

[16] María José Romero, ‘What Lies Beneath? A Critical Assessment of PPPs and Their Impact on Sustainable Development’ (paper, Eurodad, Brussels, 2015).

[17] World Bank, ‘Private Participation in Infrastructure Database’, http://ppi.worldbank.org/snapshots/region/sub-saharan-Africa.

[18] South African Institute for International Affairs, ‘SADC PPP Case Studies: SADC Business Barriers’, (Johannesburg, 2013). https://saiia. org.za/toolkits/sadc-business-barriers/sadc-ppp-case-studies/.

[19] Terry HY Li, S Thomas Ng and Kelwin KW Wong, ‘A Framework of Public Engagement for PPP Projects in China’ (paper, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 2009).

[20] Li, Ng and Wong, A Framework for Public Engagement.

[21] Kevin Davis, ‘PPPS and Infrastructure Investment’, The Australian Economic Review 38 (2005): 439–444.

[22] Anzetse Were, ‘Private Partnerships Will Lead to Reduced Public Debt’, Business Daily, April 9, 2017, https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/analysis/Private-partnerships-lead-reduced-public-debt/539548-3883458-119y2df/index.html.

[23] Were, Private Partnerships.