Despite being derailed at multiple points on a long, uneven journey, recent developments around Ghana’s nuclear plans provide hope and lessons for the rest of Africa.

Ghana has experienced recurring periods of unstable electricity supply in 1983, 1997-1998; 2003; 2006-2007 and again from 2011-2017. Domestic natural gas and oil reserves provide some relief, but projections indicate that these will dry up by 2045. The National Electrification Scheme (NES) aimed for universal electricity access by 2020; however this is more realistically attainable by 2022.

Access to electricity in Ghana is fairly widespread with the electricity access rate at 85% in 2019. However, problems with the country’s conventional sources of electricity signal that the time is right for Ghana to pursue its nuclear aspirations alongside other renewable energy generation options to achieve the twin goals of economic development and consistent electricity supply.

By 2057, Ghana hopes to have a highly industrialised economy. It has singled out nuclear power as a key vehicle of development. Ghana’s nuclear ambitions started with the establishment of the Kwabenya Nuclear Reactor Project in 1961. Derailed by consecutive military coups d’état, the project remains uncompleted. Commitment to the establishment of a functioning, effective nuclear power programme from government has also been inconsistent.

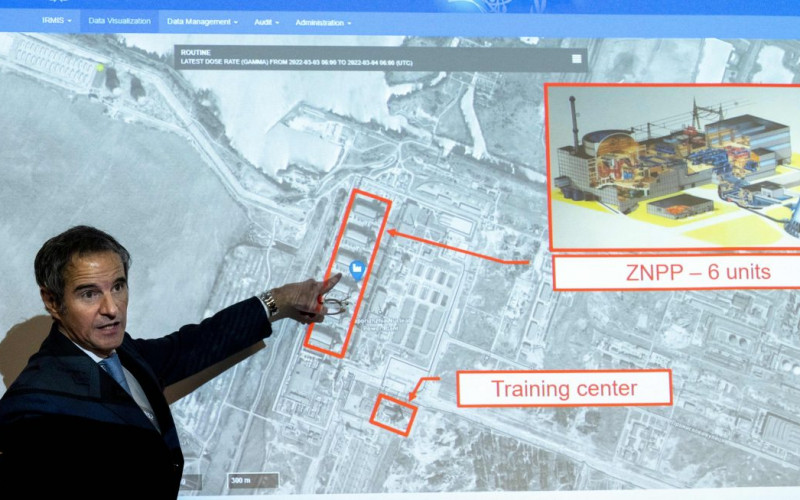

Yet recent developments provide hope. The return of nuclear energy to the country’s development agenda is accelerated by the need for a stable electricity supply. In 2015 the Ghana Atomic Energy Commission (GAEC) called on the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to carry out a ‘Phase 1 Integrated Nuclear Infrastructure Review Mission (INIR)’ in the country.

INIR evaluations represent an important step in the establishment of a nuclear energy programme in any country and ensure that expert decisions guide these highly technical projects. INIR evaluations are based on the IAEA’s ‘Milestones in the Development of a National Infrastructure for Nuclear Power‘ document, which outlines three development phases of a nuclear power programme.

First phase reviews assess the readiness of a country to embark on the road to nuclear power and take place at the decision-making stage. Second phase reviews follow directly from the first and entail putting into place concrete actions after the decision to go nuclear has been taken. In the final phase, the nuclear power programme is implemented.

Not long after the GAEC initiated contact with the IAEA, the Ghana Nuclear Power Programme Organisation (GNPPO), which is responsible for overseeing the programme, provided a self-evaluation report. Acting on both the initial communication as well as the report submitted by the GNPPO, the IAEA sent an expert team to Ghana in January 2017 in order to carry out the INIR Mission.

The team determined that Ghana had sufficiently progressed in order to begin preparation for the second phase of the project and another Review Mission. Before progressing to this next phase; however, the evaluation team suggested prioritising further research and bolstering of Ghana’s legal framework.

Establishing a nuclear power project seems logical for a country that is no stranger to the peaceful application of nuclear technology. Ghana has successfully operated a 30kW nuclear research reactor for more than two decades. The Ghana Research Reactor-1 (GHARR-1) is one of 12 research reactors on the African continent and plays a vital role in the education and training of personnel to oversee its emerging nuclear energy programme. GHARR-1 is also relied on for research , particularly the treatment of nuclear waste and environmental safety, and irradiation projects. Ghana also relies on nuclear technology for administering radiotherapy and other nuclear medicine applications.

The energy supply situation in the rest of Africa is not very different. Power outages are regular occurrences in much of Africa and according to the IAEA, more than half of the population of sub-Saharan Africa remains disconnected from the grid. Nuclear power represents an alternative and reliable source of electricity.

Excluding South Africa, where nuclear power is already established, the IAEA notes that nearly one third of the countries that have approached it for assistance in establishing a nuclear power programme are African. Apart from Ghana, these include Egypt, Morocco, Kenya, Niger, Nigeria and Sudan. According to the IAEA, the nuclear option is also under consideration in Algeria and Tunisia as well as Uganda and Zambia.

If the road to nuclear energy in Ghana is anything to go by, it is a telling example to other African countries of the commitment necessary, as well as the importance of political stability and political will in implementing a project that holds vast potential for economic and human development.

This piece draws on research conducted by Hubert Foy and Isabel Bosman for an upcoming SAIIA Special Report on the peaceful use of nuclear energy in Ghana.