In January this year, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moved its Doomsday Clock to 90 seconds to midnight, an indication that humanity is closer than ever to destroying itself. The existential threats it identifies also impact the people of Africa.

The Bulletin, founded by a group of scientists including Albert Einstein, introduced the Doomsday Clock in 1947, when it was set at seven minutes to midnight. Using the imagery of midnight on a clock-face as representing global catastrophe, the group analyses threats to humanity and illustrates its conclusions every year by estimating how close we are to that point in time.

The group’s analysis is normally based on an evaluation of the effects of climate change, disruptive technologies and nuclear threats. This year, however, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, now entering its second year, was listed as a key motivator for moving the Doomsday Clock forward. In addition, biological threats were also considered.

All of these threats, both those previously assessed and the new threats identified this year, have an impact on Africa.

According to the most recent State of the Climate in Africa report, issued in 2021, the continent has recorded a rapid rise in temperature over the last 10 years. This is contributing to rising sea levels in coastal areas and food insecurity due to reduced agricultural production. In addition, increased water scarcity is impacting the lives of some 250 million people in Africa and is likely to displace around 700 million people by 2030.

The Bulletin reported that globally, adverse weather conditions continued throughout 2022 but this time they were “more evidently attributable to climate change”. This resulted in severe droughts in some parts of Africa while others, notably western and southern Africa, have had to grapple with heavy rainfall and flooding.

The Ukraine war impacted climate-related food insecurity in Africa, as well as the continent’s economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) observed promising recovery rates in Africa in the second half of 2021, informing its prediction for GDP growth of 4.5 percent for 2022. However, the war, and its impacts on trade and global food and crude oil prices, saw the IMF lowering its 2022 forecast to 3.8 percent.

Crude oil and food prices – especially of wheat and sunflower oil – increased drastically after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Crude oil prices rose to as much as U.S.$120 a barrel but have since come down, to just under $83 in early December last year.

The African Development Bank reported in April 2022 that wheat prices in Africa had increased by as much as 60%. Many economies that depended on wheat imports from both Ukraine and Russia were adversely affected, although the Food and Agriculture Organisation has reported that by January this year global wheat prices had come down by 17.9% since their peak in March 2022.

The war also influenced agricultural production and construction within Africa, since it disrupted access to fertilisers, iron ore and steel – products that many African states import from Russia and Ukraine. For example, in Cameroon, Africa’s biggest importer of fertilisers from Russia, the price of this commodity had increased by more than 50% by August last year. Many farmers could no longer afford fertiliser and had to reduce crop production. Farmers across the continent shared this experience.

The food security risks demonstrated by the war are galvanising thinking about exploring “more strategic policies and programmes”, with experts urging states to turn to “alternative localised, regional, and intra-regional food systems”.

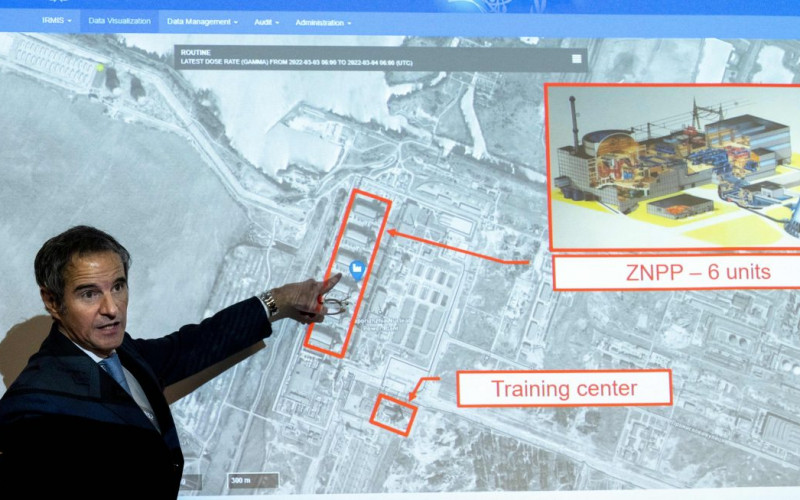

The Ukraine conflict has also raised the spectre of nuclear war. As the world’s largest Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone and a well-known and respected proponent of a world free of nuclear weapons, Africa has an important role to play in ensuring that nuclear weapons are never used again.

South Africa recently hosted a regional seminar promoting the United Nations treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). The momentum required to realise the ideals of the treaty will come primarily from the non-nuclear weapons states of the Global South, and African states can play a leading role in lobbying for this. Already, 33 African states have signed the treaty, while 15 are states parties.

Finally, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists this year identified as a significant biological threat a phenomenon familiar to Africa: zoonotic diseases, which can spread between animals and people. COVID-19 has demonstrated both the disastrous consequences such diseases can have and the need to invest in public healthcare, early warning systems and the development of life-saving vaccines. The World Health Organisation reported last year that the prevalence of zoonotic diseases in Africa has increased by 63% over the last decade. The UN body reports that their rise can be linked to increased urbanisation and the expansion of roads and other forms of transport.

However, African states have been pro-active in combatting zoonotic diseases. Africa is part of the Veterinary Diagnostics Laboratory (VETLAB) Network established in 2012 by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in partnership with the Food and Agriculture Organisation. The network includes 71 laboratories, 45 of which are in Africa.

The network has played a vital role in detecting and managing outbreaks of Ebola, avian influenza, African swine fever and even COVID-19, and allows experts to share data and knowledge. In addition, the continent has also played a key role in the IAEA’s Zoonotic Disease Integrated Action (ZODIAC) initiative, established in June 2020. Through the ZODIAC initiative, the IAEA aims to assist countries in preventing “pandemics caused by bacteria, parasites, fungi or viruses that originate in animals and can be transmitted to humans.”

In his annual statement to the UN General Assembly, Secretary-General António Guterres referred to the Doomsday Clock as “a global alarm clock” and called leaders to action. Empty commitments that remain on paper are not going to cut it in a world threatened predominantly by human-made technologies and developments. Leaders of African states should heed the Clock’s warning and implement concrete actions that will ensure a climate-resilient, peaceful and sustainable future for the continent and its people. Doing so will require substantial introspection and a determination to address Africa’s most pressing internal challenges, while carefully balancing external partnerships.